On March 16, 2020, Dr. Sara Cody, public health officer for Santa Clara County, walked to a podium piled high with microphones and, amid a surging spread of COVID-19 cases, steadfastly announced a shelter-in-place order for the next three weeks.

News outlets advised that once the order went into place at midnight, life as people knew it would change. Places like bars and gyms would close, but grocery stores and banks would remain open.

Santa Clara County was then the epicenter of the Bay Area’s COVID outbreak, and Cody crafted the order with six of her Bay Area counterparts, consequentially becoming known as the architect of the nation’s first shelter-in-place order.

“It’s so much power to hold, it’s overwhelming,” Cody said. “In that moment, standing before the TV cameras, I realized the buck stops with me, and it was my decision – a decision that’s going to have such a profound impact on everybody in the county.”

Dr. Sara Cody announces a shelter-in-place order during a March 16, 2020, press conference in San Jose. At the time, there was a nationwide shortage of personal protective equipment, no vaccines, and only an emerging understanding of COVID. | Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group

Time to reflect

Three years later, Cody arrived at the scenic hilltop campus of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) at Stanford to complete a year-long fellowship reflecting on her experience in the pandemic, which she is documenting in a memoir.

Since 1954, CASBS has brought together scholars from diverse fields to advance understanding of complex social problems and human behavior. Its renowned residential fellows program hosts around 40 distinguished scholars and practitioners annually.

Thousands of scholarly articles and approximately 2,000 books have been conceived, started, or finished at CASBS - many becoming foundational works with influence on academic discourse, contemporary thought, and public policy for decades.

Cody’s writing space at CASBS included a colorful blizzard of sticky notes forming a timeline around the room. Here - with a bucolic view of a beautiful tree and passing wild deer - Cody explored themes of safety, trust, death, disillusionment, chaos, abandonment, collective action, sacrifice, individualism, connection, and the central paradox of public health: “When we’re good at what we do, what you see is nothing because we’ve prevented that bad thing.”

“There are all these threads and they all wind around this dance with the virus and our many relationships to the virus,” Cody said.

Dr. Cody says the fellowship at CASBS “has been an incredibly rich environment for me to think about my recent work responding to the pandemic and to get input from a whole wealth of social scientists.” | Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences

The beginning

Cody, a Palo Alto native and a self-described “serious local,” earned her undergraduate degree in human biology at Stanford and completed her internal medicine residency at Stanford’s hospital.

Cody developed an interest in the social, economic, and political factors underpinning public health. After residency, she trained with the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) as a sort of disease detective. By the end of her EIS fellowship, Cody was working at the Santa Clara County Health Department.

More than 20 years later, the nation’s first COVID case was reported in Washington in January 2020. Within weeks, Santa Clara County reported its own case, the seventh in the U.S. On Feb. 6, a 57-year-old woman died in her Santa Clara County home, marking the first COVID death in the nation. Cody had a feeling “something very bad was happening” but lacked the data to confirm it.

To address this, the county health department leveraged its relationships with academic advisors from Stanford, UCSF, and Berkeley.

Joshua Salomon, professor of health policy, helped gather faculty, trainees, and other researchers from Stanford and elsewhere to lend expertise in infectious disease modeling and data analytics in hopes of informing the public health response locally and nationwide.

This quickly-assembled unit used county data to build models that were updated in real-time and shared with county epidemiologists to track the impact of the epidemic, underlying transmission trends, and potential effectiveness of public health measures.

“It allowed us to work faster and make better decisions,” Cody said.

The unit also advised county epidemiologists on developing their own models for planning and envisioning different scenarios. “In the early weeks especially, we were learning more about the virus every day,” Salomon explained, “but we hadn’t yet seen the first peak of what would eventually turn into multiple waves, so there was a lot of uncertainty about when that peak might arrive, how high it could be, and what would happen next.”

“Dr. Cody led the nation in making tough, decisive calls that saved a lot of lives,” Salomon continued. “She and her team were deeply committed to bringing evidence to bear on reasoned decision-making in an unprecedented public health emergency.”

Cody’s team also worked with Alexandria Boehm, the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Professor of Environmental Studies, to track the virus through wastewater. This approach provided Santa Clara County with uniquely comprehensive insight into the virus’ prevalence.

Additionally, the Santa Clara Public Health Department collaborated with the Stanford Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab (RegLab) to identify data-informed pandemic interventions. These included measuring the impact of policies on mobility and travel patterns, improving contact tracing, and matching the COVID test supply with vulnerable communities.

