A 17th-century volume of William Shakespeare’s plays, a piano roll recorded by Claude Debussy and a 1959 edition of the Green Book, a travel guide for African Americans driving through the Jim Crow-era South, are among dozens of unique artifacts now on display at Stanford’s Green Library Bing Wing as part of a new exhibition.

Scholars Select: Special Collections in Action, which runs through April 14, highlights 36 rare books and other relics held in Green Library collections that are valuable to the research of scholars at Stanford. Each item was chosen by a Stanford researcher as the one artifact they would take to study if they were on a desert island.

The exhibition celebrates 100 years since the opening in July 1919 of Green Library’s building, known back then as Stanford’s Main Library. Over that time, the library’s collections have grown from 3,000 volumes in 1891 to about 12 million assets today.

Below are 12 Stanford faculty members with their chosen items in a series of portraits by University Photographer Linda A. Cicero. Click on each photo to read what the faculty member says about the cherished artifact.

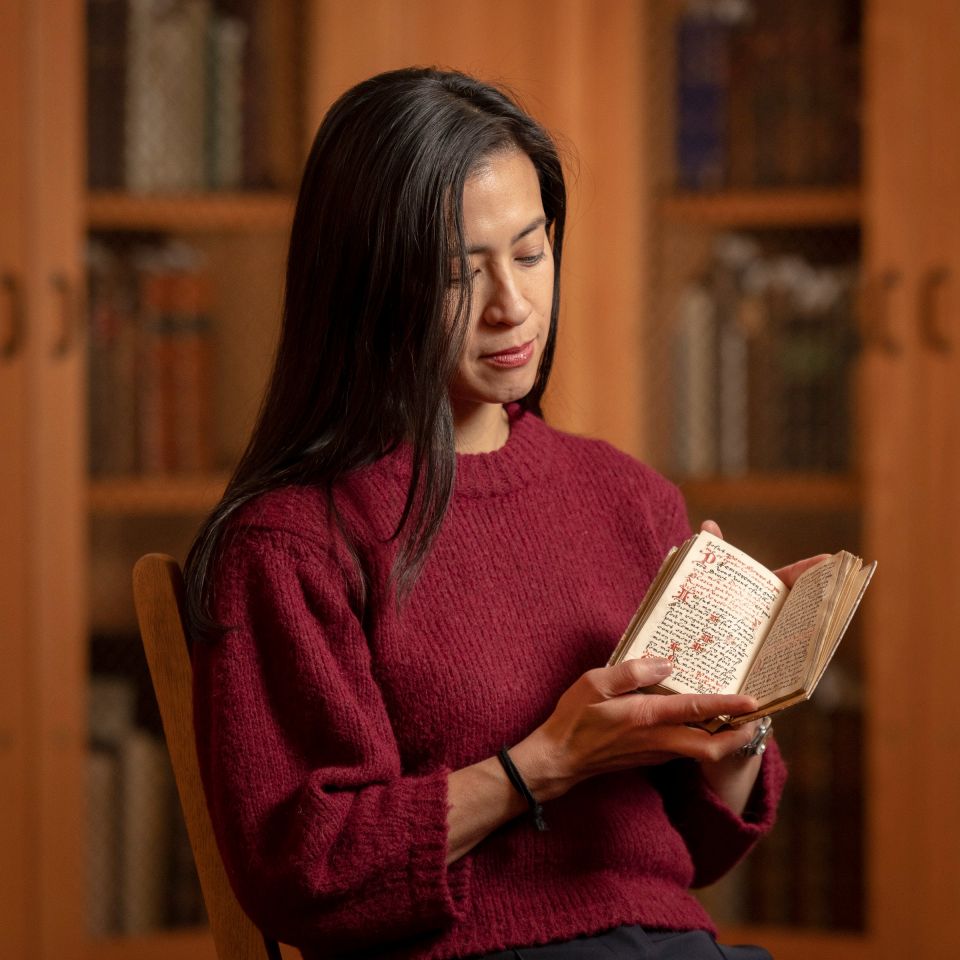

Marisa Galvez holds a contemplative manuscript from the 16th century made for a Franciscan nun

Marisa Galvez

Associate Professor of French and Italian

Recomandacion de l’estat de la religion, France, ca. 1500

“With this small, contemplative manuscript made for a Franciscan nun, we can imagine how the faithful used manuscripts in an interactive and performative way: as a personal guide for prayer and daily rituals. In addition to including meditations on the Sacrament, prayers to Christ and meditations on Christ’s temptations in the desert, the manuscript also includes a series of prayers to be said when putting on one’s clothes in the morning. On fol. 102 v. (shown), as she gets dressed, the speaker prays that the Christ child and Mary inhabit various body parts (head, eyes, ears). The ritual engages the body and mind as the nun methodically enlists different parts of her person in a contemplative state.

“Students taking my introductory medieval French courses are astonished that they can puzzle out the French after they get used to the script, and they view the history of vernacular languages in a different light when they can read it in such a personal manuscript book. They concretely apprehend the devotional use of vernacular language in the premodern era.”

