When most people think of fungi, they think of the part you can see: mushroom caps poking through the soil. But Stanford biologist Kabir Peay knows the humble mushroom sprouts from a vast network of tiny fungal strands branching out below ground, intertwined with the roots of trees and plants.

“If you were to walk around a forest, the ground beneath is teeming with life,” said Peay, director of the Earth Systems Program and an associate professor of Earth system science in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. These fungal networks play a leading role in plant and forest health and could be key to sustainably supporting ecosystems and agriculture in the face of climate change.

Kurt Hickman

“Plants – almost all of them, almost all of the time – are involved in this ancient partnership,” said Peay, who is also an associate professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences. Beneficial fungi known as mycorrhizal fungi colonize the roots of plants, which provide energy via photosynthesis. The fungi, in turn, deliver water and nutrients from the soil to their hosts.

Peay’s interest in mycorrhizal fungi traces back to a fungal biology class he took as a PhD student in the early 2000s, when he was studying environmental science, policy, and management at the University of California, Berkeley. At the time, he was researching impacts from introduced diseases, such as the fungus-like pathogen that had only recently been identified as the culprit for a wave of sudden deaths among oak trees throughout Northern California.

We’re seeing how ubiquitous these positive interactions are and recognizing that nature works as much through cooperation as it does through antagonism.”

“The more I learned about fungi, I realized they were of more interest to me than the plants they were interacting with,” he said. “They are incredibly fascinating, bizarre, and diverse creatures, and they drew me in.”

For more than 20 years now, Peay has conducted experiments in the hills of Point Reyes National Seashore in an area burned by the 1995 Mount Vision Fire to understand how microbial communities change in the aftermath of fire.

In time, Peay’s research has transformed his perspective on nature itself – part of a broader shift in the field of ecology, which long emphasized predator-prey relationships and competition as controlling forces in ecosystems. “We’re seeing how ubiquitous these positive interactions are and recognizing that nature works as much through cooperation as it does through antagonism,” he said. “There are important consequences to that understanding for things like agriculture – these beneficial fungi in the soil are helping plants take up nutrients and increase productivity.”

Andrew Brodhead

Microbial ecology

The team of graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, and undergraduates working in the Peay Lab combine field observation, lab experiments, genetic sequencing, and other techniques to study the biogeography of fungi themselves: their diversity in a particular environment, how they change from region to region, and how they impact the health of the plants they partner with. Uncovering these details helps scientists understand ecosystems more holistically and make predictions on how future environmental changes may impact the system.

The Earth Systems Program that Peay has led since March 2023 is dedicated to training students in interdisciplinary systems thinking. This education is meant to lay a foundation for understanding and solving complex sustainability challenges. It’s fitting, then, that Peay wants his own lab to braid three branches of research together: Identify candidate genes that may be important, use genetic tools to probe and manipulate the fungi, and then test them in field systems. All three approaches will be key to applying scientific knowledge from the lab to solve practical problems.

Biology PhD student Karrin Tennant, for example, is working in the field to see if transplanting aspen trees and their microbes can boost their survival in different environments. Lab member Jay Yeam, also a biology PhD student, focuses on understanding how common mycorrhizal fungi adapt to different environmental conditions on a genetic level – with an eye toward identifying genes that fungi need to help plants cope with wetter, drier, or hotter conditions brought about by climate change.

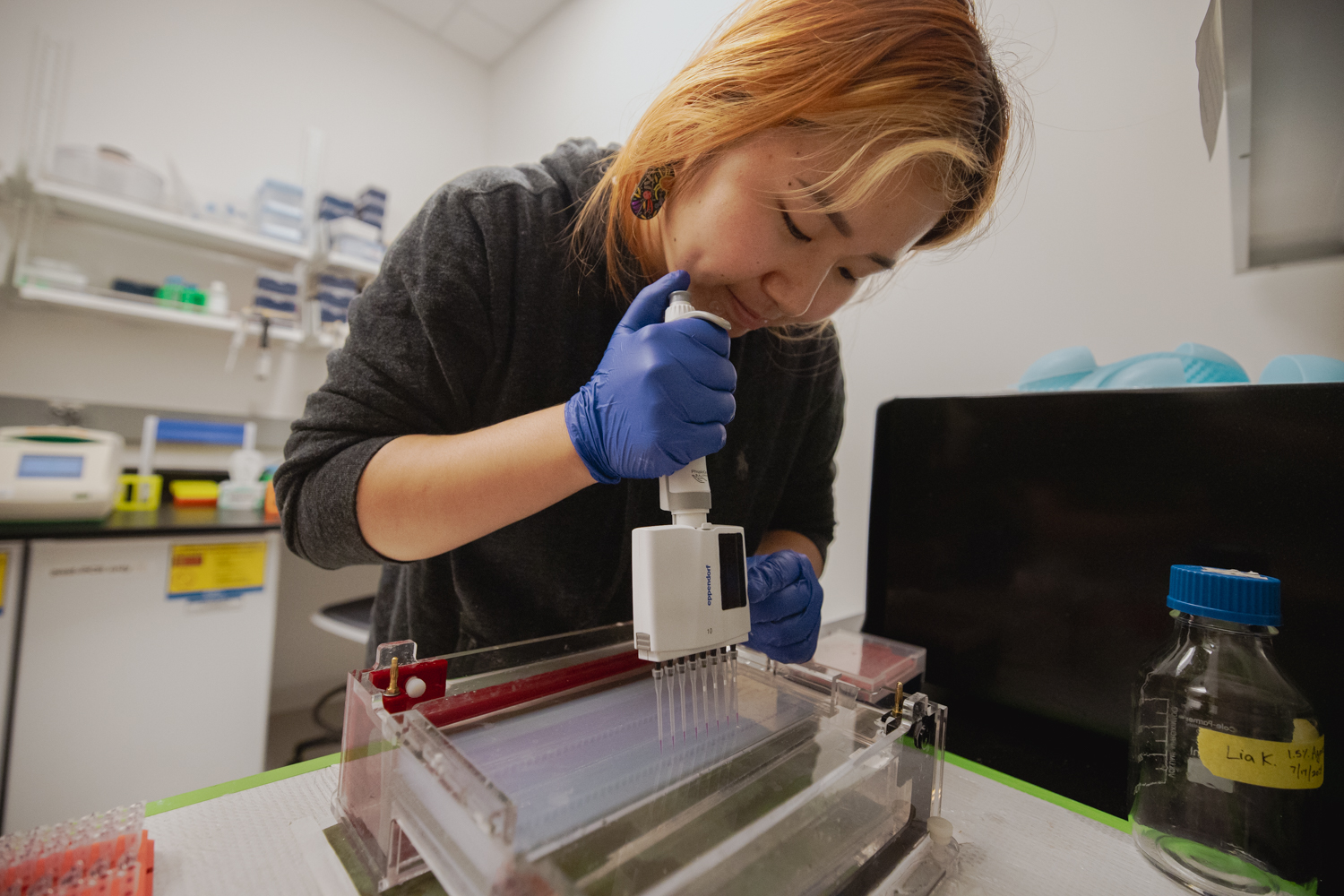

Lia Kim checks the quality of sample DNA in the Peay Lab. | Andrew Brodhead

With funding from Stanford’s Sustainability Accelerator, in collaboration with Earth system science Professor Rob Jackson, Peay is studying relics of old-growth forests to learn which fungal communities enhance carbon storage in soils, whether by taking more carbon from host plants or by trapping it for longer underground. And, to make it possible to test theories about precisely how different genes impact mycorrhizal fungi’s relationships with plants, he is working with bioengineers on a project supported by the Woods Institute for the Environment to develop tools to genetically modify fungi.

Advances in microbiology over the past decade have made much of this work possible. “When I got into the field, there was this global question of what do these fungal communities look like from place to place, and we didn’t have the sampling power to say anything definitive,” Peay said.

“Our big challenge is going from our current foundational knowledge to push through and develop these practical solutions,” Peay said. “Some of our attempts are not going to work – there will be a lot of failure, but that’s how science works. Eventually, that failure can turn into things that will be really useful for us.”

For more information

Kabir Peay is also a senior fellow in the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Media contact

Josie Garthwaite, Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability:

(650) 497-0947, josieg@stanford.edu