“It was central early on to have the best scientific evidence available in trying to craft the county’s response,” said Daniel Ho, director of the RegLab and a CASBS faculty fellow. “We were just learning about this virus, and part of the reason the county was so forward-looking in its response was how well Dr. Cody was able to engage input from the scientific community.”

Drawing on their experience in the pandemic, Cody, Ho, and RegLab’s Executive Director Christine Tsang each testified in the state senate this year in support of talent exchanges to make it easier for state and local government entities to access scientific expertise and to provide researchers deeper insight into on-the-ground realities.

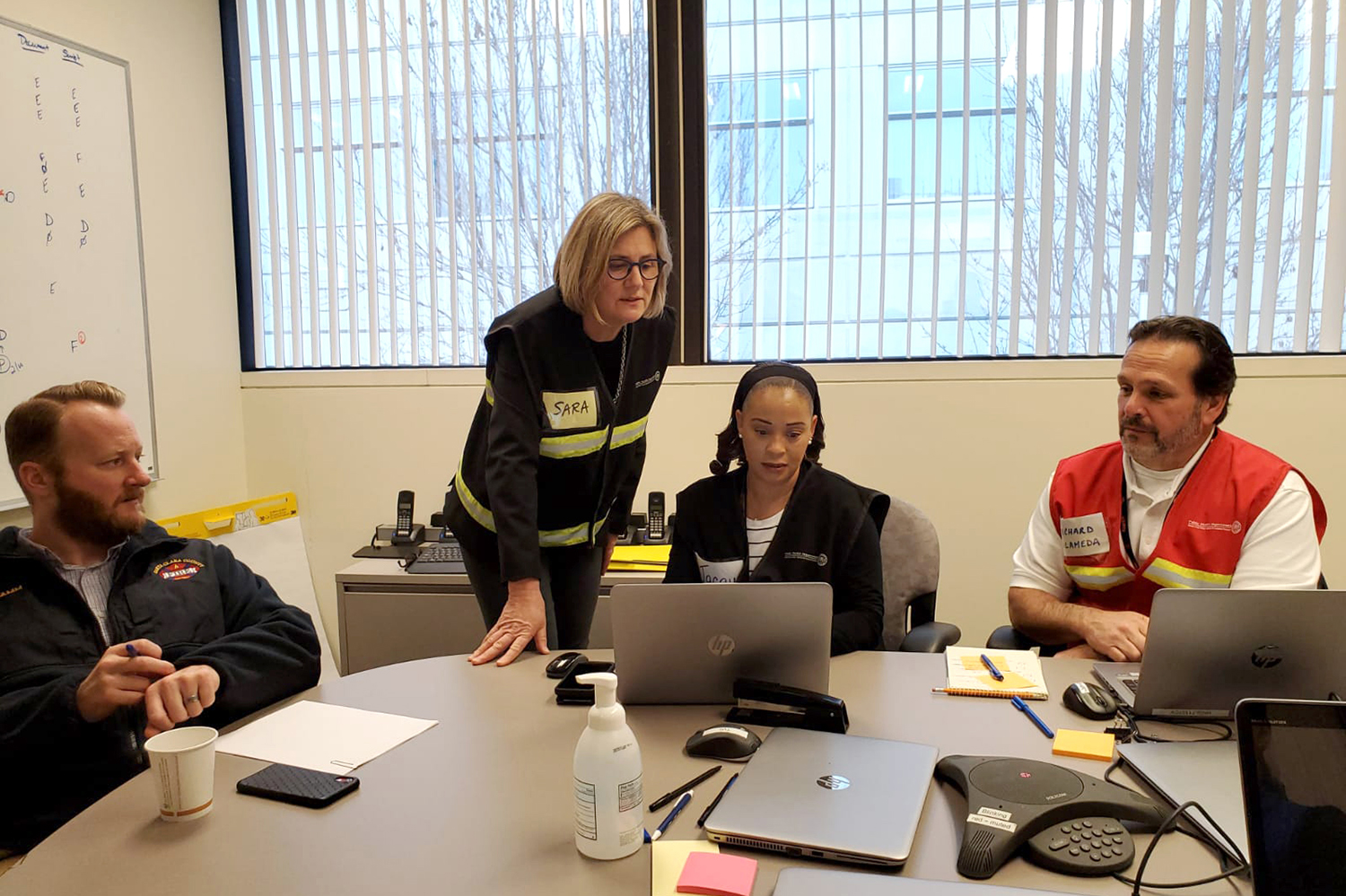

Dr. Sara Cody discusses emergency operations with Santa Clara County staff on March 6, 2020. | Courtesy of the County of Santa Clara Public Health Department

Pandemic intensifies

As Cody and her team were frantically gathering data, the pandemic was worsening. In late February, a Santa Clara County woman who hadn’t traveled outside the U.S. tested positive for COVID – the third case of community transmission in the U.S.