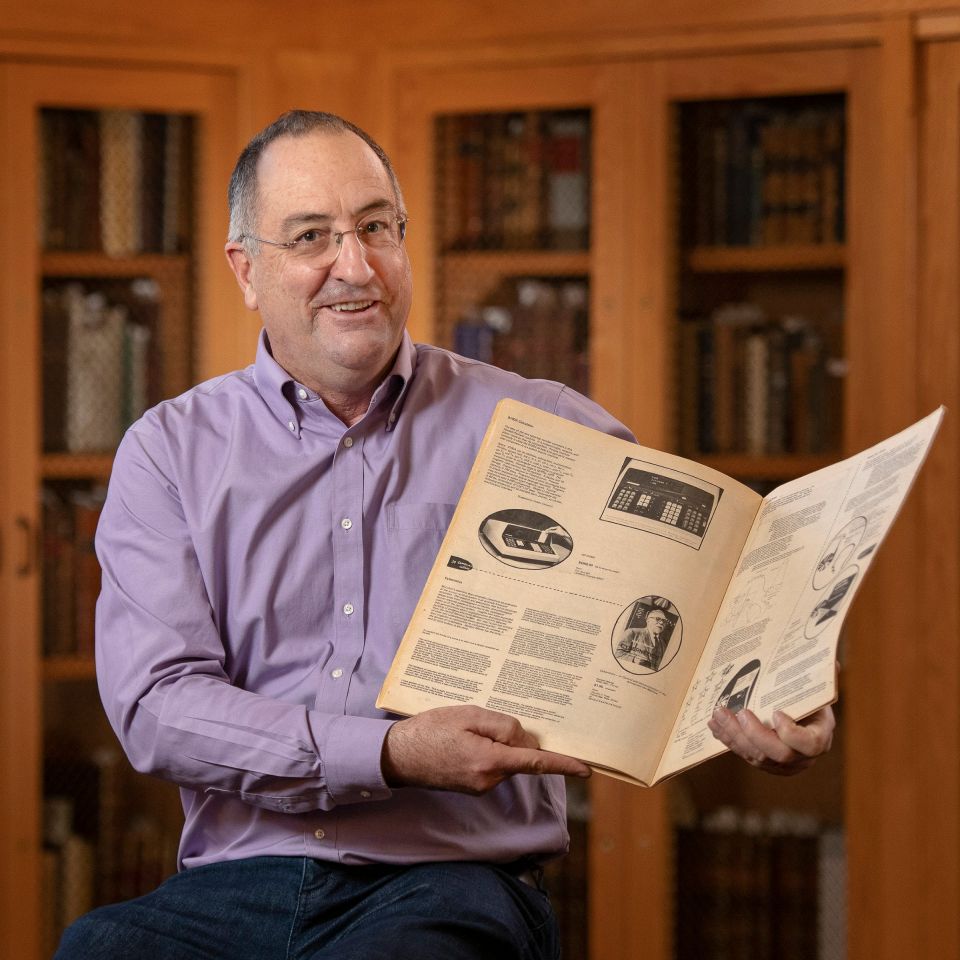

Fred Turner with the Fall 1968 Whole Earth Catalog

Fred Turner

Harry and Norman Chandler Professor of Communication

Whole Earth Catalog, First Issue, Fall 1968

“Looking at it today, you might never guess how this funky, stapled together thing called the Whole Earth Catalog changed how we think about the internet. In early 1968, tens of thousands of Americans were heading back to the land in what remains the largest commune movement in American history. Multimedia artist and Stanford alumnus Stewart Brand and his wife, Lois, wanted to help them find the tools they’d need. The catalog they created became a model of a world connected by information technologies, a world in which individuals would be free to create the connections they saw fit.

“Silicon Valley innovators from Alan Kay to Steve Jobs later claimed to have seen in the Whole Earth Catalog a model for what the internet would become. Today we can see that it was a paper-bound search engine. And it continues to remind us of the many ways that the hope to build communities of consciousness that animated the communes of the 1960s continues to shape our dreams of what the internet might become.”

Cintia Santana with Hojas de hierba (Leaves of Grass) translated by Jorge Luis Borges

Cintia Santana

Senior Lecturer, Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages

Walt Whitman, Hojas de hierba (Leaves of Grass), selected and translated by Jorge Luis Borges, with illustrations by Antonio Berni, Buenos Aires: Juárez, 1969

“A woodblock print of Walt Whitman by Antonio Berni opens this handsome edition of Jorge Luis Borges’ selective translation of Leaves of Grass. Over time, the print has left the palest of traces on the facing title page. The faint inverse of Whitman’s likeness provides a visually rich metaphor, a near-palimpsest that points to the layered and contiguous acts that comprise reading, writing and translation.

“As a teenager living in Geneva, Borges first encountered Leaves of Grass in a German translation by Johannes Schlaf. He soon ordered an English edition. As early as 1927, he announced that he was working on its translation. His translation, however, would not appear until 1969.

“If Whitman’s ‘I’ contains multitudes, the reader is explicitly addressed among these: ‘I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.’ Borges contributes to this complexity by adding the translator: a figure both reader and writer.

“Borges’ essays on translation often underscored the instability of an original text. He considered a translation to be a subsequent draft, albeit one with a particularly visible antecedent, potentially capable of improving on the original. Leaves of Grass provides yet another example of an ‘original’ work in constant change up until Whitman’s ‘death-bed’ edition.

“Hojas de hierba, with its yellowing pages and small tears in its paper cover, materially foregrounds how time inexorably impresses change on a text, its readers and language itself.”

