Can a work of art be erotic without directly mentioning sex or sexuality? According to Claire Jarvis, a professor of English at Stanford, novelists in Victorian England mastered the art of building erotic tension without uttering a word about sex itself.

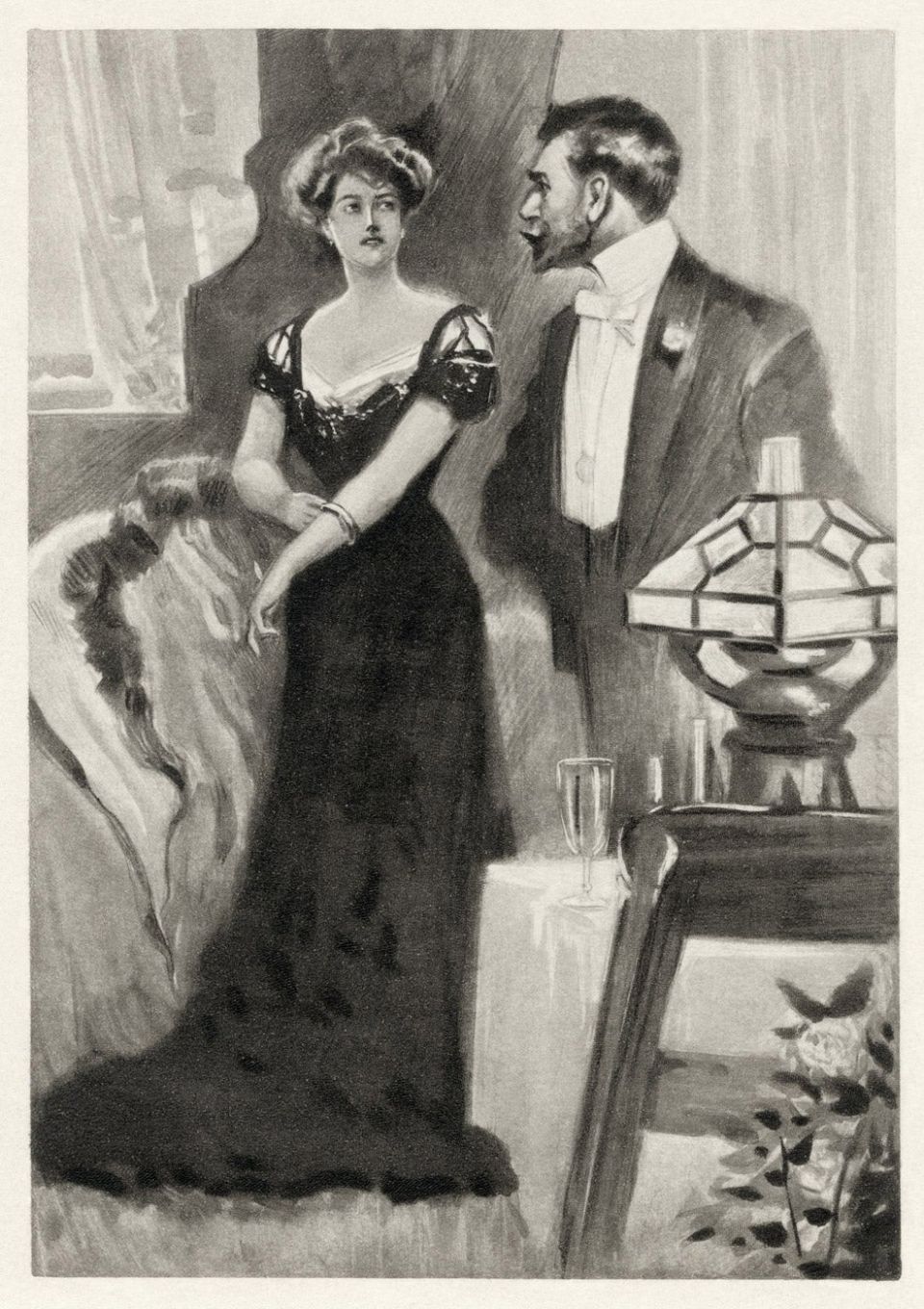

Sexual tension is indicated obliquely in Victorian novels, but novelists found ways around societal strictures. (Image credit: Wikipedia)

They achieved this by planting a recurring type of character – the “dominant woman” – in scenes of ornate description.

