For the past 40 years, a Stanford alumna’s journalistic legacy from the Korean and Vietnam wars has sat forgotten in musty boxes in a basement in Sweden.

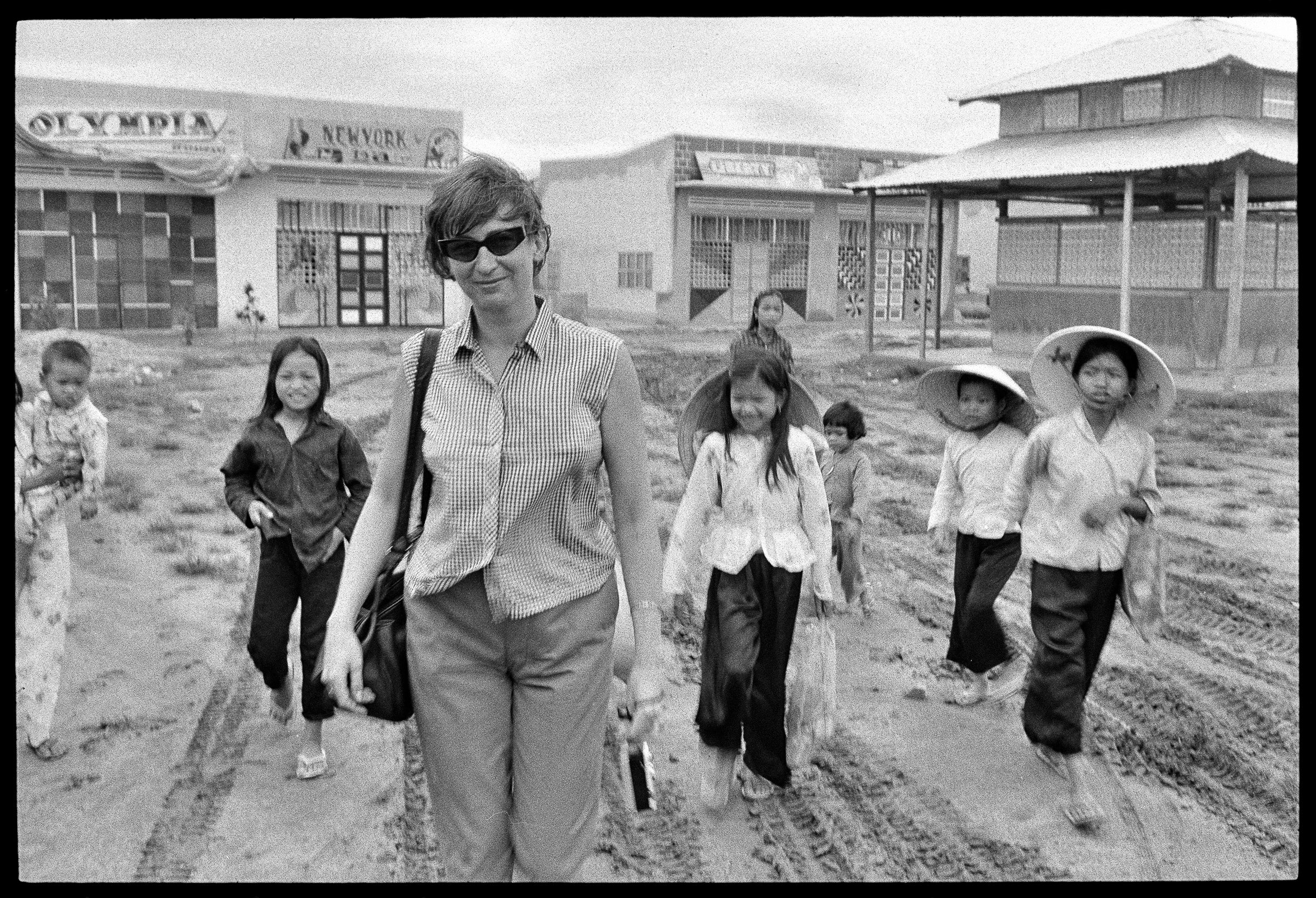

Overseeing Overseas Weekly’s Pacific edition was Ann Bryan, the only female editor in chief in Saigon. She successfully sued the Department of Defense to lift a ban that prohibited women from reporting in combat zones. South Vietnam, 1967 (Image credit: Ann Bryan)

But now, thanks to a new collection at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, the long-lost story about Overseas Weekly – a small tabloid publication that offered an alternative perspective to official military publications – is being brought to light in an exhibition now on display at the Herbert Hoover Memorial Exhibit Pavilion.

