Stanford researchers are developing a machine for designing better contact lenses.

When contact lenses work really well, you forget they are on your eyes. You might not feel the same at the end of a long day staring at a computer screen. After too many hours of wear, the lenses and your eyes dry out, causing irritation that might outweigh the convenience of contacts.

Stanford researchers hope to alleviate this pain by both advancing the understanding of how natural tears keep our eyes comfortable, and developing a machine for designing better contact lenses.

The work was inspired in part by a graduate student’s dry eyes.

“As a student, I had to stop wearing lenses due to the increased discomfort,” said Saad Bhamla, a Stanford postdoctoral scholar in bioengineering who conducted the work as a graduate student in Gerald Fuller’s chemical engineering laboratory at Stanford. “Focusing my PhD thesis to understand this problem was both a personal and professional goal.”

Bhamla isn’t alone. More than 30 million Americans currently wear contacts, but roughly half of them switch back to glasses because of contact lens-induced symptoms such as dry eye. Bhamla and Fuller suspected that most of the discomfort arises from the break up of the tear film, a wet coating on the surface of the eye, during a process called dewetting. They found that the lipid layer, an oily coating on the surface of the tear film, protects the eye’s surface in two important ways – through strength and liquid retention. By mimicking the lipid layer in contact construction, millions of people could avoid ocular discomfort.

In their most recent study, Bhamla and his co-authors outline two functions of the lipid layer. One is to provide mechanical strength to the tear film. Lipids in this layer have viscoelastic properties that allow them to stretch and support the watery layer beneath them.

Bhamla likens this protective lipid layer to a swimming pool cover. You can’t run on the open water, but even a thin tarp can provide mechanical strength to support a person’s weight.

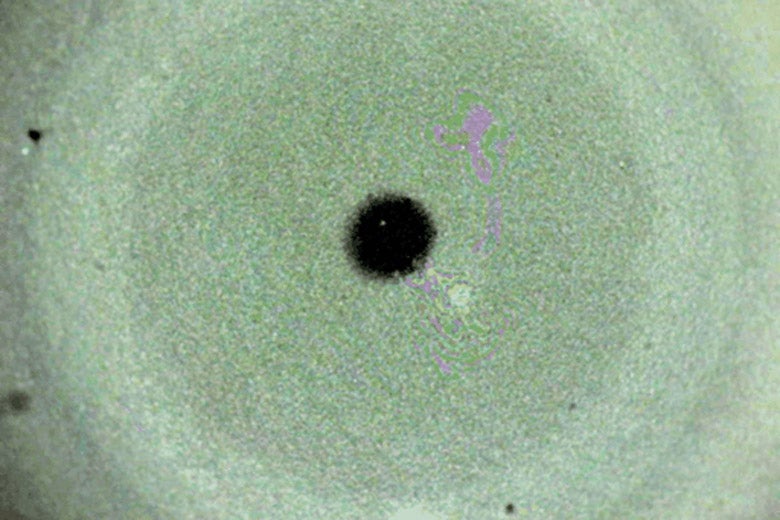

Using the i-DDrOP device, researchers can observe how a tear dissolves. (Image credit: Courtesy Saad Bhamla)

“You will sometimes see the guards at the Stanford Avery pool run over the surface of the covered pool,” Bhamla said. “The mechanical structure is very thin, but it protects the whole bulk of the liquid. If the swimming pool is shrunk to 1/100th the width of a hair, it is a good representation of the tear film with a lipid layer replacing the tarp.”

The lipid layer also prevents the tear film from evaporating away. Eyes are roughly 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius), which is usually warmer than the ambient air. Like any liquid on a hot surface, the eye is constantly heating its liquid coating and losing moisture to the air.

“We recognized early-on that the fluid mechanical responses of the lipid layer were just as important as the conventional view that its role was to control evaporative loss,” Fuller said. “And it’s been gratifying to realize that the combined role of these two forces is now accepted.”

The key to producing comfortable contact lenses, then, involves designing lenses that don’t destabilize the tear film. Manufacturers recognize the importance of protecting the eye’s natural tear film on a contact lens surface to minimize painful symptoms such as dry eye, but it is not an easy thing to measure.

“Some people are studying contact lenses by holding them up to a light, dipping them in water, and looking at them to see if the tear film breaks up,” Bhamla said. “We felt we could definitely do better than that.”

To solve this, Bhamla and Fuller built a device that mimics the surface of the eye. The machine, called the Interfacial Dewetting and Drainage Optical Platform or i-DDrOP, reproduces a tear film on the surface of a contact lens. It allows both scientists and manufacturers to systematically handle the unique array of variables that affect the tear film, including temperature, a variety of substances, humidity and the way gravity acts along a curved surface.

With the ability to accurately recreate a tear film on the contact lens surface and test how quickly it breaks up, manufacturers are now armed with the tools to make a more comfortable lens that protects users from the painful side effects of wearing contacts. Even Bhamla may trade in his glasses for a new pair of lipid-protected eyewear.

This study was co-authored by Chew Chai, Noelle Rabiah and John Frostad from Chemical Engineering at Stanford.

Media Contacts

Saad Bhamla, Bioengineering: bhamla@stanford.edu

Bjorn Carey, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-1944, bccarey@stanford.edu