“It’s not that people in the 20th century invented the representation of sex,” Jarvis said. Rather, “the respectable novel didn’t show sex within its pages until the 20th century. Victorian novels had to find ways to build erotic tension without using explicit language.”

By “dominant,” Jarvis means “sexually aggressive female characters” – or, as she explained, “women who seemed to be imperious, who challenged the traditional marriage plot and who were in some ways the early version of a femme fatale.”

Jarvis’ book, Exquisite Masochism: Marriage, Sex, and the Novel Form, finds that dominant women often appear in erotically charged scenes. Scenes of this sort frequently have “masochistic” overtones with sexual desires left unfulfilled or denied outright.

By disguising eroticism as ornate description, turn-of-the-century novelists could hint at sexual frustration without coming too close to explicit depiction. Such masochistic scenes occur in the novels of Emily Brontë, Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence and Anthony Trollope.

Erotic aesthetics

Novels that portrayed sex in the open would run afoul of contemporary sensibilities. Therefore, “indirect allusion” was a necessary device in Victorian literature. Authors watched their words, favoring methods that allowed them to “represent sexuality as important to thinking about marriage, but not painting or inflecting the central marriage plot with an unseemly sexuality, ” Jarvis said.

For Jarvis, seemingly innocuous passages could “build sexual tension without directly challenging traditional romantic or marital structures within their society.” “This,” she added, “was a way of presenting potent sexual allure without jeopardizing the central domestic, bourgeois-world-building marriage of the Victorian novel.”

Jarvis sees a uniquely Victorian eroticism in a passage from Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) when the servant Nelly Dean finds Heathcliff, the novel’s romantic hero, mesmerized by what is apparently the ghost of his former lover, Catherine.

As Brontë writes, Heathcliff’s face “communicated, apparently, both pleasure and pain in exquisite extremes: at least, the anguished, yet raptured, expression of [Heathcliff’s] countenance suggested that idea.” For Jarvis, tension between opposing sensations epitomizes the “exquisite masochism” of sexuality in turn-of-the-century England.

Victorian authors relied on all manner of innuendo to hint at erotic acts, said Jarvis, for whom “extreme attention to aesthetic detail” is “one of the key elements of the sexual, masochistic scene.” Hefty description slows the pace of action, allowing for the buildup of sexual tension between characters. “If you are reading a novel and all of a sudden the description becomes extremely ‘thick,’ you may be in the middle of an erotic scene.”

According to Jarvis, descriptive passages “freeze” the plotline’s action, which builds tension and “gives us a way of understanding what is happening in those erotic scenes that may have been harder to explain otherwise.”

For example, in Phineas Finn (1869), Trollope narrates Finn taking leave of lady Madame Max in fine detail. Nothing goes unsaid. The cozy appearance of the room, the scene outside the windows, Madame Max’s peculiar clothes – everything is accounted for, maximizing sexual tension through allusion. Frustrating for readers and characters alike, Trollope suspends the plot’s action, hinting at a potential liaison between the characters.

Beyond ideology

In Exquisite Masochism, Jarvis takes on another tension: a trend in literary studies where older texts “are read with the goal of only answering contemporary historical and political questions.”

An alternative way of reading old literature is to imagine how the author would have read it – as Jarvis put it, “to see the texts in their own terms and to think about how our current political or social positions might inflect the way we read them.”

Like other works of art from centuries past, Victorian novels might offend contemporary readers, a case in point being the overt sexism and racism in D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love (1920).

“Some novels I am working on – especially those by Anthony Trollope and D.H. Lawrence – have been read as explicitly anti-feminist, and they are indeed very problematic. It is easy to write them off as politically repugnant and leave them at that,” Jarvis said.

“What is going on here is more than just misogyny. This isn’t to say that we should read apolitically, but if we read only with an eye to an explicit political aim, we can miss out on the complexity and beauty that these novels actually have.”

Not ignoring politics altogether in Exquisite Masochism, Jarvis shifted her focus from a strictly sociopolitical reading to the structural and formal techniques of the authors. Studying these quickly led to her to realize that sex and eroticism “are actually central to Victorian aesthetics, and they are everywhere in the Victorian novel.”

When reading beyond ideology, she said, “we see just how deeply the Victorian novel is invested in representing sexual life.”