In the decades following the work by physiologist Ivan Pavlov and his famous salivating dogs, scientists have discovered how molecules and cells in the brain learn to associate stimuli, like Pavlov’s bell and the resulting food. What they haven’t been able to study is how whole groups of neurons work together to form that association. Now, Stanford University researchers have observed how large groups of neurons in the brain both learn and unlearn a new association.

“It’s been over 100 years since Pavlov did his amazing work but we still haven’t had a glimpse of how neural ensembles encode a long-term memory,” said Mark Schnitzer, associate professor of biology and applied physics, who led the research. “This was an opportunity to examine that.”

The researchers worked with mice and focused on the amygdala, a part of the brain known to be involved in learning that is extremely similar across species. They taught mice to associate a tone with a mild shock and found that, once the mice learned the association, the pattern of neurons that activated in response to tone alone resembled the pattern that activated in response to the shock. Using Pavlov’s dogs as an analogy, this would mean that, as the dogs learned to associate the bell with the food, the neural network activation in their amygdalas would look similar whether they were presented with food or just heard the bell.

The researchers’ results, published in Nature on March 22, also reveal that the neurons never returned to their original state, even after the training was undone. Although this was not the main focus of the study, this research could have wide-ranging implications for studying emotional memory disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Building on Pavlov’s work

The researchers trained mice in the study to associate a tone with a light foot shock. At the beginning of the experiment, mice had no reaction to the tone, but would freeze in place in response to the light shock. After pairing the tone and the light shock a few times, the tone alone was enough to cause the mice to freeze in place.

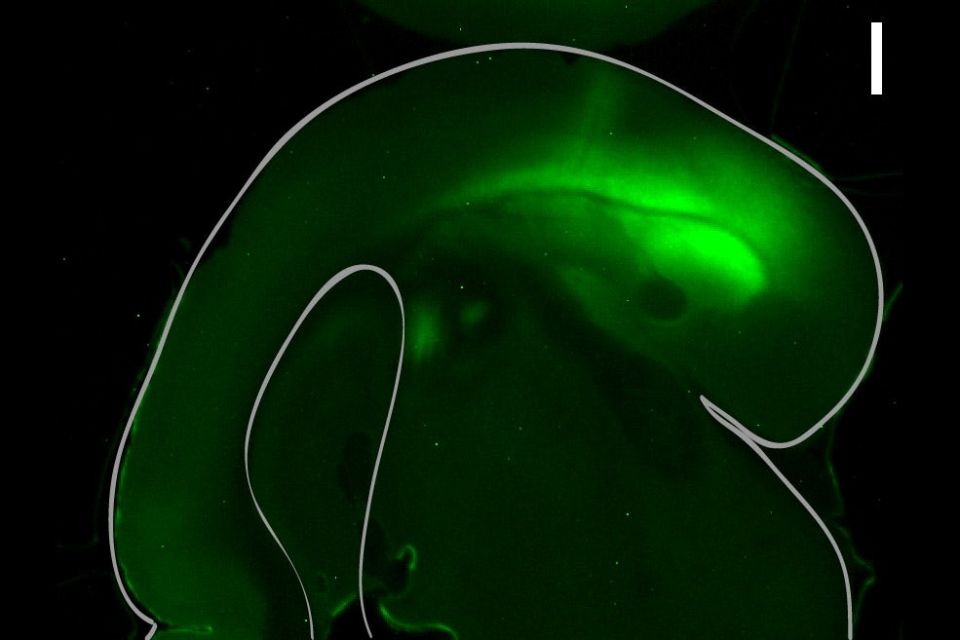

Neurons from the amygdala in this mouse brain slice have been stained so that researchers could measure the activity of the neurons. (Image credit: Benjamin Grewe)

“You can think of this type of learning as a survival strategy,” said Benjamin Grewe, lead author of the paper and former postdoctoral scholar in the Schnitzer lab. “We need that as humans, animals need that. When we associate certain stimuli with their possible dangerous outcomes, it helps us to avoid dangerous situations in the first place.”

During the training, the researchers directly observed the activity of about 200 neurons in the amygdala. Using a miniature microscope – developed previously by the Schnitzer lab – to view neurons deep in the brain, they could observe activity of individual cells as well as of the entire ensemble. What they found was that, as the mice learned to associate the tone with the shock, the set of cells that responded to the tone began to resemble those that responded to the shock itself.

“The two stimuli are both eliciting fear responses,” said Schnitzer, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “It’s almost as if this part of the brain is blurring the lines between the two, in the sense that it’s using the same cells to encode them.”

The amount of change in how the group of neurons responded to the tone also predicted how much the mouse behavior would change. Mice whose amygdalas activated similarly in response to the tone and to the shock froze most consistently in response to the tone, by itself, 24 hours later.

“We managed, for the first time, to record the activity of a large network of neurons in the amygdala and did that with single cell resolution,” Grewe said. “So we knew what every single cell was doing.”

Lingering associations

As part of the experiments, the team also undid the conditioning so that the mice stopped freezing in reaction to the tone. During this phase the neural response never completely returned to its original state.

The experiment to reverse the association was not designed to represent any human diseases or disorders, but this finding could potentially inform research into problems with emotional memory, such as generalized anxiety disorder or PTSD, where people may have difficulty dissociating neutral stimuli from negative ones. That kind of application, however, would likely be some years in the future.

“We’re just beginning this work,” Schnitzer said, “but these findings give us a window into how the external world may be annotated for us in this brain structure.”

Additional co-authors of this work include Lacey J. Kitch, Jerome A. Lecoq, Jesse D. Marshall, Margaret C. Larkin, Pablo E. Jercog, and Jin Zhong Li of Stanford University and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Jan Gründemann and Francois Grenier of the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research; Jones G. Parker of Stanford University and Pfizer Neuroscience Research; and Andreas Lüthi of the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research and the University of Basel. Schnitzer is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Neurosciences Institute.

This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the U.S. National Science Foundation, Stanford University, the Simons Foundation, the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, the Novartis Research Foundation, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and DARPA.

Media Contacts

Taylor Kubota, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-7707, tkubota@stanford.edu