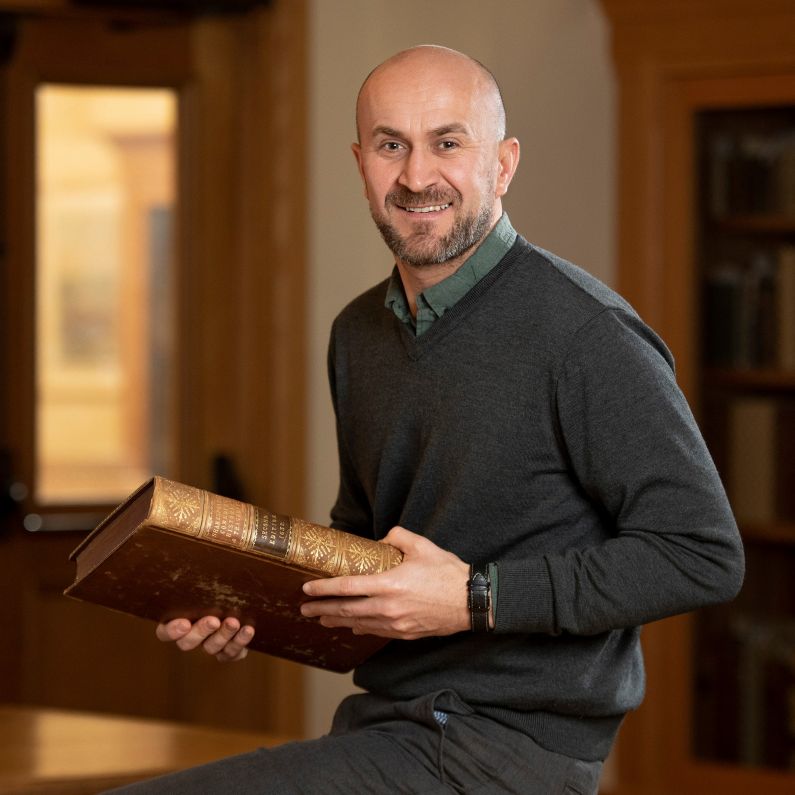

Ivan Lupić with the 1632 Shakespeare folio

Ivan Lupić

Assistant Professor of English

William Shakespeare, Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Published According to the True Originall Copies, London: Printed by Tho. Cotes, for William Aspley, 1632

“This volume, published in 1632, marks the beginning of Shakespearean textual criticism as a form of creative expression. Set from a corrected copy of the first edition (1623), the Shakespeare second folio shows evidence of significant editorial intervention. In addition to correcting obvious typographical errors, the editors of the second folio attempted to emend the text not by consulting the earlier quarto editions, when these existed, but by trying to guess what Shakespeare may have actually written. In this process of reconstruction, they were largely guided by their imagination, deciding what the best reading might be with respect to the story, the dramatic context or contemporary language usage. In many instances, they successfully restored the readings of the quartos without knowing it; in other instances, they provided solutions so successful that later editors simply followed them.

“For example, when early in King Lear Cordelia is disowned by her father, he swears by, among other things, ‘the mistress of Hecate.’ So at least the quarto edition (1608) would have it. The first folio read, instead, ‘the miseries of Hecate.’ The editors of the second folio emended the phrase to read ‘the mysteries of Hecate,’ which is the reading most commonly found in modern editions of Shakespeare. The editors of the second folio remain anonymous, but we should remember that when we read Shakespeare we may be also be, on occasion, reading them.”

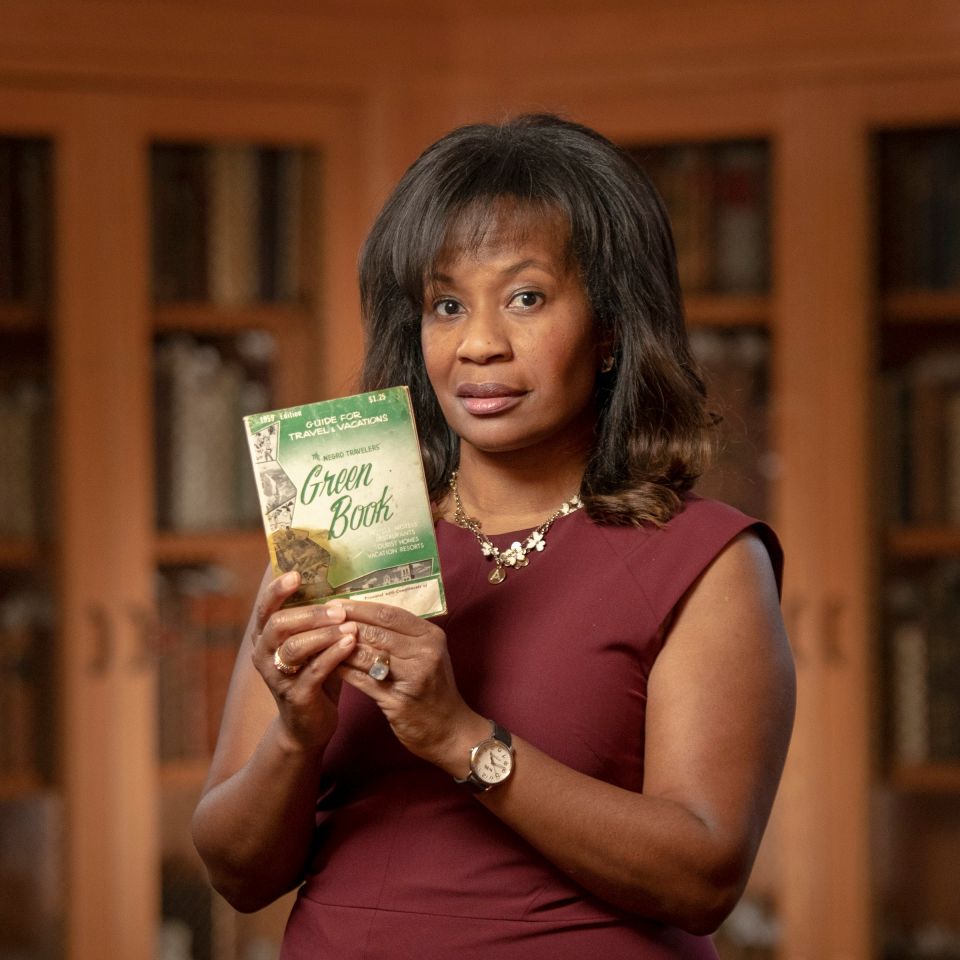

Allyson Hobbs with The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, 1959

Allyson Hobbs

Associate Professor of American History

Director of African and African American Studies

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, New York: Victor H. Green & Company, 1959

“In 1953, the singer Dinah Shore famously urged Americans to ‘See the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet,’ crooning, ‘On the highway, or on a road along a levee, the performance is sweeter, nothing can beat her, life is completer in a Chevy.’

“Most African American motorists would not have access to the midcentury pleasures of taking to the road due to the racial discrimination that they were certain to face. African Americans were largely left out of the car culture that flowered in the post-World War II period.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book: An International Travel Guide, first printed in 1936 and more commonly known as the Green Book, offered black roadsters 80 pages of listings of welcoming hotels, boarding houses, restaurants and service stations. The introduction stated its goal to keep the black motorist ‘from running into difficulties, embarrassments, and to make his trips more enjoyable.’ Victor H. Green, a Harlem postal worker, published 15,000 travel guides annually. A 20th-century version of the network created by the Underground Railroad, the Green Book created a geography that was hidden to whites yet apparent and instrumental to blacks.

