Stanford’s first major student demonstration occurred during the so-called “Liquor Rebellion.” In 1908, 300 students marched to rebel against a new alcohol ban on campus.

A suspension letter, addressed to a student who partook in the Liquor Rebellion, is one of thousands of archival treasures on display at a new exhibition at Green Library celebrating Stanford’s 125th anniversary. Drawing on a trove of photos, fliers and student publications from the past, Stanford Stories from the Archives: 1891-2016 showcases the unique history of student life on the Farm.

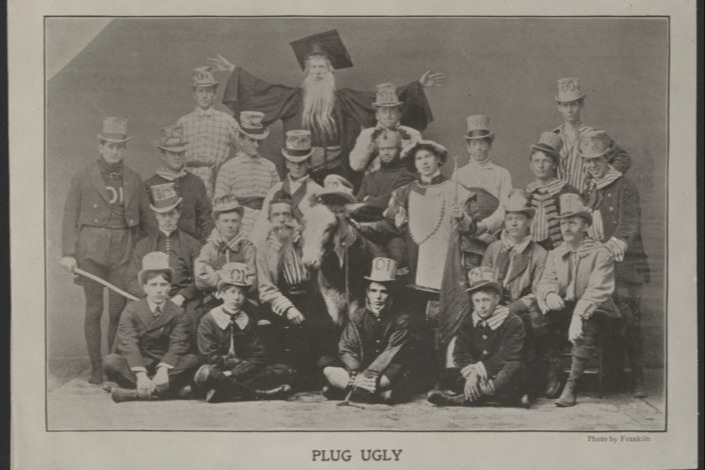

The main exhibition, in the second-floor Bing Wing galleries, has two parts. The first is thematic, devoted to student traditions, activism, housing, overseas study and fieldwork; the second is chronological, capturing student experiences by decade, starting with the Pioneer Class of 1895.

But the exhibition goes beyond chronicling the everyday life of students. “It also shows how the curriculum has changed through the actions and the demands of students and their growing consciousness about equality/inequality, gender, race and ethnic background,” said Becky Fischbach, the designer and coordinator for Stanford Stories.

“It’s often the role of young people to challenge the status quo, and that certainly has been true of Stanford students going way back,” she said.

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

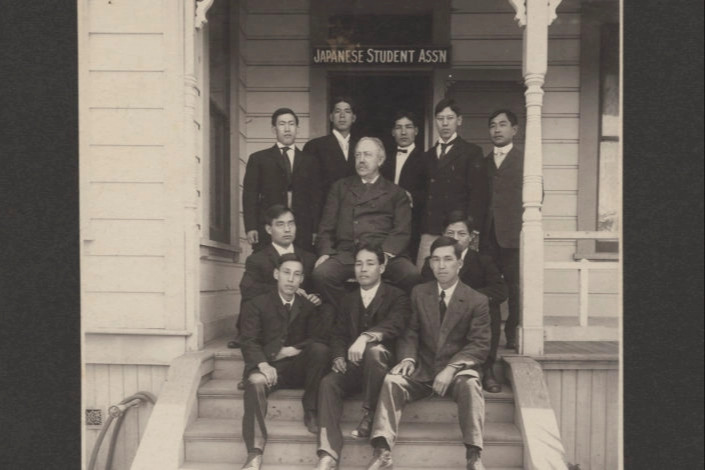

Jordan was an ichthyologist with an interest in Japanese fishes.

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

Image credit: Stanford University Archives

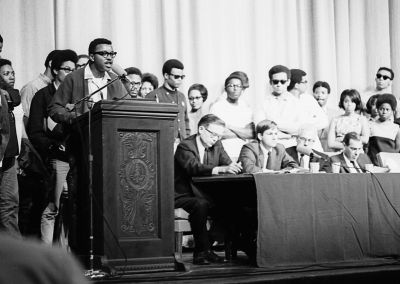

Student activism, then and now

“One of the main things that permeates the exhibit is student activism,” said University Archivist Daniel Hartwig.

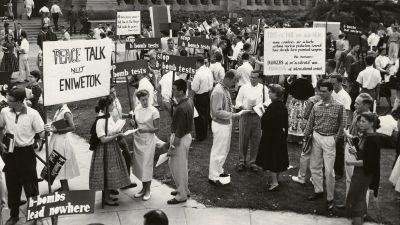

A photograph from 1958, early in the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, portrays a group of around 1,000 students holding anti-nuclear-testing signs in front of the library.

