More than 1 billion people around the world suffer from chronic pain, which can interfere with quality of life, affect a person’s ability to work, and cause or exacerbate mental health issues. Currently, the only consistently effective treatments for chronic pain are opioids, which come with severe risks of addiction and fatal overdose.

Researchers at Stanford University and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have designed a new compound to potentially treat chronic pain that targets type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptors, which are proteins on the surface of cells throughout the body that bind to cannabinoids – chemical compounds made by the body or found in plants like cannabis. In a paper published March 5 in Nature, the researchers demonstrate that the compound can effectively treat multiple types of pain in mouse models without causing the psychoactive side effects typically associated with the CB1 receptor or causing the mice to build up a tolerance to it.

“We rationally designed compounds with the properties that we wanted,” said Alexander Powers, co-first author on the paper, who conducted the work while earning his PhD in chemistry at Stanford. “This molecule shows that we can get a separation between the side effects and the analgesic effects – we can target the CB1 receptor and get the good effects without the bad.”

A cryptic pocket

Researchers have been interested in targeting the CB1 receptor – so named because it is a binding site for the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) molecules in cannabis – to treat chronic pain for decades. Synthetic molecules targeting the CB1 receptor have shown strong pain-relieving properties, but they also tend to cause severe psychoactive side effects and lose their effectiveness over time.

The Stanford researchers started looking for new ways to target the CB1 receptor by running 3D computer simulations of its movements. Like most proteins, CB1 constantly shifts between different shapes, and these structural changes influence which compounds can bind to it and what signals it transmits.