“Victor Green hoped that a day would come when the guide would no longer be necessary. The last Green Book was published in 1965 after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which included provisions to end racial segregation in public accommodations. Black travelers continued to rely upon it for decades, affirming the guide’s tagline: ‘Carry your Green Book with you. You may need it.’”

Lazar Fleishman with a 1924 manuscript of Lev Nikolaevich Gomolitskii’s poem “Edinoborets”

Lazar Fleishman

Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures

Leon Gomolicki, “Edinoborets,” 1924

“This manuscript is the work of noted Polish writer Leon Gomolicki (1903–1989). Born Lev Nikolaevich Gomolitskii in St. Petersburg to Russianized parents of Polish descent, neither he nor his parents spoke any Polish when they settled during World War I in the small Volhynian town of Ostróg that was transferred in 1921 to the newly independent Polish state. From his adolescence Lev was writing poems in Russian.

“Gomolitskii’s first two poetry collections were published when he was 15 (Ostróg, 1918) and 18 years old (Warsaw, 1921); thereafter, his name vanished from print for a long time. Yet he didn’t stop writing poetry and, in Ostróg gymnasium, he joined the student literary circle ‘Rosary’ that during five years of its existence reportedly produced 47 ‘volumes’ of poetry and prose – handwritten or typed and printed as collotypes. The displayed manuscript, Gomolitskii’s poem ‘Edinoborets’ (1924) evidently belongs to this group of publications. It describes the author’s battle with himself and the spiritual torments the battle engenders. The holograph testifies also to the young poet’s interest in calligraphy and visual art. I found this beautiful and deeply moving poem in Special Collections as I was preparing with two colleagues from Europe the first annotated three-volume edition of the Collected Works of Lev Gomolitskii’s Russian Period (Moscow, 2011). Now I discuss the peculiar features of Gomolitskii’s poetry every year in my class on Russian versification.”

Krish Seetah with the 1894 American first edition of The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

Krish Seetah

Assistant Professor of Anthropology

Rudyard Kipling, The Jungle Book, First American Edition, New York, Century: 1894

“The human-animal relationship is dynamic, all encompassing and durable. Around the world, we see evidence of complex interactions between people and the animals around them, both domesticated and wild. However, the individual circumstances of these interactions are hugely complicated, going far beyond direct human-animal contact to incorporate social, ecological and spiritual contexts.

“Few authors have captured the inherent nuance of the human-animal relationship as uniquely as Kipling. While the magic of Mowgli’s story is narrated in a way that is immediately recognizable, Kipling’s style coalesces fact with fiction in a way that shows astounding attention to detail.

“This attention to detail was apparent to me from the very beginning of my career teaching students how to identify bone.

“I had re-read The White Seal the previous evening, noting that Kipling tells us that the Sea Cow (Sirenia: dugong, manatees and the extinct Steller’s Sea Cow) has just six, not seven, cervical vertebras, making it morose. I couldn’t believe it when, during teaching, I discovered a little used specimen from the reference collection: the fused first and second vertebra of a dugong; effectively, leaving dugongs with only six cervical vertebras.

“The Jungle Book continues to feature directly in my courses, teaching my students and me to see the depth of how we interact with the world around us.”

Caroline Winterer with a letter written by Benjamin Franklin, describing observations on electricity, 1757

Caroline Winterer

Director and Anthony P. Meier Family Professor in the Humanities, Stanford Humanities Center; Professor of History

Observations on Electricity and Other Natural Phenomena: Letter from Benjamin Franklin to John Lining, 14 April 1757

“Just before leaving America for England in 1757, Benjamin Franklin dashed off this eight-page letter to John Lining, a physician who lived in the yellow-fever-ridden swamp known as South Carolina. A great believer in the influence of climate on human health, Lining had spent a year meticulously measuring his own fluctuating weight and temperature in the hopes of connecting climate to disease. He reported these observations to the Royal Society in London, which brought his experiments to the attention of the international scientific community, including Benjamin Franklin.

“This letter by Franklin addresses their mutual fascination with the great mystery of what makes the human body warm or cold. Was it climate or electricity? Franklin bet on electricity, speculating that digested plants give off a ‘Fluid called Fire,’ which powered the human furnace.

“This letter is fascinating to Stanford students. Not only is the topic strange to their eye (who writes eight-page letters about digestion?), it shows them the importance of the archive. This letter is original in the sense that Franklin penned it. But it is also a copy: A slightly different version exists in other archives, a reminder of the widespread culture of copying that flourished during this great age of letter-writing. Even though Franklin personally wrote thousands of letters, he also made copies of many of those letters for a variety of purposes, such as record-keeping.”

Al Camarillo with the 1939 minutes of the first national meeting of the first pan-Latino civil rights organization in the United States

Albert M. Camarillo

Professor of History, Emeritus

Congress of Spanish-Speaking People (El Congreso de Pueblos de Hablan Española), “Digest of Proceedings,” First National Congress, Los Angeles, 1939

“In the 1970s I conducted oral history interviews with Mexican American civil rights leaders in Los Angeles. I had heard from many of these veteran organizers about the Congress of Spanish-Speaking People that formed in 1939, the first pan-Latino civil rights organization in the United States. However, I had not yet uncovered any archival documentation about this organization until the late 1970s when, by chance, I came across the ‘Digest of Proceedings’ of the First National Congress when reviewing non-related material included in the Ernesto Galarza Collection.