In addition to showcasing long-forgotten images, the show highlights the two women who ran the publication, Stanford alumna Marion von Rospach and Ann Bryan, as well as their team of photojournalists who championed freedom of the press and challenged the conventional role of women reporting war on the battlefield.

When exhibit curator Lisa Nguyen saw the photos for first time, she said she immediately was struck by these intimate portraits of soldiers and Vietnamese civilians immersed in the daily life of the war-torn nation.

“Immediately you see the figures, scenes and facets of that period,” Nguyen recalled. “You see the emotions captured on the faces of soldiers and civilians. You see both the fear but also moments of happiness. You also see the moments in between.”

Discovering a long-lost legacy

Some 20,000 images taken for Overseas Weekly have been boxed away in a Nordic cellar of one the former photographers, Calle Hesslefors. After Hesslefors passed away in 2009, the collection made its way to Swedish designer Mark Goldsworthy, who reached out to the Hoover Institution when he realized its historical significance.

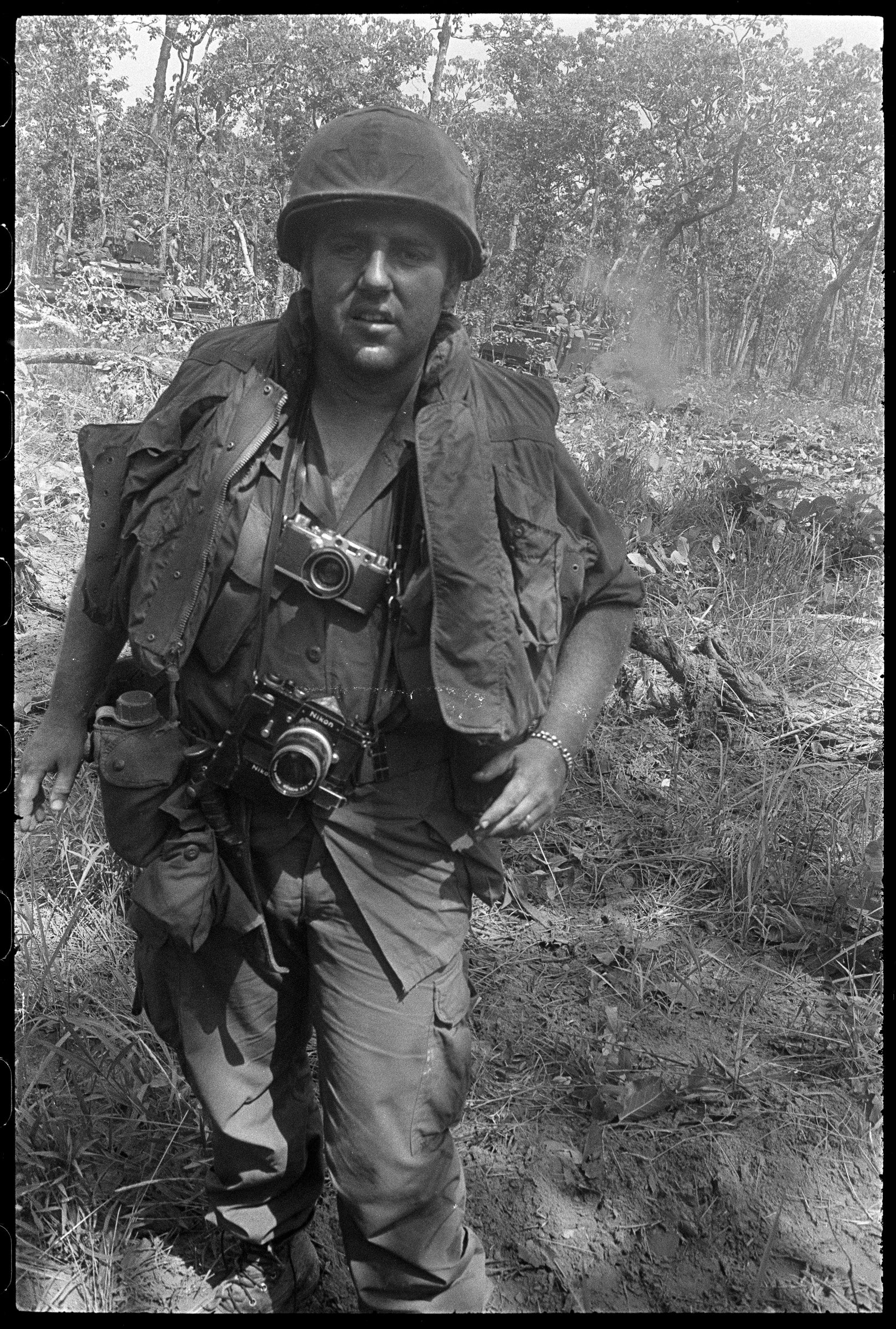

Don Hirst, Overseas Weekly reporter and Pacific Bureau chief (1972-73). Cambodia, 1970 (Image credit: Overseas Weekly staff)

“We welcomed the collection,” said Nguyen, who is the curator for digital scholarship and Asian initiatives at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives and editor of the exhibition catalog and companion book.

But Nguyen also had many questions. When the collection came to her, many of its negatives were warped and deteriorating. Some of the images had no descriptions and were often unattributed.

