When explorers venture into the great unknown of outer space, they must bring along everything they need. This adds expense and complexity to an already ambitious endeavor – and limits where spacecraft can go. As a way to ease that packing burden, Sigrid Close, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University, is finding ways to treat the space environment as a collection of resources.

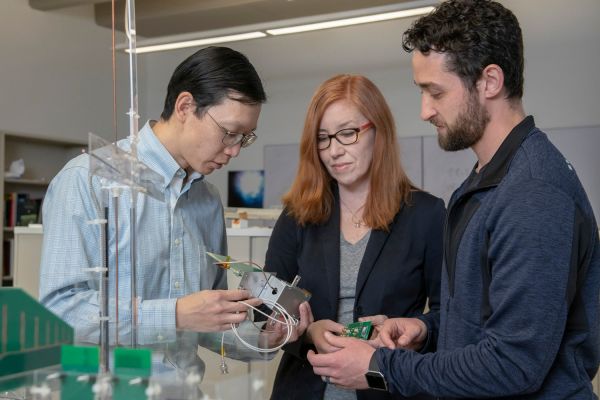

Research Engineer Nicolas Lee, left, works with PhD student Sean Young, right, on an energy harvesting antenna used in their hypervelocity impact experiments at NASA Ames under the supervision of Associate Professor Sigrid Close. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

“For us to be a space-faring species, we need to better understand what’s out there,” said Nicolas Lee, research engineer in Close’s lab and her former graduate student. “We want to open up access to the solar system in a way that takes advantage of the space environment, while also protecting our spacecraft from it.”

The Space Environment and Satellite Systems lab members don’t expect to pluck food and water from the cosmos. Instead, they are focused on plasma – the collection of gaseous charged particles that surrounds planets and asteroids. They think plasma could power longer range spacecraft or enable a new way of surveying asteroids for mining, an application that could provide possible materials for use on Earth and in space.

“We like ideas that verge on science fiction,” Close said. “We have to do work that’s revolutionary, rather than only evolutionary, if we’re going to get to that next step in space exploration.”

Plasma power

We can witness plasma as lightning and in neon signs but it’s also abundant throughout the universe in places with strong magnetic fields – the sun is big ball of plasma and the Earth’s upper atmosphere is plasma, too. The Close lab has set its sights on plasma because spacecraft are regularly immersed in it.

One idea the researchers have is to power spacecraft or their subsystems with plasma. As spacecraft venture farther from the sun, they cannot rely on solar power. But in passing by certain planets, like Jupiter and Saturn, they can become surrounded by higher density plasma, which causes the vehicles to build up a negative charge. The researchers are hoping they could capture that charge to power spacecraft on their way out of the solar system.

“If it works, it has the ability to expand the types of missions that we can actually fly,” said Sean Young, a graduate student working with Close on this project, which is part of a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship. “We could do many missions with CubeSats – small, modular satellites – in the outer solar system that we wouldn’t be able to do now.”

As for its role in asteroid mining, the lab scientists think the small plumes of plasma that an asteroid emits after a meteoroid strike could reveal the materials within. Working off this idea, they have proposed a parent spacecraft that distributes 10 to 20 small sensors around an asteroid to report the location, timing and speed of plasma that washes over them. These measurements could indicate whether the asteroid contains water, organics or any elements of interest.

This set of spacecraft and sensors would weigh somewhere between one-fifth and half as much as systems currently sent to explore asteroids, which means one mission could send out several sets to explore multiple asteroids at once. The project is called Meteoroid Impact Detection for Exploration of Asteroids (MIDEA) and is part of the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts Program, which funds radically innovative visions that are in the early stages of development.

Our connection to space

Close pictures her work as part of a larger story of aspirational space research that has previously led to versatile innovations, including GPS, laptops, water purifiers, wireless headsets and artificial limbs. Where some only see the hype around setting up colonies on the moon or Mars, Close sees technologies that could someday allow people to stay on Earth in the face of extreme environmental changes.

“Many people don’t understand why we spend our resources on space research and exploration when we could use them on something else,” Close said. “But we’ve all benefited so much from the space program and there’s so much more to discover.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.