“The ‘Digest of Proceedings’ was a gold mine. It provided detailed information about the agenda and platform as well as the outcome of the first meeting of the Congress. Although I had already interviewed several participants and leaders of the Congress, this document in the Galarza Collection – the only copy known to exist – allowed me to see how the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s was based, in part, on an agenda for social justice, worker rights and civil rights articulated by Mexican American and other Latino leaders a generation earlier. My research and teaching about the ‘long’ history of Mexican American civil rights was significantly changed as a result of reading this rare document.”

George Barth examines a reproducing piano roll of a performance by Claude Debussy

George Barth

Billie Bennett Achilles Director of Keyboard Programs and Professor (Teaching) of Music

Stanford’s Player Piano Project, Welte-Mignon red roll number 2378, Denis Condon Collection of Reproducing Pianos and Rolls

“In 1913, Claude Debussy recorded his own performance of La cathédrale engloutie, the 10th of his 1910 Préludes, on a reproducing piano roll. Debussy’s programmatic sketch evokes an ancient Breton legend of the sunken city of Ys, those eerie occasions when its cathedral appears to rise from the sea, bells tolling, chants echoing above the swells of the waves.

“Sadly though, the composer’s exquisite manuscript – and Durand’s first and early editions – posed an intractable rhythmic problem for performers, a problem whose solution was known only to a select few who had heard Debussy play. After his death, even acclaimed interpreters such as Walter Gieseking, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Leopold Stokowski wrestled with text alone – and lost.

“So it remained, until Debussy’s roll performance came to light once again, revealing a conception quite unlike what seems to appear on the printed page. From the reproducing piano emerge entirely fresh proportions for the prelude as a whole, much more familiar proportions that reflect the Golden Sections that typify Debussy’s compositions from 1904 through much of the rest of his life. This conundrum and the composer’s solution are just one example of the myriad questions that fascinate and bedevil performers of notated Western music, many of which we explore with the rolls and roll players of Stanford’s extraordinary Condon Collection.”

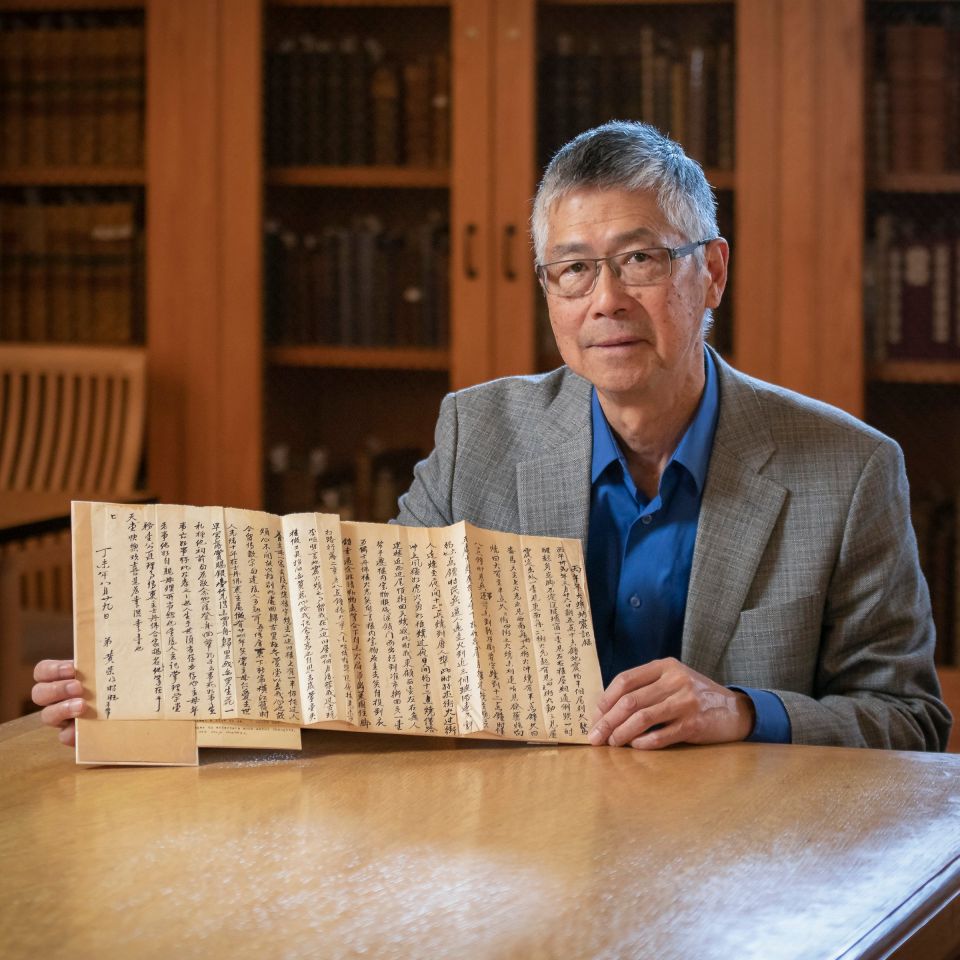

Gordon Chang with a letter from Ah Wing, reflecting on his longtime employment as the Stanford Family’s majordomo

Gordon H. Chang

Olive H. Palmer Professor in Humanities and Professor of History

Ah Wing letter to Stanford University (undated)

“A rhetorical question circulates among Chinese Americans: Why are the tile roofs of Stanford University red? The answer: They are stained with the blood of Chinese railroad workers who died constructing the transcontinental railroad for Leland Stanford.

“Stanford is recalled by some as a robber baron and exploiter of Chinese whose labor made him one of the world’s richest men. But the Stanford name inspires a different meaning for other Chinese Americans, who view Jane and Leland Stanford as benefactors and protectors of Chinese from racist mobs. They employed hundreds of Chinese on ‘The Farm’ and at their other residences as household workers, field hands, gardeners and cooks. Chinese helped construct the early infrastructure of the university, including the foundations for early buildings and roads.

