In the mid-19th century, a 12-year-old boy from rural China named Lim Lip Hong immigrated to the United States, seeking opportunity. He found work building the Central Pacific Railroad – the westernmost portion of the Transcontinental Railroad. Construction on the railroad was overseen by the Big Four, who included Leland Stanford. Today, Lim’s great-great-great-grandson Michael Solorio is an undergraduate at Stanford.

It was about 10 years ago that Solorio first learned about his family’s connection to the Transcontinental Railroad. “My mom and grandma were researching our ancestry, and they traced one line all the way back to Lim Lip Hong,” Solorio said.

Over the coming years, Solorio would learn more about Lim’s life, his family’s deep roots in California and his connection to the university from which he’ll graduate next year.

That connection is discussed in the upcoming book Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, by Gordon Chang, a historian in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. The book is part of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, which will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in an event April 11.

Coming to America

Lim was born in a small village in Guangdong Province, China, in 1843, when the country was reeling from an economic collapse and the First Opium War. In 1855, he was asked to travel to the United States to work and send money home to support his family. So Lim boarded a boat, traveled across the Pacific and arrived in San Francisco, initially finding work washing clothes, building stone fences and digging canals in the Sacramento River delta.

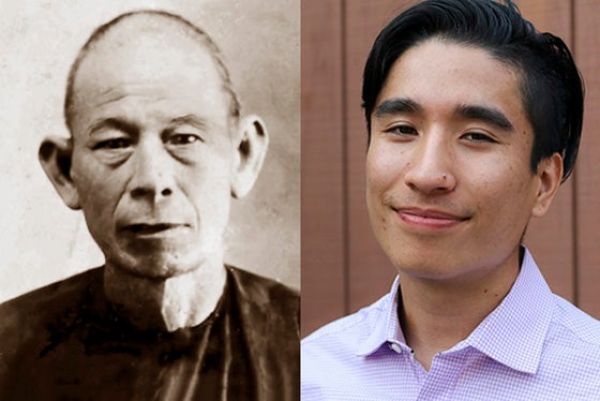

Lim Lip Hong, left, is the great-great-great-grandfather of Stanford student Michael Solorio, right. (Image credit: Hong: Courtesy Glenn Robert Lym; Solorio: Courtesy Michael Solorio)

At the time, California had already drawn scores of Chinese immigrants who hoped to strike it rich in the Gold Rush. When the Gold Rush ended, many of those immigrants found work building the Central Pacific Railroad.

A documentary produced by one of Lim’s descendants explains that Lim was among the first Chinese people hired for the project. He was not a laborer, but rather a crew head, responsible for supervising workers and recruiting others from across the West and even from his hometown in China. After the rails were laid, most Chinese workers were let go, but Lim remained employed by the project’s leaders until the railroad line’s completion at Promontory Summit in Utah on May 10, 1869 – 150 years ago. Lim was just 26.

After more than a decade working on the railroad, Lim left Utah, but did not settle down as a laborer. Instead, his descendants believe he traveled around the West making his living as a merchant.

Lim was 6 feet tall, slender with large hands and ears. He was a skilled horseman who dressed like a cowboy and frequented the Bucket of Blood Saloon in Virginia City, Nevada, which is still open today. Around that time, he fathered several children with a Native American woman, but left them to travel back to California.

He returned to San Francisco in the 1870s, when intense anti-Chinese discrimination was sweeping the West. There he met his wife, Chan Shee, a 16-year-old native of China who came to San Francisco to work as household help for a doctor in Chinatown. A shrewd businessman, Lim had the money and negotiating skills to pay for her release from work, and in 1879 the couple married. Rather than stay in Chinatown, as most Chinese people in San Francisco did at the time, the couple settled on a ranch in Potrero Hill, where they raised seven children, some of whom pursued civic and business careers in and around San Francisco.

Tracing family roots

Today many of Lim’s descendants remain in the Bay Area or elsewhere in California. Solorio grew up in Santa Ana and was born to a Chinese mother and a Mexican immigrant father. He met fellow descendants several years ago at a gathering among those who traced their connections through a family tree. Wanting to further explore his Chinese roots, Solorio traveled to China in 2017 to visit Lim’s hometown.

“It was really humbling to visit the village,” Solorio said. Located in a rural area far from any city, the village is now abandoned. Solorio was able to see Lim’s childhood home, but all that remained of the tiny two-room house were a few walls covered in foliage.

“It made me realize that I’ve come so far, and it’s because of the work of all the people before me, like my parents and parents’ parents, all the way back to Lim Lip Hong,” Solorio said. He’s currently in his junior year and is majoring in materials science and engineering.

Solorio said he’s grateful to be here, and that the knowledge of his family’s history and the contributions of Chinese immigrants like Lim have given him a deeper appreciation for what it means to live in this country. “To know that we’ve been doing a lot of work for the United States makes me feel very much American and deserving of the title,” he said.