“We quickly began to wonder, who took these photographs? What circumstances led them to Vietnam – on the battlefield and off? Where are they now?” Nguyen asked.

With little to no information online, Nguyen and her colleagues pored over microfilm reels of old newspapers, traced primary sources and connected to veteran networks to identify photos and learn more about the near-forgotten publication.

Through the State Historical Society of Missouri, where Bryan’s papers are now stored, Nguyen tracked down some of the the photojournalists and reporters, including Cynthia Copple, Art Greenspon, Don Hirst and Brent Procter – whose photos are also included in the exhibition.

“It was incredible,” said Nguyen about reconnecting with them. “You never know how people are going to react. Some were ecstatic – like Don Hirst – who didn’t realize that these photographs had survived.”

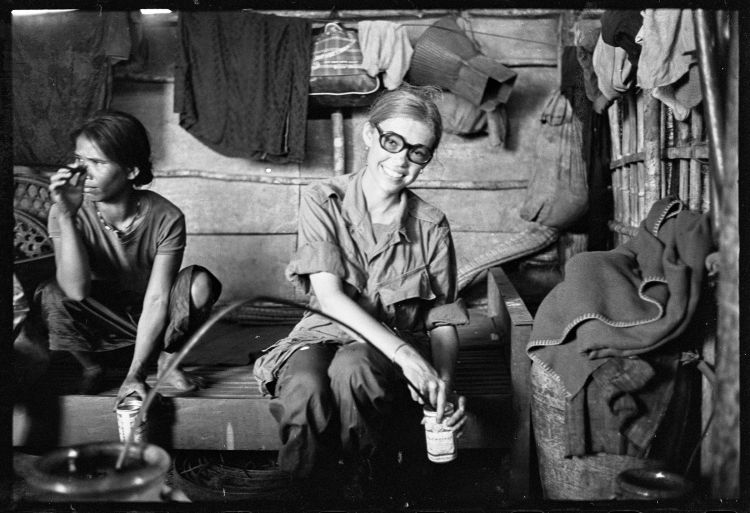

Overseas Weekly freelancer Cynthia Copple sits with a Montagnard family inside a longhouse. Chu Kuk hamlet, 1969 (Image credit: Overseas Weekly staff)

Pvt. 1st Class Danny Pratti, 21 (left), and Pvt. 1st Class Freddie Bradshaw, 20, both from A Company, 4th Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, are picked up by a chopper in the field. Quế Sơn, 1968 (Image credit: Art Greenspon)

Reporting on the Vietnam War

The exhibition focuses on the Overseas Weekly operation during the Vietnam War, when it covered controversial topics such as racial prejudice within the ranks, pot smoking among the troops and courts-martial. In addition to reporting hard-hitting news, the paper was also known for its humor and a titillating centerfold that earned the tabloid the nickname “the Oversexed Weekly.”