“Leland and Jane also developed close, personal relationships with many Chinese. One of the most moving testimonies to this is a letter sent from China by a man named Ah Wing, who had worked for the Stanfords in Palo Alto and San Francisco for decades. In the early 20th century, the university requested his recollections of his years with the Stanfords and the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. The letter, shown here along with a partial transcription, tells of Ah Wing’s filial devotion to his employers. It highlights the complexity of the Stanford legacy and their relationship with Chinese in California, and is emblematic of the trans-Pacific and ethnic history I have explored in my recent scholarship.”

Shane Denson with the September 1974 issue of the People’s Computer Company newsletter

Shane Denson

Assistant Professor, Film & Media Studies Program

Department of Art & Art History

People’s Computer Company Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 1, September 1974

“A letter published in the September 1974 issue of People’s Computer Company sheds light on an interesting entanglement of the early history of computer games, broader popular-cultural imaginations and the formation of what Benedict Anderson has called ‘imagined communities.’ Its author, Robert C. Leedom, describes the arduous task of typing modified code into a computer in order to play Super Star Trek, a game that would play a special role in the home computing revolution, as its source code’s inclusion in the 1978 edition of David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games was instrumental in making that book the first million-selling computer book. The game would go on to be packaged with new IBM PCs as part of the included GW-BASIC distribution, and it inspired countless ports, clones and spin-offs in the 1980s and beyond.

“Written years earlier, Leedom’s letter documents a context and a form of engagement with computer games quite different from today’s popular videogames. Here, the game’s underlying code is necessarily exposed to the user, who must type it in by hand; gameplay takes place not in the living room but in the interstices of military projects’ downtime; and the authorship of the game itself is distributed amongst players who write, rewrite, copy and modify code. The game described by Leedom points to a mismatch between the space-age fantasies of Star Trek and the realities of computing in the 1970s, but it also inspires questions about the historical conditions that gave rise to today’s gamers.”

Marisa Galvez holds a contemplative manuscript from the 16th century made for a Franciscan nun

Marisa Galvez

Associate Professor of French and Italian

Recomandacion de l’estat de la religion, France, ca. 1500

“With this small, contemplative manuscript made for a Franciscan nun, we can imagine how the faithful used manuscripts in an interactive and performative way: as a personal guide for prayer and daily rituals. In addition to including meditations on the Sacrament, prayers to Christ and meditations on Christ’s temptations in the desert, the manuscript also includes a series of prayers to be said when putting on one’s clothes in the morning. On fol. 102 v. (shown), as she gets dressed, the speaker prays that the Christ child and Mary inhabit various body parts (head, eyes, ears). The ritual engages the body and mind as the nun methodically enlists different parts of her person in a contemplative state.

“Students taking my introductory medieval French courses are astonished that they can puzzle out the French after they get used to the script, and they view the history of vernacular languages in a different light when they can read it in such a personal manuscript book. They concretely apprehend the devotional use of vernacular language in the premodern era.”

Fred Turner with the Fall 1968 Whole Earth Catalog

Fred Turner

Harry and Norman Chandler Professor of Communication

Whole Earth Catalog, First Issue, Fall 1968

“Looking at it today, you might never guess how this funky, stapled together thing called the Whole Earth Catalog changed how we think about the internet. In early 1968, tens of thousands of Americans were heading back to the land in what remains the largest commune movement in American history. Multimedia artist and Stanford alumnus Stewart Brand and his wife, Lois, wanted to help them find the tools they’d need. The catalog they created became a model of a world connected by information technologies, a world in which individuals would be free to create the connections they saw fit.

“Silicon Valley innovators from Alan Kay to Steve Jobs later claimed to have seen in the Whole Earth Catalog a model for what the internet would become. Today we can see that it was a paper-bound search engine. And it continues to remind us of the many ways that the hope to build communities of consciousness that animated the communes of the 1960s continues to shape our dreams of what the internet might become.”

Cintia Santana with Hojas de hierba (Leaves of Grass) translated by Jorge Luis Borges

Cintia Santana

Senior Lecturer, Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages

Walt Whitman, Hojas de hierba (Leaves of Grass), selected and translated by Jorge Luis Borges, with illustrations by Antonio Berni, Buenos Aires: Juárez, 1969

“A woodblock print of Walt Whitman by Antonio Berni opens this handsome edition of Jorge Luis Borges’ selective translation of Leaves of Grass. Over time, the print has left the palest of traces on the facing title page. The faint inverse of Whitman’s likeness provides a visually rich metaphor, a near-palimpsest that points to the layered and contiguous acts that comprise reading, writing and translation.

“As a teenager living in Geneva, Borges first encountered Leaves of Grass in a German translation by Johannes Schlaf. He soon ordered an English edition. As early as 1927, he announced that he was working on its translation. His translation, however, would not appear until 1969.

“If Whitman’s ‘I’ contains multitudes, the reader is explicitly addressed among these: ‘I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.’ Borges contributes to this complexity by adding the translator: a figure both reader and writer.

“Borges’ essays on translation often underscored the instability of an original text. He considered a translation to be a subsequent draft, albeit one with a particularly visible antecedent, potentially capable of improving on the original. Leaves of Grass provides yet another example of an ‘original’ work in constant change up until Whitman’s ‘death-bed’ edition.

“Hojas de hierba, with its yellowing pages and small tears in its paper cover, materially foregrounds how time inexorably impresses change on a text, its readers and language itself.”

Ivan Lupić with the 1632 Shakespeare folio

Ivan Lupić

Assistant Professor of English

William Shakespeare, Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Published According to the True Originall Copies, London: Printed by Tho. Cotes, for William Aspley, 1632

“This volume, published in 1632, marks the beginning of Shakespearean textual criticism as a form of creative expression. Set from a corrected copy of the first edition (1623), the Shakespeare second folio shows evidence of significant editorial intervention. In addition to correcting obvious typographical errors, the editors of the second folio attempted to emend the text not by consulting the earlier quarto editions, when these existed, but by trying to guess what Shakespeare may have actually written. In this process of reconstruction, they were largely guided by their imagination, deciding what the best reading might be with respect to the story, the dramatic context or contemporary language usage. In many instances, they successfully restored the readings of the quartos without knowing it; in other instances, they provided solutions so successful that later editors simply followed them.