The largest protests in Stanford history erupted during the Vietnam War. One of the exhibited items is a 1968 letter written by Michael Novak, a Catholic theologian and outspoken Vietnam War critic and professor in religious studies from 1965 to 1968. Novak’s letter supported students who occupied the Old Union to protest CIA recruitment on campus.

Exhibition designer Becky Fischbach and University Archivist Daniel Hartwig discuss the placement of the handle to the Stanford Axe in the display case at Green Library. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Fischbach found Novak’s letter particularly moving. “It says that we need to listen to these students; they are the voice of the conscience of this generation. And as educators we should support them,” she said.

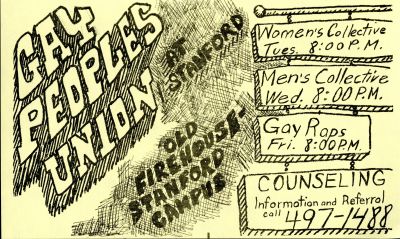

Exhibition materials from more recent decades feature students advocating for the rights of women, Native Americans, the LGBTQ community and victims of sexual assault.

Stanford students have also agitated for racial equality and against racism. For instance, Stanford Stories features a photograph of Dr. Martin Luther King’s first campus visit in 1964, when he spoke at Memorial Auditorium.

Answering Dr. King’s call for action, several students traveled to the South to march on the front lines of the civil rights movement. Stanford’s student-organized radio station, KZSU, initiated Project South, whose members attended and recorded speeches by civil rights advocates. “Dr. King’s message resonated, and continues to resonate, on campus,” Hartwig said.

Before working on the project, Josh Schneider, assistant university archivist, who co-curated Stanford Stories, was unaware that Stanford had such a significant undercurrent of activism.

But Fischbach, a Stanford alumna, was unsurprised. “The whole Stanford community is a community of dialogue, and often heated dialogue,” she said, adding that “students, faculty, staff and administration are constantly involved in that. Students, with their youthful idealism, start these conversations, but everyone participates.”

Overseas service and study

As seen in other exhibition cases, Stanford students were especially involved in the war efforts and study abroad.

Jenny Johnson, also an archivist, researched and curated the decades coinciding with the World Wars (1910-20 and 1940-50). Both men and women volunteered in the ambulance corps units in Europe. On display are a male student’s ambulance driver application and a female student’s Women’s Unit emblem.

“There’s a recurring theme of service that shows up again and again in the exhibit,” Johnson said. “Stanford students and the broader Stanford community have proven to be incredibly adaptive and responsive to solving problems, while at the same time always looking forward to improve the world around them.”

Johnson also curated a case covering the Bing Overseas Studies Program. Although study abroad programs at Stanford date to 1957, in more recent years the generosity of Peter and Helen Bing has made overseas studies affordable for many students.

Digital stories

Stanford Stories includes some non-traditional sources such as digital archives. “It’s not just about the diversity of voices,” Hartwig said, “but the diversity of the materials. By including digital materials, we are trying to reflect not just the voices and the students, but also the technology used to transmit the stories.”

Archivists Josh Schneider and Jenny Johnson view the virtual reality film produced by graduate students enrolled in the documentary filmmaking program. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Curators have also prepared an online companion exhibition, which, in Schneider’s words, might “appeal to people who don’t necessarily get their information through the way that traditional libraries and universities have spread their messages.”

Exhibition curators also collaborated with Stanford graduate students Lauren Knapp, Dane Christensen and Aria Swarr in documentary filmmaking. Together, they produced a 4-minute virtual reality film that offers yet another way to tell Stanford stories.

Three satellite exhibitions are also on display: Stanford Athletic Firsts is located in the east wing of Green Library, Stanford Innovators in the Bender Room in Green Library and Incomparable: The Stanford Band is at the Arrillaga Alumni Center.

A call to collect

Stanford Stories also speaks to the challenge of capturing and collecting stories in the digital age. “It’s a very difficult job for us to capture and share contemporary students’ stories,” Hartwig observed.

“This project is a call to arms to collect from current students and alumni,” said Schneider, noting that “we’re trying to make sure that the stories we are collecting are the diverse and inclusive stories that make up a very idiosyncratic campus.”

For Hartwig, “The most important part is for people to realize that there is a university archive, and we care about preserving Stanford stories.” Hartwig and his colleagues welcome students and young alumni to send in their own stories and archives for preservation – including emails, text messages, tweets and selfies.