In addition to covering topics that didn’t fit the Pentagon’s point of view, the publication flouted norms about women covering wars.

During that time, Bryan was the only female editor in chief in Saigon and went head to head with the Pentagon not once but twice.

At one point, Overseas Weekly was prohibited from being sold at military newsstands, but the ban was lifted after several U.S. congressmen, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Hearst Corporation helped intervene.

Bryan also successfully sued the Department of Defense to lift a ban that prohibited women from reporting in combat zones, allowing for women like Cynthia Copple – whose work is also on display in the exhibition – to report from the frontline of conflict.

“This story is very topical now,” said Nguyen. “As freedom of the press is being questioned, whose story do you tell? It’s all very relevant to today’s society.”

For Fred Tuner, a professor of communication at Stanford and author of Echoes of Combat: The Vietnam War in American Memory, it was remarkable to see how much access these journalists had with the troops.

He said he was also struck by how the images on display show the soldiers as ordinary people in extraordinary situations.

“This was a time when soldiers were all of us, not just a specialized volunteer force,” said Turner, alluding to the U.S military draft that saw 2.2 million American men between 1964 and 1973 conscript into service.

Turner, who is the Harry and Norman Chandler Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, has also been involved with the exhibition: In June 2018 he moderated a panel discussion with Copple.

A cyclist pedals through the barren streets of Qui Nhon, which was ordered off limits to American soldiers due to racial violence among military police. (Image credit: Tom Marlowe)

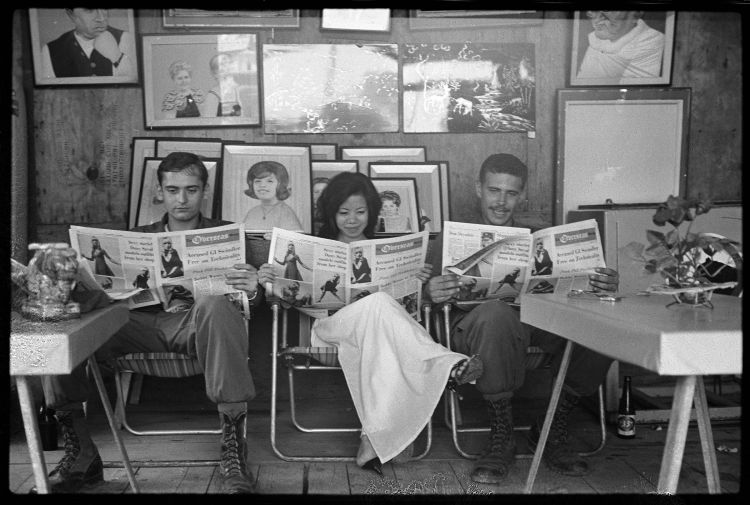

Readers of the Overseas Weekly, Pacific Edition. South Vietnam, 1968 (Image credit: Phil Jordan)

