As wildfires raged across the Western U.S. this summer, members of Scott Fendorf’s research group drove ahead of the flames in Oregon and Idaho with portable pumps to sample particles in the air for analysis.

For Fendorf and his team, the rising frequency of wildfires represents both a danger and an opportunity. “We now take advantage of the large number of wildfires that are occurring,” said Fendorf, the Terry Huffington Professor in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “When a wildfire comes up, we deploy to the closest place that we can get to, then work backwards from where smoke is coming up and collect particles in the air.”

Fendorf’s team has discovered that wildfires alter metals within soils that impact air pollution, water quality, and potentially plant growth. Their research seeks to inform fire management strategies and help people understand exposure risks during and post-fire.

While Fendorf’s team focuses on the chemical impacts of wildfires, other groups at Stanford are employing robots, AI, and even goats to confront the wildfire crisis. The university conducts innovative research on its diverse lands and in the field, collaborates with area fire agencies, and taps into the ingenuity of its talented students to contribute to wildfire resilience.

“As a private landowner, Stanford is engaging with our regional partners to try out new technology and to use Stanford for what I think the vision’s always been, which is to be a living lab for research and use that work to help other members of the community,” said Cody Hill, associate director of the university’s Resilience and Emergency Response Program.

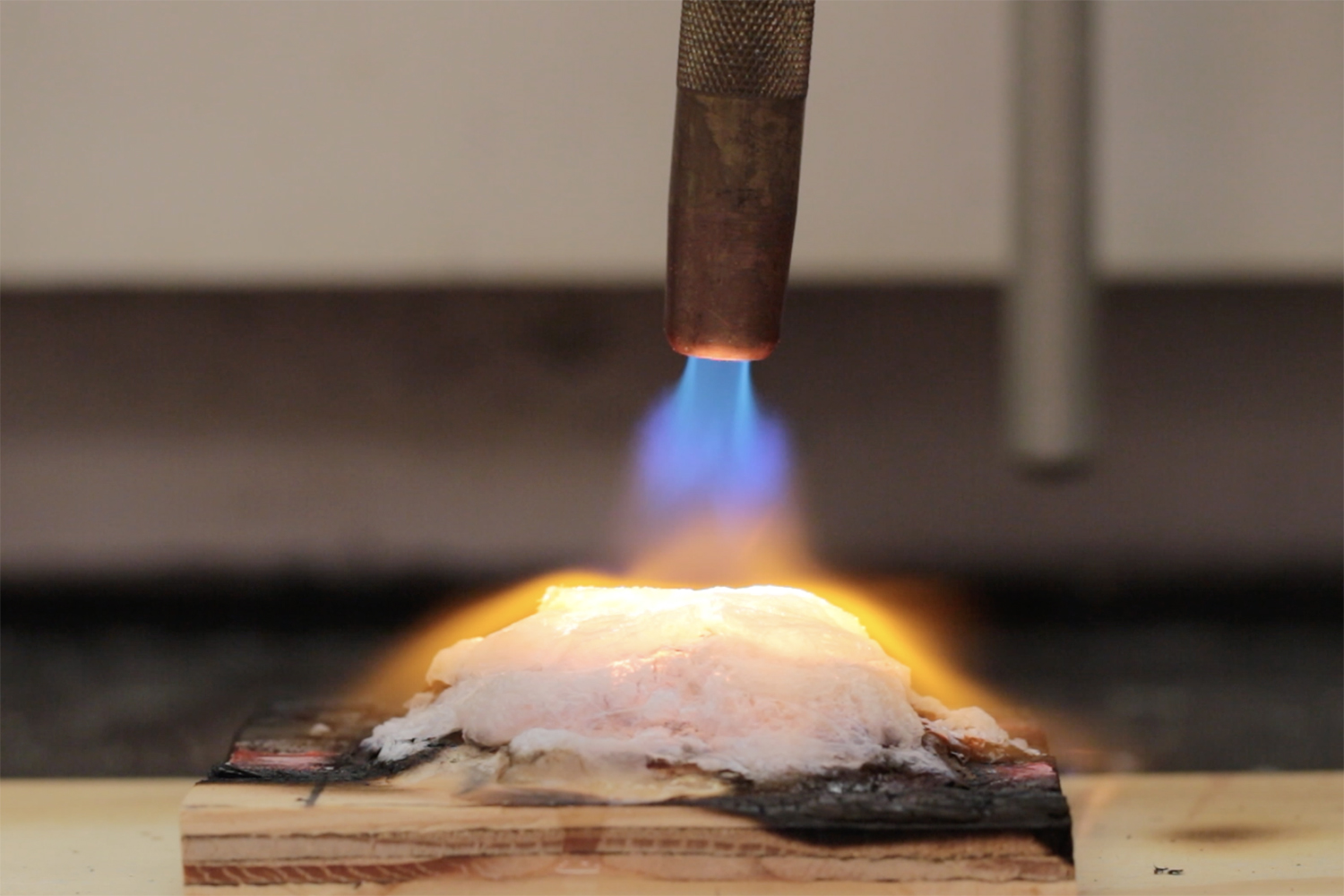

Flames from a prescribed burn at the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve ('Ootchamin 'Ooyakma) in March 2024. | Harry Gregory

Hill is part of the Wildfire Resilience Program at Stanford, a multi-department effort focused on land stewardship activities, fire fuel reduction treatments, and cooperation with local agencies to enhance regional wildfire resilience. The program prioritizes protection of sensitive native ecosystems and cultural resources, support for field research opportunities, piloting innovative technologies, and community outreach.

“Many other universities don’t have the land portfolio that we do, so Stanford is harnessing this opportunity to be good stewards of the land, to be good neighbors, and to test out new technologies,” Hill said.

Caring for the land

Stanford owns nearly 8,200 acres, which includes sizable wildland bordering urban areas and spanning six governmental jurisdictions. As California wildfires have worsened, the university has ramped up its wildfire management efforts, starting with the 2019 Wildfire Management Plan, which has since been updated and expanded.

Completed projects under the plan include working with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area to conduct prescribed burns at the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve ('Ootchamin 'Ooyakma), using machinery or goats and sheep to reduce fire fuel, and removing eucalyptus trees along Arastradero Road. Each project ensures land stewardship activities are conducted in a way that’s consistent with the university’s policies for protecting sensitive species, native ecosystems, and cultural resources.

Stanford is also exploring how technology can be used in early detection of smoke and fire, educating more people about good fire versus bad fire, and increasingly collaborating with regional partners and first responders, Hill said.

The university recently installed more than two dozen AI-based environmental sensors across its lands to provide early wildfire detection. Stanford also has two AI cameras as part of the AlertCalifornia system, which provides live imagery to help emergency responders and the public identify and assess active wildfires.

Esther Cole Adelsheim is an ecologist and the conservation program manager at Stanford who advises the university on land stewardship activities and, together with the Stanford Conservation Program team, implements conservation and restoration projects on Stanford property.

California, like most of the American West, has a history of fire suppression, which resulted in the accumulation of fire fuels and increased likelihood of high severity fire, Cole Adelsheim said. With climate change, the conditions under which fires start and spread have also increased.

“Stanford’s fire management work aims to rectify the impacts of fire suppression and prepare for the growing risks posed by climate change,” Cole Adelsheim said. “We’re adopting well-vetted practices to protect our native biodiversity, our campus, and the safety of our community.”

This includes exploratory techniques, rigorous monitoring of interventions, partnering with academic colleagues, and a careful balance of different goals, she said.

Earlier this year, a local startup piloted its BurnBot machine at the Stanford Dish to create fire fuel breaks in one of Stanford’s grasslands. The BurnBot torches the vegetation at the front of the machine and extinguishes it with water sprayers and giant rollers at the back. The BurnBot contains most of its emissions so there is little smoke, making it an approachable tool for introducing “good fire” into the landscape, Cole Adelsheim explained. Researchers are also looking at how well it supports native plants, which can be harmed by more traditional methods to create fire breaks, like mowing or discing.

The BurnBot creates fire fuel breaks by torching the vegetation at the front of the machine and extinguishing it with water sprayers and giant rollers at the back. | Andrew Brodhead

“What's really wonderful about fire management at Stanford is that there's a great deal of expertise from a multi-disciplinary array of folks that's being applied to this topic,” Cole Adelsheim said.

This wealth of knowledge fuels Stanford’s Wildfire Resilience Program, which brings together researchers from across the university to explore innovative ways to mitigate wildfire impacts. For example, researchers at Stanford have developed a sprayable gel that can help protect homes and critical infrastructure from fire.

“We have people that do really creative work, use a different set of tools, ask really unique and important questions, and take a more global perspective,” Fendorf said.

With wildfires becoming more severe and unpredictable, Fendorf believes our evolving relationship with fire demands urgent new strategies.

“It gives us a directive to start thinking about what we do in the future in terms of management and health risks,” Fendorf said. “And we need to think globally.”

Out-of-the-box thinking

Stanford’s students are also playing a key role in wildfire mitigation through the Big Earth Hackathon, led by senior research engineer Derek Fong. This cross-campus competition challenges students to develop innovative solutions to planetary problems such as wildfires. During the 2024 Hackathon, teams addressed the issues of wildfire prediction and mitigation, as well as issues related to equity and access to information.

“Our planet has some major problems, and we need creative solutions,” Fong said. “Students bring a fresh perspective and often come up with innovations that nobody has thought of. That’s really the spirit behind the hackathon.”

Student teams competing in the Hackathon have come up with ideas that have since become reality, such as a worldwide wildfire risk map and biodegradable water pellets that improve aerial firefighting.

“The Hackathon gives us the opportunity to explore innovations using one of our greatest gifts: our students. They have intellectual curiosity and creativity that is rarely matched anywhere,” Fong said. “We’ve got all this brain power at Stanford and if you can focus their attention on planetary problems, the sky’s the limit.”

For more information

Fendorf is a professor of Earth system science and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment.