To the casual observer, Lagunita might look like an empty field, but Stanford students and conservation experts are reminding the campus community that the area is a natural habitat that needs protection.

“There are really high levels of native biodiversity that inhabit Lagunita, including some very sensitive species of conservation concern,” said Stanford conservation program manager Esther Adelsheim.

To raise awareness, Stanford students and conservationists have teamed up to create and install new artful interpretive signage about Lagunita’s uses and biodiversity.

“We’re hoping the signs will help educate the public about how Lagunita works and the organisms that are found there, as well as how people have historically interacted with the area,” Adelsheim said.

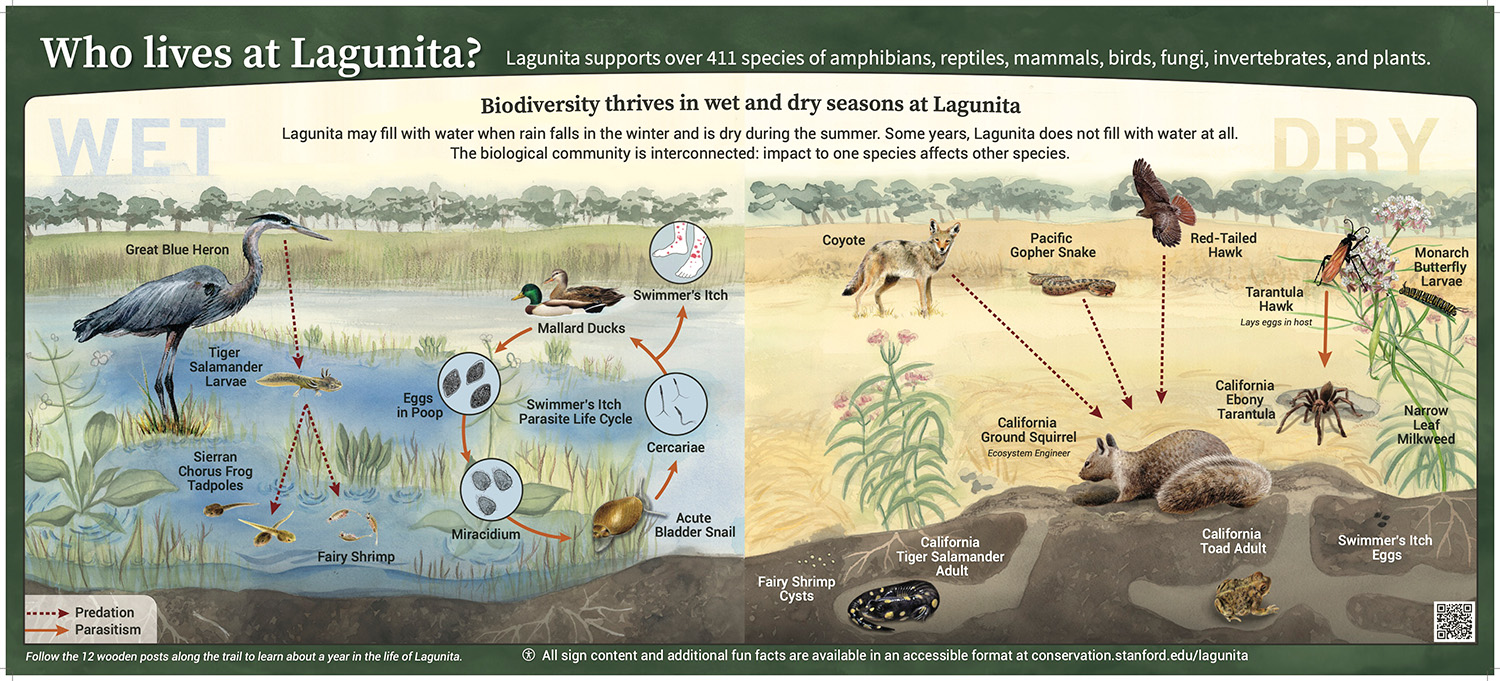

Over 400 native species are found in and around Lagunita, including ducks, snails, fairy shrimp, milkweed, coyotes, squirrels, tarantulas, and hawks. Many species, including an intergrade gartersnake, monarch butterflies, and California tiger salamanders, are at risk of extinction. The salamanders use the area for seasonal breeding, to lay and hatch eggs, and as a refuge from predators.

More than 400 species, including the California tiger salamander, inhabit Lagunita. | Courtesy, Stanford Conservation Program

The signs also aim to dispel misconceptions about the area. “A major misconception about Lagunita is that it’s a perennial and natural body of water that’s full all the time, which is not true,” Adelsheim said.

New signage explains that rising temperatures and persistent drought have reduced the flow of water to the basin, leaving it dry and empty most of the year.

Lagunita was created in the late 1800s as a reservoir to provide irrigation for the orchards and alfalfa fields of the Palo Alto Stock Farm. Today, it serves as a flood control facility and wildlife habitat. It is also the site of ongoing scientific research and teaching.

Students in BIO 159: Herpetology (co-taught by biology professor Lauren O’Connell and Adelsheim) came up with the idea for the signs. With support from an interdisciplinary team of Stanford staff and help from a professional designer, they developed the concept, designed the layouts, and held a competition for student artwork to be included on many signs. The Office of Accessible Education provided input on the signs, which are displayed in English, as well as online in Spanish.

In May, four large signs and 12 smaller posts were installed along Lagunita’s walking path. The smaller posts invite visitors to experience “A Year in the Life of Lagunita” and its seasonal cycles in weather, water depth, and native species. Each sign includes a QR code that directs visitors to further information about the Conservation Program’s work at Lagunita, including updates on the California tiger salamander population.

Adelsheim noted that with summer over, foot traffic around Lagunita is expected to increase significantly.

“As we enter the new school year, we’re hoping that the Stanford community will help steward Lagunita to ensure it remains a safe and clean habitat for the species that call it home and the students and researchers who use the space to learn and teach,” Adelsheim said.

The public is encouraged to continue using Lagunita’s walking path. Stanford community members interested in off-trail activities at Lagunita as part of research, classes, events, organized recreation, or any other university-sanctioned activity can submit an Application for Use of University Foothill Lands.