A new audience

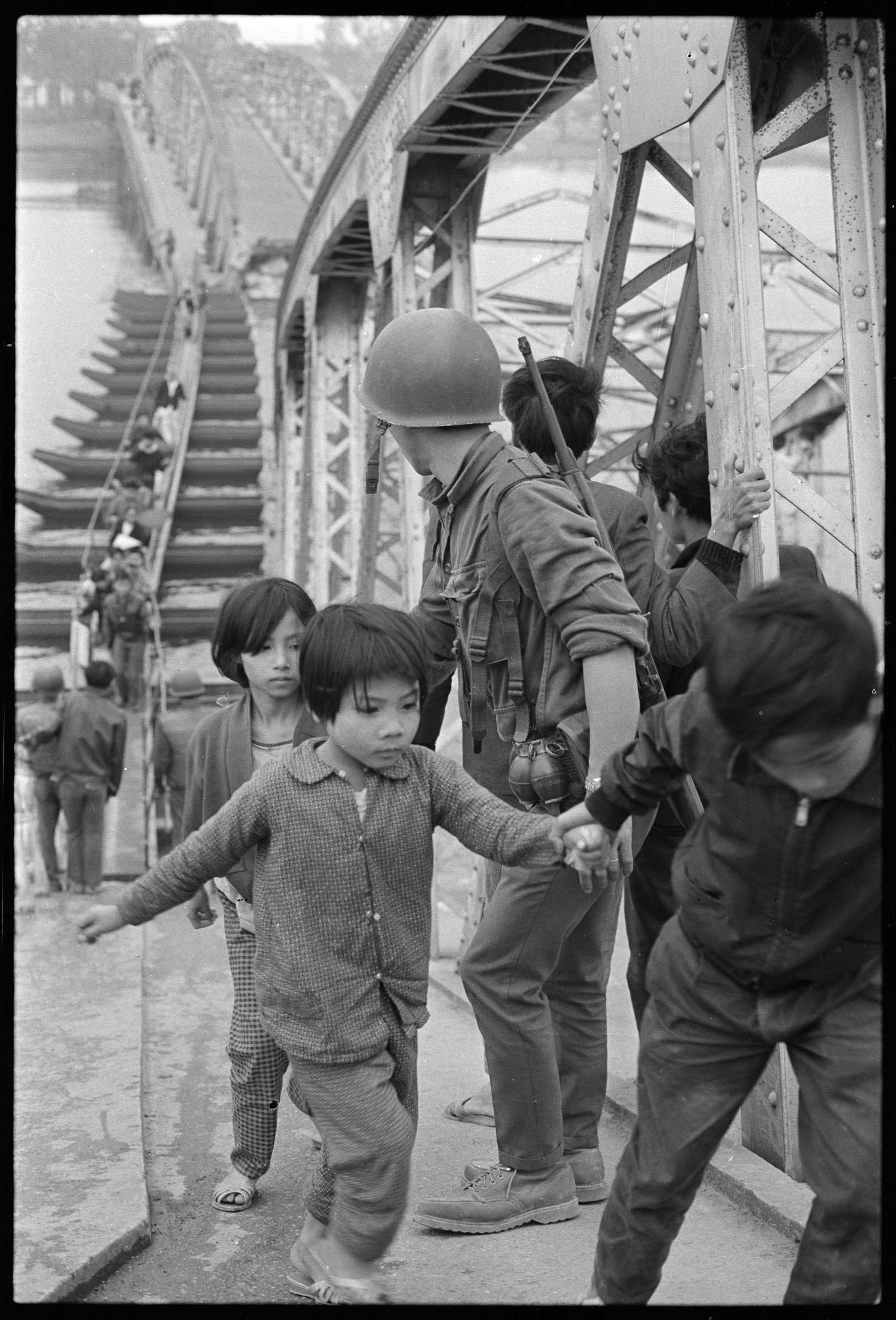

Refugees flee from the northern side of the Perfume River. March 1968 (Image credit: Art Greenspon)

In addition to featuring the everyday lives of the American military in Vietnam, many photos depicted their daily interactions within the community.

Nguyen hopes this exhibition will resonate with new audiences, including many Vietnamese Americans who immigrated to the United States after the war. Their story has yet to be fully told, said Nguyen.

“There is a Vietnamese community who lost their country and to see their stories brought to light is also important,” said Nguyen. “This is a very politicized, emotional time period for them. And their images don’t get to be seen very often.”

The exhibition, “We Shot the War: Overseas Weekly in Vietnam,” runs through Dec. 8 (closed Nov. 22 and 23). The exhibition is open to the public, free of charge, Tuesday through Saturday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. in the Herbert Hoover Memorial Exhibit Pavilion, next to Hoover Tower, on the Stanford University campus. Parking on campus is free on Saturdays. For directions and parking, visit the Hoover Library and Archives website.