“For example, when early in King Lear Cordelia is disowned by her father, he swears by, among other things, ‘the mistress of Hecate.’ So at least the quarto edition (1608) would have it. The first folio read, instead, ‘the miseries of Hecate.’ The editors of the second folio emended the phrase to read ‘the mysteries of Hecate,’ which is the reading most commonly found in modern editions of Shakespeare. The editors of the second folio remain anonymous, but we should remember that when we read Shakespeare we may be also be, on occasion, reading them.”

Allyson Hobbs with The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, 1959

Allyson Hobbs

Associate Professor of American History

Director of African and African American Studies

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, New York: Victor H. Green & Company, 1959

“In 1953, the singer Dinah Shore famously urged Americans to ‘See the U.S.A. in your Chevrolet,’ crooning, ‘On the highway, or on a road along a levee, the performance is sweeter, nothing can beat her, life is completer in a Chevy.’

“Most African American motorists would not have access to the midcentury pleasures of taking to the road due to the racial discrimination that they were certain to face. African Americans were largely left out of the car culture that flowered in the post-World War II period.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book: An International Travel Guide, first printed in 1936 and more commonly known as the Green Book, offered black roadsters 80 pages of listings of welcoming hotels, boarding houses, restaurants and service stations. The introduction stated its goal to keep the black motorist ‘from running into difficulties, embarrassments, and to make his trips more enjoyable.’ Victor H. Green, a Harlem postal worker, published 15,000 travel guides annually. A 20th-century version of the network created by the Underground Railroad, the Green Book created a geography that was hidden to whites yet apparent and instrumental to blacks.

“Victor Green hoped that a day would come when the guide would no longer be necessary. The last Green Book was published in 1965 after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which included provisions to end racial segregation in public accommodations. Black travelers continued to rely upon it for decades, affirming the guide’s tagline: ‘Carry your Green Book with you. You may need it.’”

Lazar Fleishman with a 1924 manuscript of Lev Nikolaevich Gomolitskii’s poem “Edinoborets”

Lazar Fleishman

Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures

Leon Gomolicki, “Edinoborets,” 1924

“This manuscript is the work of noted Polish writer Leon Gomolicki (1903–1989). Born Lev Nikolaevich Gomolitskii in St. Petersburg to Russianized parents of Polish descent, neither he nor his parents spoke any Polish when they settled during World War I in the small Volhynian town of Ostróg that was transferred in 1921 to the newly independent Polish state. From his adolescence Lev was writing poems in Russian.

“Gomolitskii’s first two poetry collections were published when he was 15 (Ostróg, 1918) and 18 years old (Warsaw, 1921); thereafter, his name vanished from print for a long time. Yet he didn’t stop writing poetry and, in Ostróg gymnasium, he joined the student literary circle ‘Rosary’ that during five years of its existence reportedly produced 47 ‘volumes’ of poetry and prose – handwritten or typed and printed as collotypes. The displayed manuscript, Gomolitskii’s poem ‘Edinoborets’ (1924) evidently belongs to this group of publications. It describes the author’s battle with himself and the spiritual torments the battle engenders. The holograph testifies also to the young poet’s interest in calligraphy and visual art. I found this beautiful and deeply moving poem in Special Collections as I was preparing with two colleagues from Europe the first annotated three-volume edition of the Collected Works of Lev Gomolitskii’s Russian Period (Moscow, 2011). Now I discuss the peculiar features of Gomolitskii’s poetry every year in my class on Russian versification.”

Krish Seetah with the 1894 American first edition of The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

Krish Seetah

Assistant Professor of Anthropology

Rudyard Kipling, The Jungle Book, First American Edition, New York, Century: 1894

“The human-animal relationship is dynamic, all encompassing and durable. Around the world, we see evidence of complex interactions between people and the animals around them, both domesticated and wild. However, the individual circumstances of these interactions are hugely complicated, going far beyond direct human-animal contact to incorporate social, ecological and spiritual contexts.

“Few authors have captured the inherent nuance of the human-animal relationship as uniquely as Kipling. While the magic of Mowgli’s story is narrated in a way that is immediately recognizable, Kipling’s style coalesces fact with fiction in a way that shows astounding attention to detail.

“This attention to detail was apparent to me from the very beginning of my career teaching students how to identify bone.

“I had re-read The White Seal the previous evening, noting that Kipling tells us that the Sea Cow (Sirenia: dugong, manatees and the extinct Steller’s Sea Cow) has just six, not seven, cervical vertebras, making it morose. I couldn’t believe it when, during teaching, I discovered a little used specimen from the reference collection: the fused first and second vertebra of a dugong; effectively, leaving dugongs with only six cervical vertebras.

“The Jungle Book continues to feature directly in my courses, teaching my students and me to see the depth of how we interact with the world around us.”

Caroline Winterer with a letter written by Benjamin Franklin, describing observations on electricity, 1757

Caroline Winterer

Director and Anthony P. Meier Family Professor in the Humanities, Stanford Humanities Center; Professor of History

Observations on Electricity and Other Natural Phenomena: Letter from Benjamin Franklin to John Lining, 14 April 1757

“Just before leaving America for England in 1757, Benjamin Franklin dashed off this eight-page letter to John Lining, a physician who lived in the yellow-fever-ridden swamp known as South Carolina. A great believer in the influence of climate on human health, Lining had spent a year meticulously measuring his own fluctuating weight and temperature in the hopes of connecting climate to disease. He reported these observations to the Royal Society in London, which brought his experiments to the attention of the international scientific community, including Benjamin Franklin.

“This letter by Franklin addresses their mutual fascination with the great mystery of what makes the human body warm or cold. Was it climate or electricity? Franklin bet on electricity, speculating that digested plants give off a ‘Fluid called Fire,’ which powered the human furnace.

