As Stanford’s Markaz Resource Center marks its 10th anniversary this year, it is broadening its reach to spearhead discussions among higher education professionals at American universities about campus life for Muslim students.

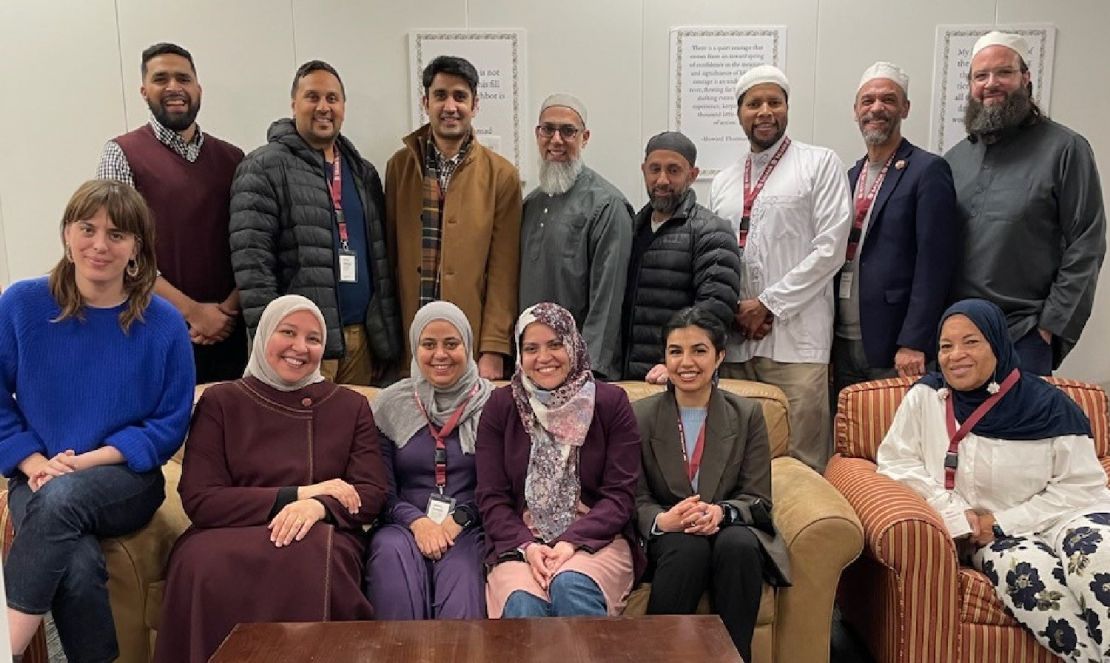

The Markaz hosted its first Muslim Campus Life Summit on January 29 and 30. A dozen participants came from universities all over the United States, representing chaplain’s offices, student affairs and diversity offices, and academic researchers.

“It was unprecedented to bring those constituencies together, and the Markaz Center was uniquely positioned to do this type of convening,” said Amer F. Ahmed, vice provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion at the University of Vermont. “This was an opportunity to connect the spiritual dimensions of Muslim experience with the lived reality that comes with being identifiable as a Muslim person in the United States.”

A diverse community

Services for Muslim college students have traditionally been housed in religious and spiritual life offices, many of which added Muslim chaplains in the years after 9/11, said Abiya Ahmed, associate dean of students and director of the Markaz Resource Center, which organized the summit.

Muslim Campus Life Summit participants came from universities all over the United States including Duke, Harvard, Howard, Princeton, NYU, San Jose State, the University of Vermont, and Stanford. (Image credit: The Markaz Resource Center) (Image credit: Markaz Resource Center)

But some students may identify as Muslims racially or culturally, instead of – or in addition to – religiously. Serving Muslim students’ non-religious needs has been the province of student affairs offices or offices focused on diversity, equity and inclusion, such as multicultural centers. The Markaz, for example, supports students through a wide array of cultural, social, academic, and mental health and wellness programs, while also undertaking political advocacy such as anti-Islamophobia work.

“Chaplains typically view these issues from a religious and spiritual framework,” said Abiya Ahmed. “The Markaz allows for that – we don’t want students to check their religiosity or faith at the door – but we also bring a DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) framework and research being done on Muslim students. What are the possibilities for serving this community?”

A unique space

The word “markaz” means “center” in multiple languages, including Arabic, Urdu, Hebrew, Turkish and Persian. “It was called this because the center is meant to serve a broad population of students across racial, ethnic, and regional boundaries,” Abiya Ahmed said. “Being Muslim in an American context has so many complexities.”

When Salman Khan came to Stanford in 2016-17 to get a master’s degree in education, he found the range of services for Muslim students — including the Markaz — a pleasant surprise. At his undergraduate institution, for example, there had been no designated prayer area for Muslim students, limited access to halal food, and no Muslim chaplain.

University administrators may not always hear about Muslim students’ needs, said Khan, who is currently a Ph.D. candidate in education policy and program evaluation at Harvard. He is also the co-founder of the Muslim Campus Life project, an advocacy group for Muslim college students. This is partly because many Muslim students come from already marginalized backgrounds.

“There is often an acceptance of the status quo and a lack of self-advocacy,” Khan said.

Tackling tough issues

Summit participants shared the different models for organizing support for Muslim students — and they also tackled hot-button issues. One session looked at external pressures, including Islamophobia and the topic of Palestine. Funding and institutional support also came up during the summit, particularly for public institutions that tend to have less money.

Markaz Associate Director Cassie Garcia and Associate Dean and Director Abiya Ahmed at work inside the center. (Image credit: Micaela Go)

Participants also explored intra-community dynamics, such as gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, and religiosity and sectarianism. The varying needs and experiences within the Muslim student population can make it challenging to make all students feel supported.

“How do we build a supportive community that’s inclusive of this vast diversity on a college campus?” Amer F. Ahmed said.

For example, during Ramadan, some students choose to fast and others do not, Khan said.

“There are close to 2 billion Muslims across the world, so there’s going to be immense diversity,” Khan said.

But Khan said university support can help accommodate all the students who want to participate in Ramadan activities, which tend to happen at night after those who are fasting have broken their fast. It’s important for students to have access to early and late dining hall hours during Ramadan, and for campus security to facilitate the evening events.

The intersection of Muslim students’ needs with the needs of other groups was another complex topic. Gender identity was just one example.

“How does gender identity across a nonbinary spectrum translate into housing and bathrooms and other elements of a campus environment for the purpose of being inclusive – and how does that connect to specific religious obligations that some practicing Muslims and students of other faith backgrounds may understand about their own traditions?” Amer F. Ahmed said. “How can we meet the broadest needs when there may be tensions between what inclusivity looks like for those various identities?”

Looking to the future

The group is talking about holding future meetings, both virtually and in person.

“This cross networking that took place was really momentous,” Khan said. “Providing a space where people could learn from each other has been lacking for a lot of Muslims working in higher education, and hopefully this is the beginning of a change.”