Rio de Janeiro, site of the upcoming Summer Olympics, is firmly in the public eye.

With controversy surrounding preparations for the games, impeachment proceedings looming against President Dilma Rousseff and threats from the Zika virus, it is a symbol of Brazil’s larger instability.

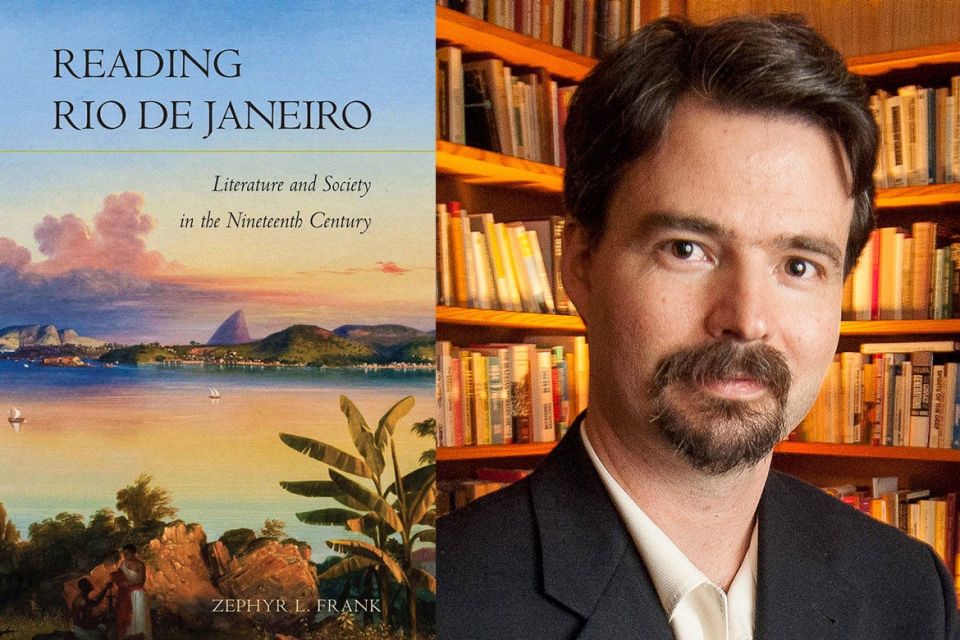

Stanford history Professor Zephyr Frank used up-to-date methods of digital analysis to explore 19th-century life in the Brazilian city hosting the 2016 Summer Olympics for his book Reading Rio de Janeiro. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

That has led one Stanford scholar to look back in history to uncover the complex social foundations of the contemporary city.

“Many of the challenges facing citizens today, such as access to housing, public health and education, have their foundations in the 19th century,” said Zephyr Frank, professor of history and former director of the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis at Stanford.

In his latest book, Reading Rio de Janeiro, Frank combined his historical vision with literary analysis, finding that the story of Rio’s social history played out in much of the literature of the late 19th century.

“This was a cityscape defined by great inequalities in wealth and power,” Frank said. “It was a world that distrusted politicians and their motives, a place where financial capital had recently come into the ascendency and where people were trying to make it in the big city.”

According to Frank, well-known novels of the 1870s and 1880s remain unsurpassed as interpretations of what it means to grow up and confront the intensity and complexity of the metropolis.

“It was a time when the blueprint for the contemporary city was created,” he observed.

For all that it has changed since then, there is much to learn from the literary representations of that period.

Frank’s perspective, a blend of literary and historical analysis, was inspired by reading the works of Machado de Assis (1839-1908), Brazil’s literary master and one of the great modern writers.

“Machado’s prose slashed through the pretense of the rich and the wellborn in 19th-century Rio de Janeiro,” Frank said, adding that he found in his literature vital material for a thorough investigation of the Brazilian zeitgeist set in Rio.

Reading Rio

To complement his literary research, Frank also collected thousands of estate inventories and many more thousands of parish records in order to juxtapose the stories in the novels with archival evidence.

“I did this not in order to check the veracity of the novels, though this was of some interest to me, but primarily to aid my understanding of the history embedded in the literature,” Frank said.

Frank centered his research on this period as it marked an important historical juncture. During the second half of the 19th century, the economy of Rio substantially changed.

After 1850, Frank said, a series of legal reforms opened the way for a deepening of capitalist development. The underlying structure of society shifted, with a rise in financial wealth and a concomitant decline in the role of slavery in the city.

During this period, the banking and finance industries grew, as did the city population, and Rio cemented itself as the economic and cultural center of Brazil. These changes generated a societal shift for younger generations of urban dwellers.

Frank wanted to understand how those changes in the financial and social world of the city manifested in cultural attitudes.

“How did novelists explain the significance of these transformations?” he wondered. “For some novelists, such as José de Alencar, these changes were interpreted with anger as threats to the social order and for others, like Machado de Assis, there was ironic detachment from the new way of life.”

From that basis, Frank was able to explore how fictional characters existed in the midst of so much turbulence.

“What did they say, where did they go, how did they take positions and navigate through this dynamic cityscape? Novels helped me answer these questions through both close readings of particular scenes and semantic fields as well as through a more distant reading of spaces and networks,” Frank said.

Visualizing literature

For a historian working with literature, Frank wrestled with the question of what to do with his observations on novels of the time – especially those of Machado de Assis.

The defining moments of the project came through his research collaborations with two Stanford labs, inspiring him to adopt digital techniques to elaborate his historical and literary picture.

“At the Spatial History Project, and particularly the Terrain of History project, we developed the relationship between literature and history,” said Frank, noting that “a digital picture of 19th-century Rio de Janeiro emerged.”

That prompted Frank to map the action in several key novels from the Brazilian canon, including de Assis’ work and other authors such as José de Alencar and Aluísio Azevedo.

Frank then plotted notable scenes and events of the narratives on a digital city map. He shared his literary maps and diagrams with the Stanford Literary Lab, which inspired him to develop the analysis into a book about social integration in the city.

“That gave me the insight to see literary materials in a more expansive light. It united what had previously been a series of unrelated observations about the roots of inequality in Rio de Janeiro,” said Frank. “I then found that novels could provide me, a historian, with more than just ‘local color’ about a place and pithy quotes.”

In Frank’s book, he argues that novels provide a coherent, even forensic, model of society, offering unparalleled insight into everyday life in bygone times.

In his words, “I focused on realistic coming-of-age novels, and they each mapped diverse stories of social integration, of finding one’s way in the complex metropolitan world, at a vital historical juncture.”

Although fictional, Frank concluded, these narratives play into a realistic representation of life and offer a coherent depiction of the roots of Rio de Janeiro, the underpinnings of today’s Olympic city.

Media Contacts

Chris Kark, director of humanities communication: (650) 724-8156, ckark@stanford.edu