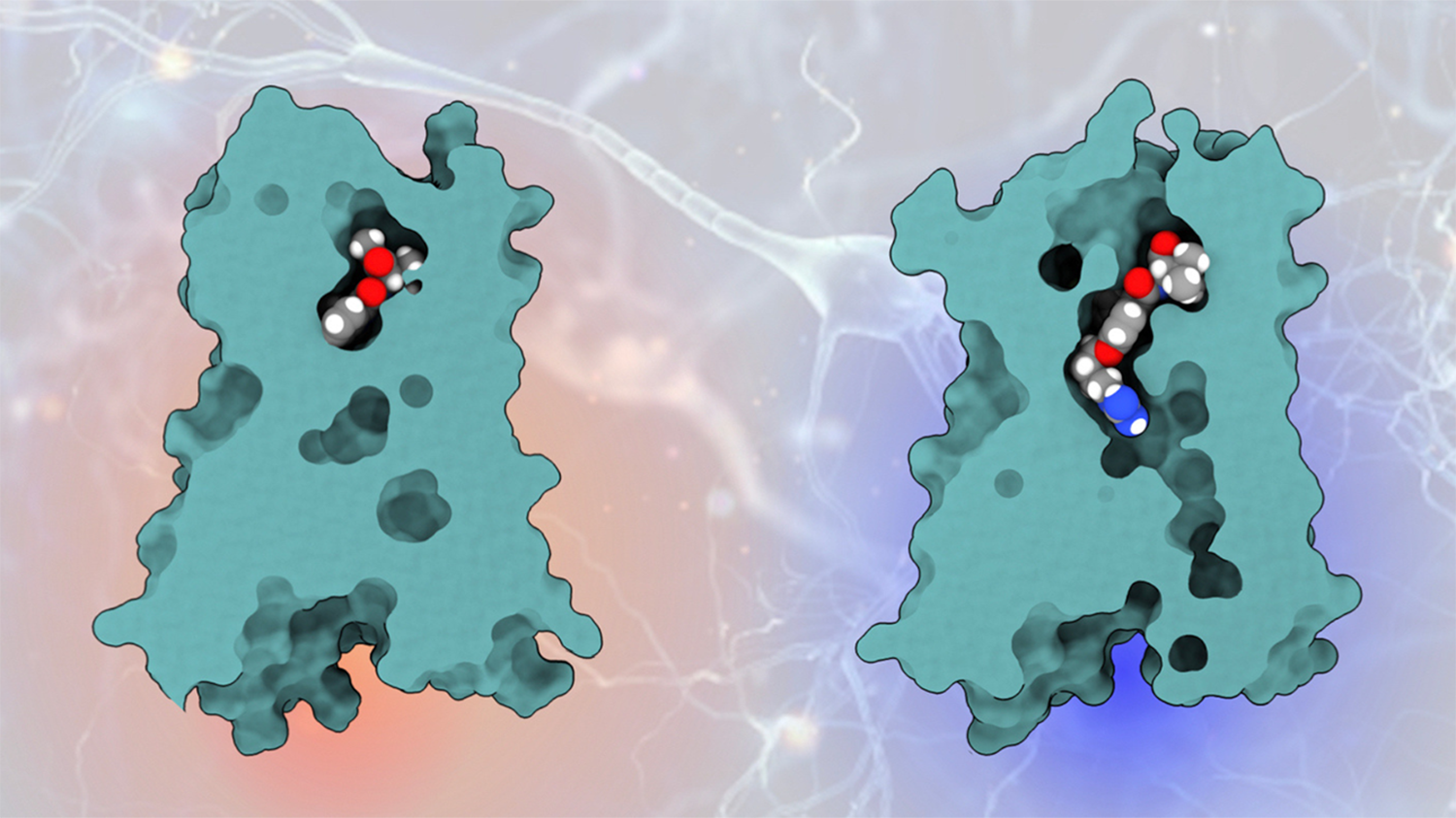

Other groups have identified several structures of the CB1 receptor using experimental methods, but Powers and his colleagues were looking for something new. Through their simulations, they discovered a previously unknown “cryptic pocket” – a binding site that is not present in the experimentally determined structures but opens transiently in simulations.

Molecules binding to CB1 receptor protein: previous molecule (left) and newly engineered molecule engaging the cryptic pocket (right). | Alexander Powers

This particular cryptic pocket had the properties they were looking for. It would allow for a compound with a positive charge, making it harder for the compound to penetrate the central nervous system and trigger psychoactive side effects. And it provided an opportunity to trigger only the biochemical pathway in which they were interested.

“Other cannabinoids that bind to the CB1 receptor cause it to trigger two biochemical signaling pathways,” said Ron Dror, the Cheriton Family Professor and professor of computer science in the School of Engineering at Stanford, and a corresponding author on the paper. One pathway provides the analgesic effect, but the second causes the patient to start building up a tolerance to the drug – the longer a patient uses it, the less pain relief it provides. “We had to find a compound that would trigger one pathway without the other.”

Dror, Powers, and Deniz Aydin, a former postdoctoral researcher at Stanford, computationally designed a set of compounds that fit in the cryptic pocket in their simulations. Then, researchers at WashU Medicine synthesized the molecules and conducted experimental testing. The design that ranked highest computationally also proved to be the most effective in experimental tests.

In mouse models, the molecule proved to be effective at treating inflammatory, neuropathic, and migraine pain. Unlike previously discovered molecules targeting cannabinoid receptors, it continued to be effective throughout the treatment and triggered no psychoactive effects at the dose necessary for pain relief.

A new approach for new drugs

Often, drug discovery involves testing thousands of different molecules to find one that works. Using computational design, the researchers only needed to make and test a few molecules.

“The computational approach was efficient, but what I find most exciting is that it enabled the design of a compound with very different properties than compounds discovered using traditional approaches,” Dror said.

There is still a long process before this molecule, or one like it, could become a new drug to treat chronic pain, but the work highlights a new way to bind to the CB1 receptor and provides a pathway to potentially finding safer, more selective drugs.

“In theory, there are so many cryptic pockets out there to find that could limit side effects at an already drugged target or help design a drug for a target that doesn’t have one yet,” Powers said. “I think it’s a really exciting approach.”

For more information

Additional Stanford co-authors of this research include Brian K. Kobilka, the Hélène Irwin Fagan Chair of Cardiology and a professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford Medicine; Kaavya Krishna Kumar, an instructor in molecular and cellular physiology and staff member of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute; former postdoctoral researcher Evan S. O’Brien; visiting scholar Yuki Shiimura; and graduate students Briana L. Sobecks and Teja Nikhil Peddada. Dror is also a professor, by courtesy, of molecular and cellular physiology and of structural biology; a member of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Stanford Bio-X, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering; a faculty fellow of Stanford Sarafan ChEM-H; and a faculty affiliate of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Other co-authors on this work are from Washington University in St. Louis, UF Scripps Biomedical Research, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the PhRMA Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Media contact

Jill Wu, School of Engineering: jillwu@stanford.edu