“This letter is fascinating to Stanford students. Not only is the topic strange to their eye (who writes eight-page letters about digestion?), it shows them the importance of the archive. This letter is original in the sense that Franklin penned it. But it is also a copy: A slightly different version exists in other archives, a reminder of the widespread culture of copying that flourished during this great age of letter-writing. Even though Franklin personally wrote thousands of letters, he also made copies of many of those letters for a variety of purposes, such as record-keeping.”

Al Camarillo with the 1939 minutes of the first national meeting of the first pan-Latino civil rights organization in the United States

Albert M. Camarillo

Professor of History, Emeritus

Congress of Spanish-Speaking People (El Congreso de Pueblos de Hablan Española), “Digest of Proceedings,” First National Congress, Los Angeles, 1939

“In the 1970s I conducted oral history interviews with Mexican American civil rights leaders in Los Angeles. I had heard from many of these veteran organizers about the Congress of Spanish-Speaking People that formed in 1939, the first pan-Latino civil rights organization in the United States. However, I had not yet uncovered any archival documentation about this organization until the late 1970s when, by chance, I came across the ‘Digest of Proceedings’ of the First National Congress when reviewing non-related material included in the Ernesto Galarza Collection.

“The ‘Digest of Proceedings’ was a gold mine. It provided detailed information about the agenda and platform as well as the outcome of the first meeting of the Congress. Although I had already interviewed several participants and leaders of the Congress, this document in the Galarza Collection – the only copy known to exist – allowed me to see how the Chicano civil rights movement of the 1960s was based, in part, on an agenda for social justice, worker rights and civil rights articulated by Mexican American and other Latino leaders a generation earlier. My research and teaching about the ‘long’ history of Mexican American civil rights was significantly changed as a result of reading this rare document.”

George Barth examines a reproducing piano roll of a performance by Claude Debussy

George Barth

Billie Bennett Achilles Director of Keyboard Programs and Professor (Teaching) of Music

Stanford’s Player Piano Project, Welte-Mignon red roll number 2378, Denis Condon Collection of Reproducing Pianos and Rolls

“In 1913, Claude Debussy recorded his own performance of La cathédrale engloutie, the 10th of his 1910 Préludes, on a reproducing piano roll. Debussy’s programmatic sketch evokes an ancient Breton legend of the sunken city of Ys, those eerie occasions when its cathedral appears to rise from the sea, bells tolling, chants echoing above the swells of the waves.

“Sadly though, the composer’s exquisite manuscript – and Durand’s first and early editions – posed an intractable rhythmic problem for performers, a problem whose solution was known only to a select few who had heard Debussy play. After his death, even acclaimed interpreters such as Walter Gieseking, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Leopold Stokowski wrestled with text alone – and lost.

“So it remained, until Debussy’s roll performance came to light once again, revealing a conception quite unlike what seems to appear on the printed page. From the reproducing piano emerge entirely fresh proportions for the prelude as a whole, much more familiar proportions that reflect the Golden Sections that typify Debussy’s compositions from 1904 through much of the rest of his life. This conundrum and the composer’s solution are just one example of the myriad questions that fascinate and bedevil performers of notated Western music, many of which we explore with the rolls and roll players of Stanford’s extraordinary Condon Collection.”

Gordon Chang with a letter from Ah Wing, reflecting on his longtime employment as the Stanford Family’s majordomo

Gordon H. Chang

Olive H. Palmer Professor in Humanities and Professor of History

Ah Wing letter to Stanford University (undated)

“A rhetorical question circulates among Chinese Americans: Why are the tile roofs of Stanford University red? The answer: They are stained with the blood of Chinese railroad workers who died constructing the transcontinental railroad for Leland Stanford.

“Stanford is recalled by some as a robber baron and exploiter of Chinese whose labor made him one of the world’s richest men. But the Stanford name inspires a different meaning for other Chinese Americans, who view Jane and Leland Stanford as benefactors and protectors of Chinese from racist mobs. They employed hundreds of Chinese on ‘The Farm’ and at their other residences as household workers, field hands, gardeners and cooks. Chinese helped construct the early infrastructure of the university, including the foundations for early buildings and roads.

“Leland and Jane also developed close, personal relationships with many Chinese. One of the most moving testimonies to this is a letter sent from China by a man named Ah Wing, who had worked for the Stanfords in Palo Alto and San Francisco for decades. In the early 20th century, the university requested his recollections of his years with the Stanfords and the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. The letter, shown here along with a partial transcription, tells of Ah Wing’s filial devotion to his employers. It highlights the complexity of the Stanford legacy and their relationship with Chinese in California, and is emblematic of the trans-Pacific and ethnic history I have explored in my recent scholarship.”

Shane Denson with the September 1974 issue of the People’s Computer Company newsletter

Shane Denson

Assistant Professor, Film & Media Studies Program

Department of Art & Art History

People’s Computer Company Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 1, September 1974

“A letter published in the September 1974 issue of People’s Computer Company sheds light on an interesting entanglement of the early history of computer games, broader popular-cultural imaginations and the formation of what Benedict Anderson has called ‘imagined communities.’ Its author, Robert C. Leedom, describes the arduous task of typing modified code into a computer in order to play Super Star Trek, a game that would play a special role in the home computing revolution, as its source code’s inclusion in the 1978 edition of David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games was instrumental in making that book the first million-selling computer book. The game would go on to be packaged with new IBM PCs as part of the included GW-BASIC distribution, and it inspired countless ports, clones and spin-offs in the 1980s and beyond.

“Written years earlier, Leedom’s letter documents a context and a form of engagement with computer games quite different from today’s popular videogames. Here, the game’s underlying code is necessarily exposed to the user, who must type it in by hand; gameplay takes place not in the living room but in the interstices of military projects’ downtime; and the authorship of the game itself is distributed amongst players who write, rewrite, copy and modify code. The game described by Leedom points to a mismatch between the space-age fantasies of Star Trek and the realities of computing in the 1970s, but it also inspires questions about the historical conditions that gave rise to today’s gamers.”