With more testing, the county saw an exponential growth in cases, deaths, and people in ICUs. On March 9, Cody issued an order prohibiting gatherings greater than 1,000 people. Days later, she choked up as she issued another order prohibiting gatherings of more than 100 people and restricting gatherings of more than 35.

“I was just thinking, ‘I can’t believe I’m doing this,” she said. “That means no weddings, no funerals, no celebrations, nothing. This has such a profound effect on people’s ability to live their life, but this is going to prevent more deaths.”

Models indicated that Santa Clara County was about two weeks behind Northern Italy, one of the regions hardest hit by the virus, in case counts at the time. On Sunday, March 15, she called Bay Area counterparts to discuss their data, and they drafted a stay-at-home order as the best course of action.

The following day, Cody and six other Bay Area health officers made the announcement to a stunned room of journalists and county officials.

Three days later, California issued its own shelter-in-place order.

‘A total scramble’

As 2020 continued, differences in state and local orders created discontent, and industries began intensely lobbying to reopen. Cody said she often felt abandoned by state and federal governments and was left to make unpopular decisions alone.

Her own actions made her virally unpopular at times. During the press conference to announce the first case of community transmission in late February, Cody advised people to avoid touching their eyes, nose, or mouth, but as she held a thick stack of papers, she unconsciously licked her finger to turn the pages. One of her children soon informed her that she was the number one meme on TikTok. In a rare moment of levity at the time, her colleague teased her with a drawing of her with a dog cone around her neck.

In April, protesters appeared outside Cody’s home in the afternoons, parading with signs up and down the block. Later, more protesters appeared in the evenings, honking horns, and banging pots and pans for hours while shouting phrases like, “This is not communist China,” “You’re a murderer,” “I don’t know how you live with yourself,” and “You answer to us and you’re going to answer to God.” A pair of sheriff’s deputies were assigned to Cody for her safety shortly after the shelter-in-place press conference, and on many days, more deputies were assigned to protect her family.

When health officials learned that even people who did not exhibit symptoms could transmit COVID, it complicated their ongoing reassessment of risks. “It was very chaotic and a total scramble,” Cody said. “Every time you allow more activity, you might spark a chain of transmission that could lead to someone dying.”

Even as PPE and testing supplies improved, it became “fantastically difficult” to decide how to ease restrictions in different communities that varied in their epidemiology, Cody said. A winter surge in COVID cases began in November 2020, and a vaccine hadn’t arrived yet.

“Hospitalizations and deaths were starting to pick up and I felt responsible, like there was something more that I should do but I couldn’t figure out what that was,” Cody explained. “It was a really difficult time, and people had different ideas about what the right thing to do was.”

The story

By 2023, Cody was mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausted. Seeking to make sense of her experience, she joined CASBS, which not only offered her time, space, and expertise to write, but also a community of social scientists who supported and challenged Cody in her reflections.

“It’s a fantastic environment to do a project like this and feel restored after a really difficult few years,” Cody said. “It’s so beautiful and peaceful here.”

Cody’s memoir explores decision-making under great uncertainty; what enabled her to act quickly; the role of governmental structure; the impacts of her decisions; and the forces at play during a chaotic time in public health and history.

Cody’s book also examines her core assumption that a robust public health system is necessary for communities to flourish. She also explores the tension between usual public health practice – which is deliberative, lengthy, and emphatic on community engagement – and public health practice during an emergency, which is encoded in state laws, happens rapidly, and has little formal structure for collecting public input.

“I wanted to tell the story of what happened because the pandemic, in large part, was fought county by county and there’s over 3,000 counties across the United States,” Cody said. “It was this absurd patchwork, and a local story is an important one to be told.”

For more information

The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford is located within the Office of the Vice President and Dean of Research.

Boehm is a professor of oceans and a senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment.

Ho is the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, a professor of political science and (by courtesy) of computer science, and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic and Policy Research and the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

Salomon is a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and founding director of the Prevention Policy Modeling Lab.