Maps help us locate landmarks and can even trace historical change.

But can they convey people’s feelings? Or are emotions “unmappable”?

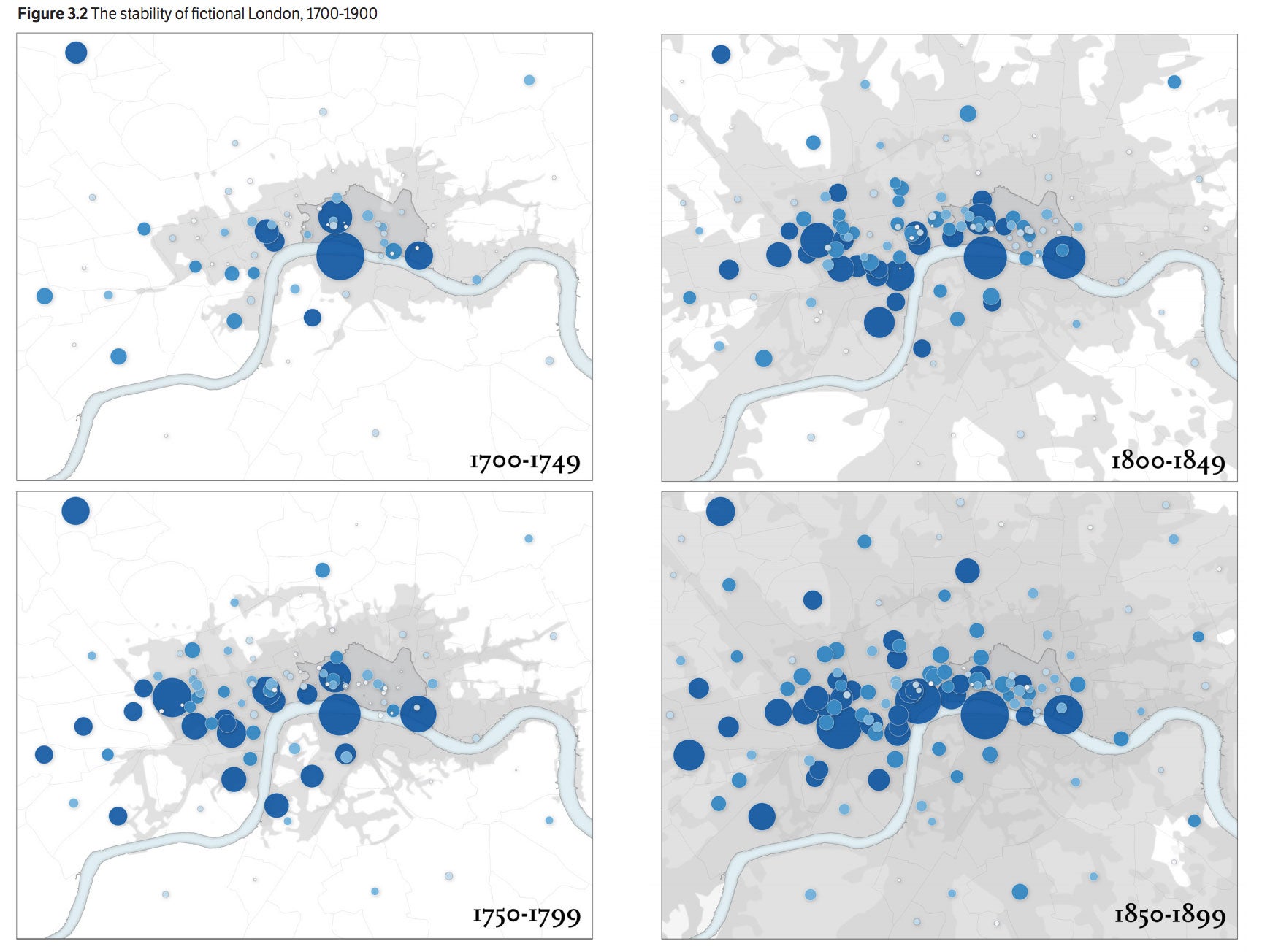

Maps illustrate the fictional stability of London from 1700 to 1899. While London’s actual population increased from 600,000 to 4.5 million during this time, the London depicted in literature remained largely the same: The number of geographical references kept increasing but they remained essentially localized in the City and in the West End. (Image credit: Stanford Literary Lab (CESTA))

A collaboration between Stanford’s Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA) and its Literary Lab offers a solution. The Literary Lab’s newest pamphlet, “The Emotions of London,” illustrates the ways 18th- and 19th-century British novels associate feelings with various parts of England’s capital.

