Harold L. “Hal” Kahn, a professor emeritus of history who taught at Stanford for over 40 years, died at his home in San Francisco on Dec. 11 of natural causes. He was 88.

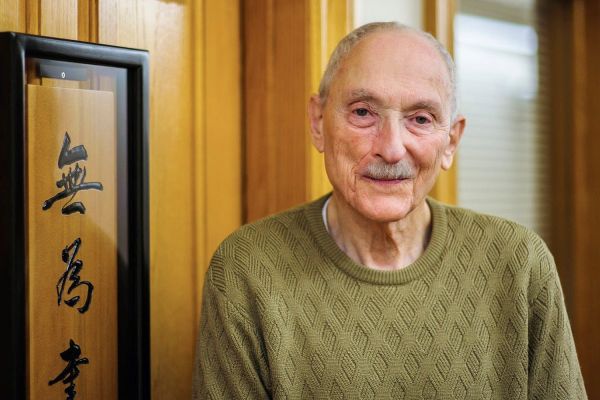

Harold Kahn, who died Dec. 11, helped distinguish Stanford’s History Department for its scholarship in East Asian studies. (Image credit: George Qiao)

Kahn, a specialist in 17th- and 18th-century Chinese history, was known for his engaging teaching style and sense of humor and for his loyalty toward everyone in his life, according to family members and colleagues.

“He was a true intellectual,” said Terry L. Karl, professor of political science and Kahn’s longtime friend and neighbor. “He never owned a TV set, and he read more than anyone I know. He was incredibly witty and just a wonderful human being, deeply caring of his friends and family.”

A generous mentor, inspiring colleague

Originally from Poughkeepsie, New York, Kahn earned a bachelor’s degree from Williams College and master’s and doctoral degrees from Harvard University. He taught history at the University of London before joining Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences in 1968.

Together with history Professor Lyman Van Slyke and Professor of Chinese Albert Dien, Kahn helped distinguish Stanford’s History Department for its scholarship in East Asian studies, creating a generation of leading U.S. scholars in Japanese and Chinese history.

Kahn was especially known for his witty, rigorous style of teaching and his detailed letters of recommendation. He received the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in 1986.

“Hal was a lively, energetic and inspiring professor,” said Gordon Chang, professor of American history, who took some of Kahn’s courses as a graduate student at Stanford. “I will always remember him being there for me as a friend and someone I could consult with about anything.”

Kahn inspired others around him with his dedication to students.

“Hal put so much into the teaching and training of his graduate students,” said Estelle Freedman, professor of United States history. “He was one of the most generous people I’ve ever met. He was more than a mentor. He was a teacher, uncle, advice-giver. I learned a huge amount from the way he worked with students.”

Freedman said Kahn would routinely help students outside his field and open his home to those who couldn’t go home for the holidays. For several decades, almost every Thanksgiving, Kahn would prepare pies, turkey and numerous dishes by himself and invite students, family and friends.

“It was wonderful to witness the joy he took in feeding all those people,” Freedman said.

As a scholar, Kahn dived deep into archival resources as part of his research, which was unusual among Chinese historians at the time, Chang said. Kahn’s 1971 book, Monarchy in the Emperor’s Eyes: Image and Reality in the Ch’ien-lung Reign, won the Commonwealth Club First Book prize.

After Kahn retired in 1998, the Department of History honored his achievements by creating the Kahn-Van Slyke Award for Graduate Mentorship and the Harold Kahn Reading Room, which contains a part of Kahn’s library.

Anti-war advocate

Aside from his teaching and scholarly work, Kahn was passionate about anti-war activism and justice. During the 1970s, he spoke regularly against the Vietnam War.

Chang remembers marching with Kahn in several on-campus anti-war protests.

“I admired his feistiness,” Chang said. “He thought it was very important to not just be informed about the past but also to not be apathetic about current events and politics.”

Karl, who carpooled with Kahn to Stanford from San Francisco for about 40 years, said she and Kahn would often discuss morality and the ethics of war.

“He was a perpetual radical,” Karl said. “He always asked why the government is doing what it’s doing. He saw that questioning to be a big part of his job as an intellectual.”

Friends and family underscored Kahn’s unique, imaginative nature and love of new experiences and people. During one sabbatical, he went to New York to drive a taxi for a year.

His daughter, Stanya Kahn, recalled the weird, funny and inventive bedtime stories Kahn made up for her and her sister, Annika Kahn. Now a Los Angeles-based video artist, Stanya Kahn said her father’s creative thinking, his love of language and ability to see humor in almost anything has deeply influenced her and is reflected in her art practice.

“He was my core person,” she said. “He was erudite and also funny. He was endlessly curious about the world and taught me a real openness to people and their differences. He had a care for humanity that wasn’t just an intellectual one. He really liked to experience cultures and people from across the world and to connect.”

Kahn also enjoyed sports, including running, swimming and playing tennis. He loved backpacking and cooking so much that he co-authored several books on those subjects, including The Camper’s Companion and Backpacking: A Hedonist’s Guide.

“My dad broke out of the box on all levels, whether it was in his writing, his teaching style or the way he raised my sister and I,” said Annika Kahn. “He taught us how to be critical thinkers and to never limit ourselves in what we could achieve in life.”

Annika Kahn, who owns a global martial arts–based fitness company, said her career path was heavily influenced by traveling alongside her father in Asia when she was young. She fondly recalled her father’s patience and encouragement as he taught her at 6 years old how to use chopsticks on one of those trips.

“My dad was selfless and deeply caring for friends and family,” she said. “Even the night before he died, he was still looking after everyone, making sure everyone is going to be OK.”

Kahn is survived by his daughters, Annika and Stanya Kahn, grandsons Kourosh Kahn-Adle and Lenny Dodge-Kahn, sister Muriel Lampell, and his life partner, Maureen McClain.

A memorial to honor Kahn’s life will be held at 10 a.m. on Feb. 9 in Levinthal Hall at the Stanford Humanities Center.

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu