Astronauts sit cross-legged in a circle, reflecting meditatively. A rocket descends toward a planet, its brilliant glow illuminating a city made of mushrooms. These far-out images graced the final presentation boards of the students who’d completed the Introductory Seminar (IntroSem) titled How to Shoot for the Moon, exemplifying out-of-the-box solutions for problems in space travel, such as staying connected with humanity and sustainable space homes.

In this IntroSem, first- and second-year students were taught design mindsets to help them envision space-related, human-centered technology. Throughout the course, they formed connections with industry professionals, who attended their final design presentations and gave students exposure to pitching and actual careers in aerospace design and engineering.

More than that, though, the teaching team prompted the students with weekly design challenges that pushed them to think about some of the universe’s biggest questions – Who are you? Why are you here? What do you want? And how will you get it? – and how to apply those to their academic, career, and personal journeys. In other words, the teaching team wanted to ensure that students would come away with skills that would help in their overall mission, not just their major.

“I think it’s important to point out that we, the teaching team, don’t even have these answers for our own lives, because those answers are always evolving,” said Seamus Yu Harte, a lecturer in the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (known as the d.school) and one of three instructors for the course. “The curriculum of this class is at the cutting edge and that dramatically closes the gap between teacher and learner. We’re collaborating across different disciplines, connecting students with industry professionals, and just bringing ideas that are new, even for us as teachers, to explore.”

Where humanity and space meet

Now in its second year, the course is a unique collaboration between the d.school and the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, both in the School of Engineering. The course was designed by three instructors: Harte and Miki Sode, both d.school lecturers, and Debbie Senesky, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics.

The course emphasizes collaboration and brainstorming rather than traditional homework assignments. Each class was centered around a different element of space travel, such as food production, mental health, living spaces, and social rituals. This year, the course also included a mushroom theme, which prompted discussions around sustainability and the many uses of mushrooms: as building material, medicines, nourishment, and more.

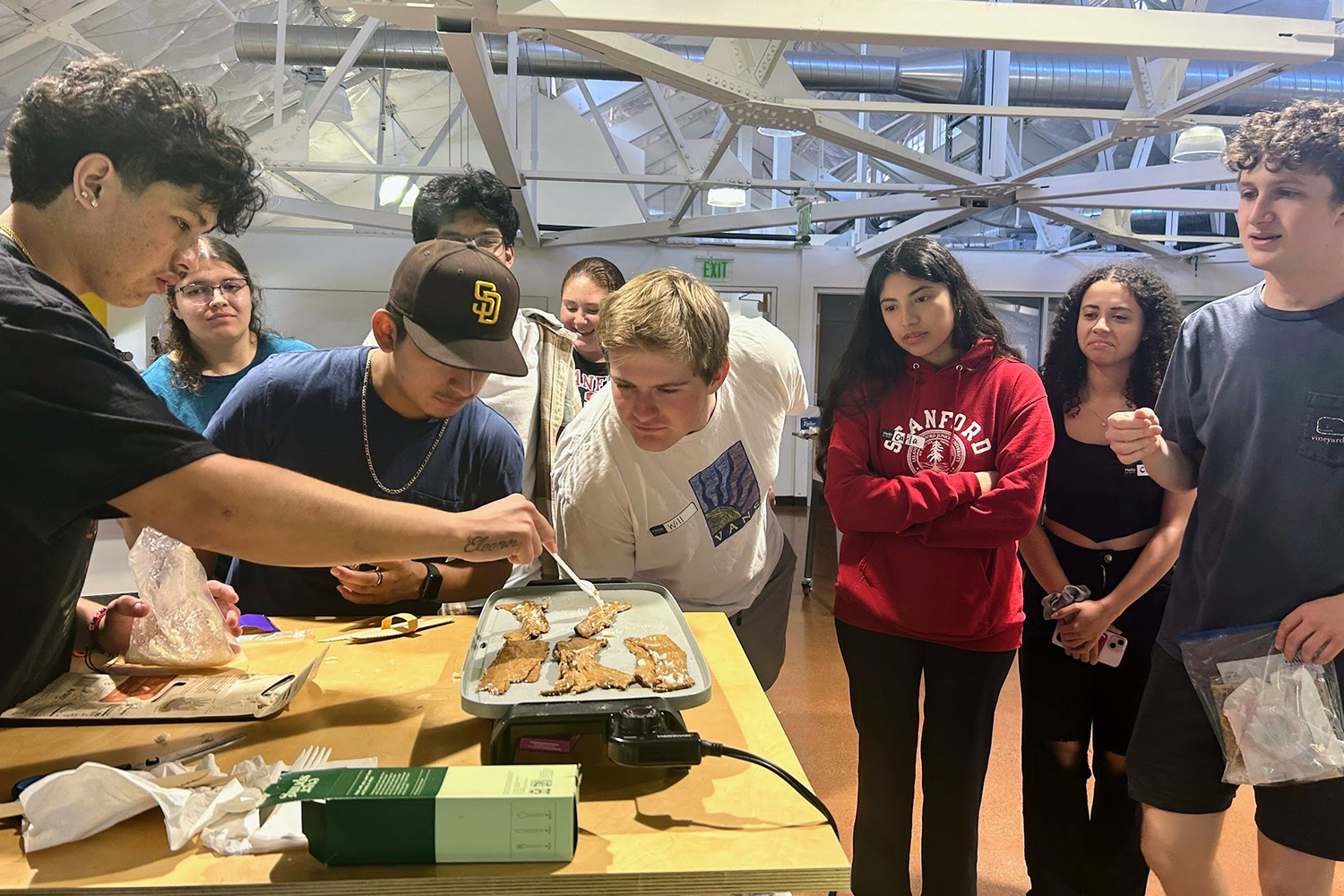

The class prepares to taste mycelium (mushroom) bacon. | Miki Sode

Senesky highlighted that the teaching team wanted students to “exercise different muscles” by learning about aerospace and design through projects that promoted self-expression and earnest engagement. “Radical collaboration is a d.school principle that encourages and enables multidisciplinary, intergenerational, and multi-institutional teams. That kind of collaboration between the students and teachers is a theme of the class and something I’m interested in as an educator,” she said. “I think it really enhances teaching and the curriculum.”

A note from the d. school on radical collaboration

“To inspire creative thinking, we bring together students, faculty, and practitioners from all disciplines, perspectives, and backgrounds – when we say radical, we mean it! Different points of view are key in pushing students to advance their own design practice. Our methods become a shared language for groups to navigate the ups and downs of messy challenges.”

Sode, who left her position at the International Space Station National Laboratory to work in human-centered design thinking, agreed. “There’s something in the intersection of humanity and space that we all can connect on. This year, I think we cultivated a sense of psychological safety that allowed students to be vulnerable and engage more with each other.”

Imaginative, science-fiction-like design challenges coaxed students to explore both their inner and outer universe and apply those interrogations as an integral part of developing solutions. For example, in a class titled “Tang Sucks,” the students had to reflect on nutrition in space; they had to consider what food can realistically be brought on a flight or grown in zero gravity, as well as what kind of foods are enjoyable or even culturally significant to people. Other days, students journaled with guest speakers, like biologist, naturalist, and educator Melinda Nakagawa who prompted the students to think about how organisms make their home out in the wild, and how people might do that in new, uncharted landscapes.

Students making mission patches, like those that NASA and other space agencies create for missions. They were asked to make six patches using a different medium for 90 seconds at a time. | Miki Sode

First-year students Jackie Pena and Kenna De La Rosa said their class became close through working on design challenges together and their instructors’ encouragement to be introspective about what mattered to them. The two recounted that they were “never really sure what was going to happen” when they attended class each time, but that they wished they could do the course again.

Rocketing toward the future

In addition to their design challenges, students heard from many voices across the industry. Their classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays included lectures from leaders at Blue Origin, SETI Institute, Google X, and more. Some students even met with their personal heroes through those presentations.

First-year student Will Neal-Boyd got to meet astronaut Christopher Sembroski, who he wrote about in his application to Stanford. “I’ve never had a class like this,” said Neal-Boyd. “It’s not what you would expect at all, but it feels like a stepping stone to my future.” Neal-Boyd is interested in space architecture – the building of structures that would be inhabited in outer space – and the combined d.school and engineering principles gave him an opportunity to explore that passion. “Getting to talk to guest speakers about space architecture showed me that this is possible,” he said.

In one of their final classes, students pitched their goals for the future to industry professionals in aerospace, design, and engineering. The projects spanned a wide variety, including establishing modular nuclear energy plants for clean energy and using bioengineering to produce sustainable materials for space travel.

While the final projects were space (and mushroom) themed, the tactics and ideas the students took away from the course go beyond those bounds. For example, Saul Hernandez, a first-year student with “no experience” in aeronautics or astronautics, hopes to someday apply what he learned about human-centered technology and problem solving to green energy development in El Salvador, where he and his family dealt with energy instability.

Harte, Sode, and Senesky are enthusiastic about the future of the course and continuing to stoke their students’ curiosity in big questions. Harte believes that this year cemented their proof of concept and he’s excited about bringing the experimental nature of the course to more people, perhaps even students outside of Stanford.

“Miki, Debbie, and I are one of the best and most diverse teaching teams I’ve been a part of,” he said. “Because of that, and the radical collaboration of this teaching team, we are able to take bolder steps than any of us could have alone.”

Harte said that pursuing design challenges like “How might mushrooms help us make a home on the moon?” would have been professionally risky if any of them had pursued it on their own. “But because of the diverse background and expertise of our teaching team and the network we bring to the classroom, suddenly that wild question became not only interesting but almost obvious as to why it’s important we pursue it. That can only happen through radical collaboration.”

“My major takeaway for this course is that anything is possible,” said Senesky. “The work that these students do here, the connections they have with their community at Stanford offer so much. When I see how our students get inspired by each other and how they get the chance to connect with industry professionals because they’ve had support from each other and the chance to experiment, it shows me what can be achieved through this course. So be open, think big, and really, shoot for the moon.”