In brief

- Mucus from marine snow particles significantly slows their descent, impeding the ocean’s ability to sequester carbon.

- The finding adds a crucial direct measurement to our understanding of how the ocean locks away atmospheric carbon.

- Scientific observation and fundamental research conducted at sea, where processes can be directly observed in their natural environments, are essential for our capacity to mitigate climate change.

New Stanford-led research unveils a hidden factor that could change our understanding of how oceans mitigate climate change. The study, published Oct. 10 in Science, reveals never-before-seen mucus “parachutes” produced by microscopic marine organisms that significantly slow their sinking, putting the brakes on a process crucial for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The surprising discovery implies that previous estimates of the ocean’s carbon sequestration potential may have been overestimated, but also paves the way toward improving climate models and informing policymakers in their efforts to slow climate change.

“We haven’t been looking the right way,” said study senior author Manu Prakash, an associate professor of bioengineering and of oceans in the Stanford School of Engineering and Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “What we found underscores the importance of fundamental scientific observation and the need to study natural processes in their true environments. It’s critical to our ability to mitigate climate change.”

The ocean sequesters 5-10 gigatons of carbon annually. If the plankton can sink low enough in the ocean, that carbon could be stored – away from the atmosphere – for tens of thousands of years.

The biological pump

Marine snow – a mixture of dead phytoplankton, bacteria, fecal pellets, and other organic particles – absorbs about a third of human-made carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and shuttles it down to the ocean floor where it is locked away for millennia. Scientists have known about this phenomenon – known as the biological pump – for some time. However, the exact manner in which these delicate particles fall (the ocean’s average depth is 4 kilometers, or 2.5 miles) has remained a mystery until now.

Marine snow sedimentation with flow field. Artistics rending of real imaging data collected across Gulf of Main using a rotating microscope. | PrakashLab/Stanford

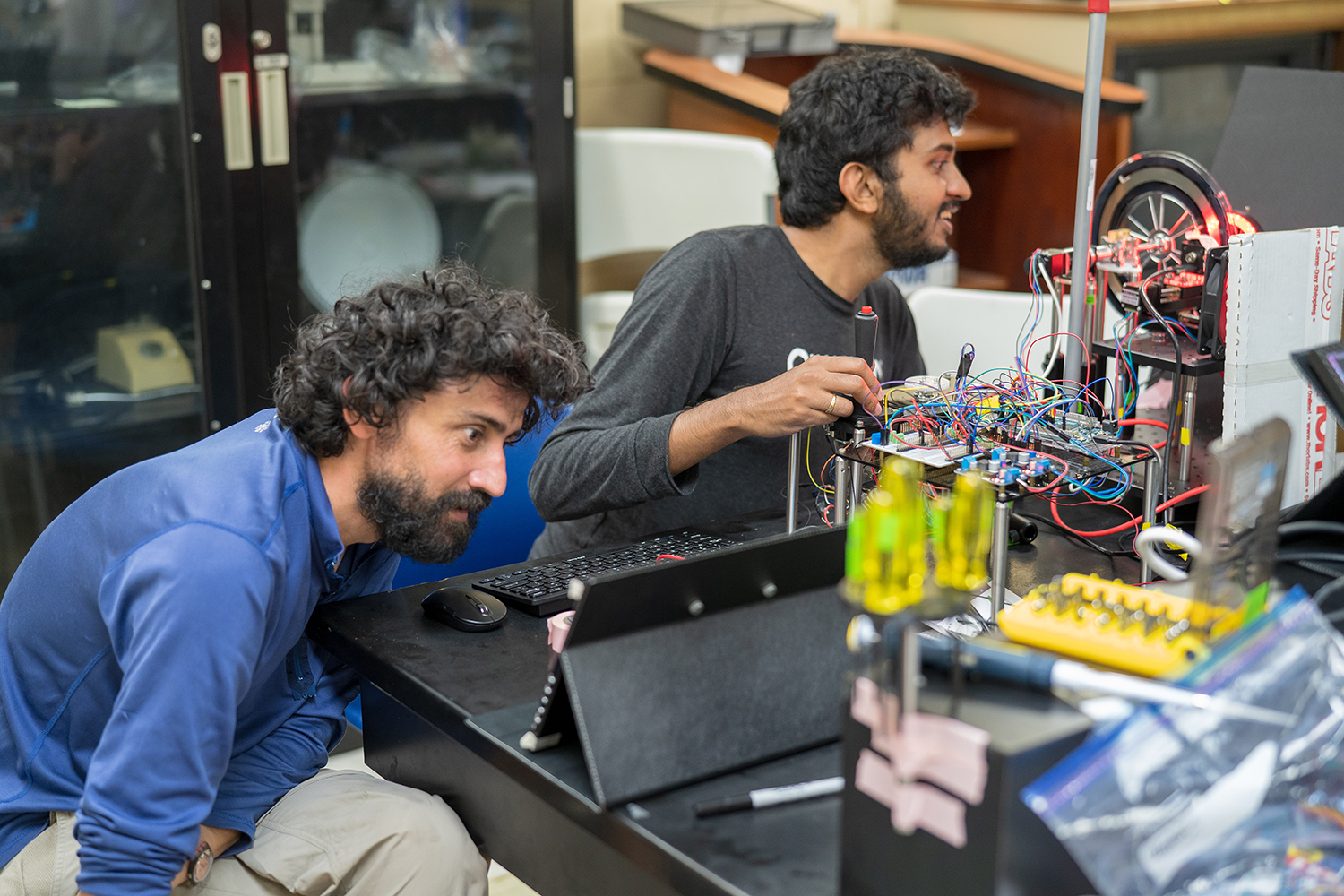

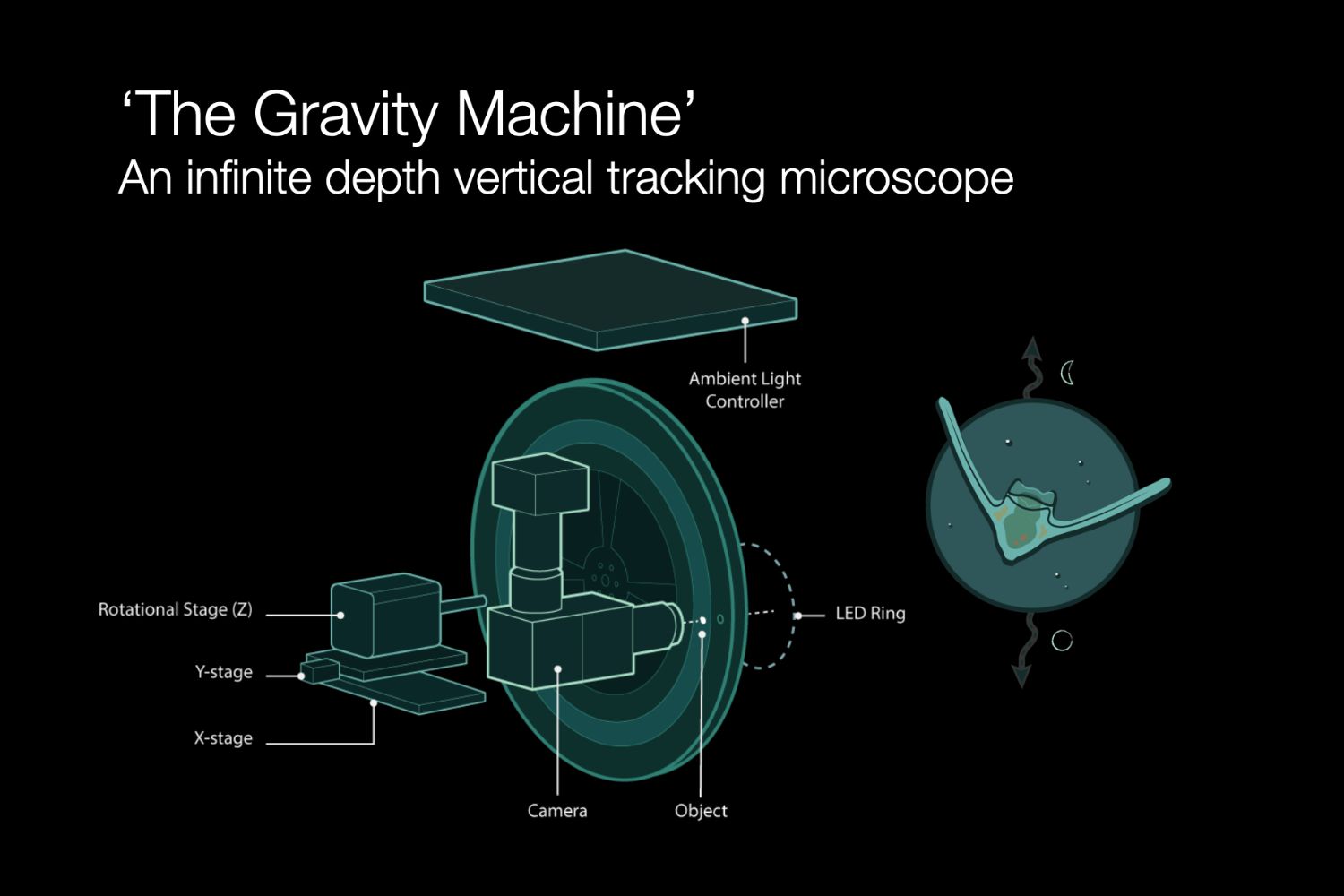

The researchers unlocked the mystery using an unusual invention – a rotating microscope developed in Prakash’s lab that flips the problem on its head. The device moves as organisms move within it, simulating vertical travel over infinite distances and adjusting aspects such as temperature, light, and pressure to emulate specific ocean conditions.

Over the past five years, Prakash and his lab members have brought their custom-built microscopes on research vessels to all the world’s major oceans – from the Arctic to Antarctica. On a recent expedition to the Gulf of Maine, they collected marine snow by hanging traps in the water, then rapidly analyzed the particles’ sinking process in their rotating microscope. Since marine snow is a living ecosystem, it is important to make these measurements at sea. The rotating microscope allowed the team to observe marine snow in its natural environment in exquisite detail – instead of a distant lab – for the first time.

The results stunned the researchers. They revealed that marine snow sometimes creates parachute-like mucus structures that effectively double the time the organisms linger in the upper 100 meters of the ocean. This prolonged suspension increases the likelihood of other microbes breaking down the organic carbon within the marine snow particles and converting it back into readily available organic carbon for other plankton – stalling carbon dioxide absorption from the atmosphere.

Beauty and complexity in the smallest details

The researchers point to their work as an example of observation-driven research, essential to understanding how even the smallest biological and physical processes work within natural systems.

“Theory tells you how a flow around a small particle looks like, but what we saw on the boat was dramatically different,” said study lead author Rahul Chajwa, a postdoctoral scholar in the Prakash Lab. “We are at the beginning of understanding these complex dynamics.”

This work lays out an important fact. For the last 200 years, scientists have studied life, including plankton, in a two-dimensional plane, trapped in small cover slips under a microscope. On the other hand, doing microscopy at high resolution is very hard on the high seas. Chajwa and Prakash emphasize the importance of leaving the lab and conducting scientific measurements as close as possible to the environment in which they occur.

Schematic of gravity machine - a rotating microscope that enables virtual reality arena for plankton and marine snow. The tool enables an infinite field of view microscope in the Z-axis, enabling observation of a sedimenting particle over long periods of time. | Rebecca Konte, PrakashLab/Stanford

Supporting research that prioritizes observation in natural environments should be a priority for public and private organizations that fund science, the researchers argue.

“We cannot even ask the fundamental question of what life does without emulating the environment that it evolved with,” Prakash said. “In biology, stripping it away from its environment has stripped away any of our capacity to ask the right questions.”

Beyond its importance in directly measuring marine carbon sequestration, the study also reveals the beauty in everyday phenomena. Much like sugar dissolving in coffee, marine snow’s descent into the depth of the ocean is a complex process influenced by factors we don’t always see or appreciate.

“We take for granted certain phenomena, but the simplest set of ideas can have profound effects,” Prakash said. “Observing these details – like the mucus tails of marine snow – opens new doors to understanding the fundamental principles of our world.”

Video of marine snow sinking in an infinite water column generated by gravity machine. The sinking marine snow interacts with a wide variety of plankton as it travels through the vertical column. | PrakashLab/Stanford

The researchers are working to refine their models, integrate the datasets into Earth-scale models, and release an open dataset from the six global expeditions they have conducted so far. This will be the world’s largest dataset of direct marine snow sedimentation measurements. They also aim to explore factors that influence mucus production, such as environmental stressors or the presence of certain species of bacteria.

Although the researchers’ discovery is a significant jolt to how scientists have thought about tipping points in ocean-based sequestration, Prakash and his colleagues remain hopeful. On a recent expedition off the coast of Northern California, they discovered processes that can potentially speed up carbon sequestration.

“Every time I observe the world of plankton via our tools, I learn something new,” Prakash said.

For more information

Prakash is an associate professor of bioengineering in the Stanford Schools of Engineering and Medicine; associate professor, by courtesy, of biology in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences; associate professor, by courtesy, of oceans in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability; senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment; and member of Bio-X, the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

Co-authors of the study also include Eliott Flaum, a PhD student in biophysics in the Stanford School of Medicine at the time of the research, and researchers from Rutgers University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

This project was funded by the Big Ideas for Oceans program of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability’s Oceans Department and the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the Schmidt Foundation Innovation Fellows Program, the National Science Foundation, the Human Frontier Science Program, and Dalio Philanthropies.

Media contacts

Manu Prakash, Stanford School of Engineering, Stanford School of Medicine, and Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability: 617-820-4811, manup@stanford.edu

Rob Jordan, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment: 415-760-8058, rjordan@stanford.edu

Note to reporters: More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found athttps://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak/.