Take, for instance, the stark difference between London’s West End, an enclave for the rich, and the City, a bustling district marked by poverty as well as enterprise. According to Ryan Heuser, a doctoral candidate in English who co-authored the pamphlet, the divide between these neighborhoods registers in the literature of the period as “an emotional binarism between positive [happy] and negative [fearful] affective associations.”

Most readers of the period were members of the middle and upper classes. The way the era’s novels depict real-world locations, such as the impoverished Clare Market, helps us understand how London’s bourgeoisie imagined areas in their city where they would never tread.

Still, for the co-authors of “The Emotions of London,” these literary portrayals are more imaginary than real. The London of 18th- and 19th-century fiction differs markedly from the historical London of the same period. And while novels of the era could be intensely emotional, those emotions are not always associated with the locations named in the study.

London, real and imagined

According to the pamphlet, the population of London exploded between 1700 and 1900, ballooning from roughly 600,000 to more than 4.5 million. During the same period, its physical territory swelled significantly from what was just a strip along the Thames River.

However, the “imaginary” geography of London’s literature stayed much the same, sticking to the West End and to the City. Because of this, the locations employed by England’s earliest novelists, such as Daniel Defoe and Henry Fielding, largely resemble those drawn on by authors throughout the following two centuries. A 19th-century “silver-fork author,” such as Catherine Gore, focused on the upper-crust West End, while the “Newgate novelist” W.H. Ainsworth set his melodramas in the City’s famous prison.

“It is fascinating to measure how novelists both reflect normative space and diverge from ‘real’ space,” said Erik Steiner, co-director of CESTA’s Spatial History Project and the pamphlet’s primary cartographer. “London novels tended to be slow to adopt new places as they were populated over time.”

One reason for this was the unique inertia of London’s well-to-do. Whereas the moneyed classes of Paris and New York tended to move around, affluent Londoners stayed put in the West End through the two centuries in question. The West End’s boundaries, Steiner said, “only somewhat enlarged … to allow for the osmosis of the old and new ruling class.”

The City also remained well represented throughout the period’s literature – although for a different reason. The City’s dense population and variety of industries – such as finance, law, trade and the press – provided authors with ample material to tell an array of stories. So, while a Gothic novelist like Ainsworth might focus on Newgate or the Tower of London, authors like Charles Dickens and William Thackeray told stories situated in the City’s legal and financial districts.

Unemotional city

The researchers used Named Entity Recognition technology, which labels sequences of words in a text, to plot literary references on a map of London.

“The named locations we were searching for, the majority of which are necessarily of public sites,” said Heuser, “might actually dampen the degree of emotionality” as compared to passages that focus on private or interior spaces. Added Heuser, “This surprised us.”

For the period’s literature in general, though, “public places are less emotionally charged than private spaces,” Steiner said.

Despite the pamphlet’s findings on fear and happiness, its co-authors discovered that literary references to specific places often lacked emotion. As a result, they produced “less a map of the emotions of London than of their absence.”

Occasionally, a setting would evoke fear – such as the “bleak, dilapidated street” in Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) – but did not match any real location on the map. The pamphlet suggests that, with the exception of particularly sinister settings such as Newgate Prison, novels relied on “geographic reticence” as a “key ingredient of narrative fear.” Not knowing where something took place, it seems, was enough to send chills down the reader’s spine.

Crowdsourcing and literary mapping

The makings of “The Emotions of London” go back several years, when the Literary Lab began extracting geographic data from a large body of 19th-century novels. The pamphlet took shape more recently when CESTA received a grant from the Mellon Foundation to apply crowdsourcing techniques in the digital humanities.

The grant allowed the Literary Lab to crowdsource readings to freelancers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform. Readers were asked to identify happiness or fear (or their absence) in some 15,000 passages from novels set in London between 1700 and 1900. Their responses were then compared to close readings by graduate students in English and to the findings of a computer program that gauges sentiment.

To date, said Heuser, the study “may be the most comprehensive attempt to unite the quantitative methods of digital literary geography – counting the number of mentions of locations – and qualitative methods of pre-digital literary geography,” whereby scholars like Franco Moretti, professor of English and pamphlet coauthor, examine geography in literature on a smaller scale.

While the pamphlet is a Literary Lab publication, the study itself pooled a variety of resources from across CESTA, notably the Literary Lab and Spatial History Project, with significant contributions from former research assistants Van Tran (BA ’16) and Annalise Lockhart (BA ’14).

“CESTA is built around the idea that we can and should work closely together on meaty challenges,” said Steiner. “So, aside from the work of the lead authors on the project, this was truly a collaborative effort.”

“More collaborations between these labs will undoubtedly arise, for the mutual benefit of all,” Heuser said.

Media Contacts

Christopher Kark, Director of Humanities Communications: (650) 724-8156, ckark@stanford.edu