A coming-of-age story about a Palestinian youth growing up in a refugee camp during the 1960s. A childhood account of what life was like in Lebanon at the height of the country’s civil war in the 1980s. A mother’s search for her son who disappeared during Iran’s 2009 election.

These stories – as told in the graphic novels Baddawi (Just World Books, 2015), A Game for Swallows: To Die, To Leave, To Return (Graphic Universe, 2012), and Zahra's Paradise (First Second, 2012) – were some of the books Stanford students read in the spring quarter course, COMPLIT 254: The Middle East Through the Graphic Novel.

Every week, students read one or two graphic novels from a different country in the Middle East to learn about a particular moment in history.

“For any course, it is a huge challenge to talk about the Middle East – it’s a huge region with many people and countries, each with different systems of government, religion, language, and ethnicity,” said Ayça Alemdaroğlu, a research scholar and the associate director of the Program on Turkey at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) who co-taught the class with Burcu Karahan, a lecturer in comparative literature in the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S).

“But graphic novels provide us with a way to think about those histories through stories, narratives, and observations,” Alemdaroğlu said. “Graphic novels get to the point, easily and fast.”

Ayça Alemdaroğlu was one of the course’s co-instructors. | Andrew Brodhead

Worth a thousand words

Alemdaroğlu and Karahan began the first class of the quarter by showing students maps of the Middle East to convey just how diverse and expansive the area is, which covers nearly 3 million square miles and 17 countries.

But they also used maps to explain some of the recent geopolitical shifts that have made the Middle East what it is today.

“We started with maps to describe the making of the modern Middle East after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and World War I as a way to show how borders were drawn and states were formed,” Karahan explained.

The first graphic novel students read was Aivali (Somerset Hall Press, 2014) by the Greek political cartoonist Soloúp. The book describes events following the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, particularly the population exchange between the Greek and Turkish governments that saw some 1.5 million Ottoman Greeks forcibly displaced from their homes – an event which some historians refer to as “The Catastrophe” and the “Asia Minor Disaster.”

The course then progressed chronologically through key historical moments, like the Palestinian uprisings in the early 1990s in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in Joe Sacco’s Palestine (Fantagraphics, 1996), the financial and economic unrest in Egypt in the runup to the Arab Spring protests in Magdy El Shafee in Metro: A Story of Cairo (Metropolitan Books, 2012), and the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis in Don Brown’s graphic novel, The Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees (Clarion Books, 2018).

These graphic novels, complemented by supplementary readings, contextualized themes such as the migrant experience and diaspora, personal and collective memory, colonialism, revolution, and modernization.

Burcu Karahan also co-taught the course. | Andrew Brodhead

Enriching an understanding of a place and its peoples

What makes graphic novels particularly impactful tools for teaching are the ways in which they encapsulate the sensory aspects of a place – for example, the post-war rubble in the background of a landscape or an item of clothing.

Even facial expressions and the spectrum of human emotion – such as fear, anxiousness, confusion – can bring students closer to the characters and the country they live in.

“One of the takeaways for me was how to read images – pictures tell a story,” said Nazli Dakad, ’24.

For example, students were encouraged to look at the artistic and narrative style and describe the artistic choices made, like what color and symbols were used? How were panels and frames arranged? What was the main theme of the book, and in what way was it visually represented?

Creating a graphic novel of their own

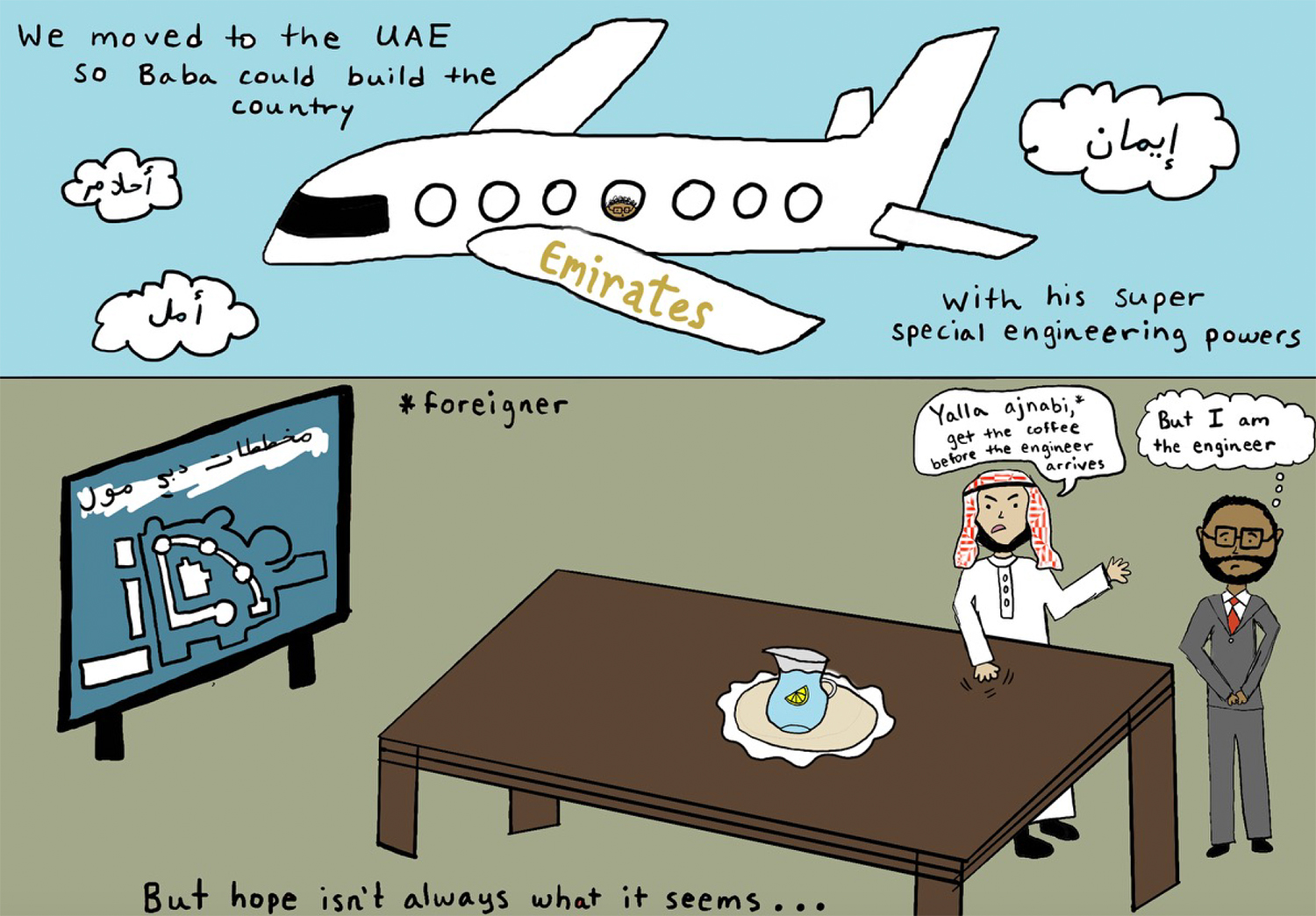

For their final project, students could create their own graphic novel. Nina, an international relations major who requested she be identified only by her first name, depicted her partner Hasan’s childhood experiences in the United Arab Emirates.

Nina’s 34-page graphic novel tells the story of when Hasan, who is of Pakistani American descent, and his family moved to Dubai for his father to pursue a career in engineering.

“This project captures the difficulties of growing up in a place where you are perceived as lesser than, while still holding on to the nostalgic joy and silliness that inevitably comes with childhood,” Nina said. Some of the challenges she portrayed included the stereotypes Hasan’s father experienced as a migrant worker.

“There’s so much richness and varied meanings you can decipher,” Karahan said.

Karahan added: “By bringing all these details together, graphic novels enrich a student’s understanding of a region at a particular moment in history that you cannot find in text-based books.”

They are also details that can’t be conveyed by a number or statistics either, said Jacqueline Beccera, ’24.

For Beccera, seeing a country’s history presented in the format of a graphic novel deepened her appreciation of the place and its people.

“I left with a completely nuanced understanding of the human side of the story – instead of just focusing on numbers and titles, or dates in legal frameworks,” said Beccera, an international relations major.

Nazli Dakad, ’24, took the spring quarter course, COMPLIT 254: “The Middle East Through the Graphic Novel.” | Andrew Brodhead

A tool for empathy

Many of the graphic novels were also stories about coming-of-age and grappling with universal experiences of growing up, from establishing one’s own sense of identity and agency to seeking independence to confronting social norms and family expectations.

“Because a lot of the protagonists were children in the books, the focus wasn’t just on the historical events but what it was like growing up,” said Dakad. “I think that creates a connection between the reader and protagonist that you don’t get when reading a news article. Even though you are learning about history, you are also gaining more empathy because you're reading a story.”

Beccera was also struck by the empathy that graphic novels inspire.

“Storytelling is the kindest, most loving way to bring a differing perspective,” Beccera said.