Stanley Yarnell traces his love of art to his childhood, when he and his teachers discovered that he had a talent for drawing. His parents encouraged him by buying him charcoals and instructional books; as a microbiology major in college, he used his electives to take art classes. Years later, he and his partner loved to travel the world, and always they’d visit the major art museums – even though, by then, Yarnell was nearly blind.

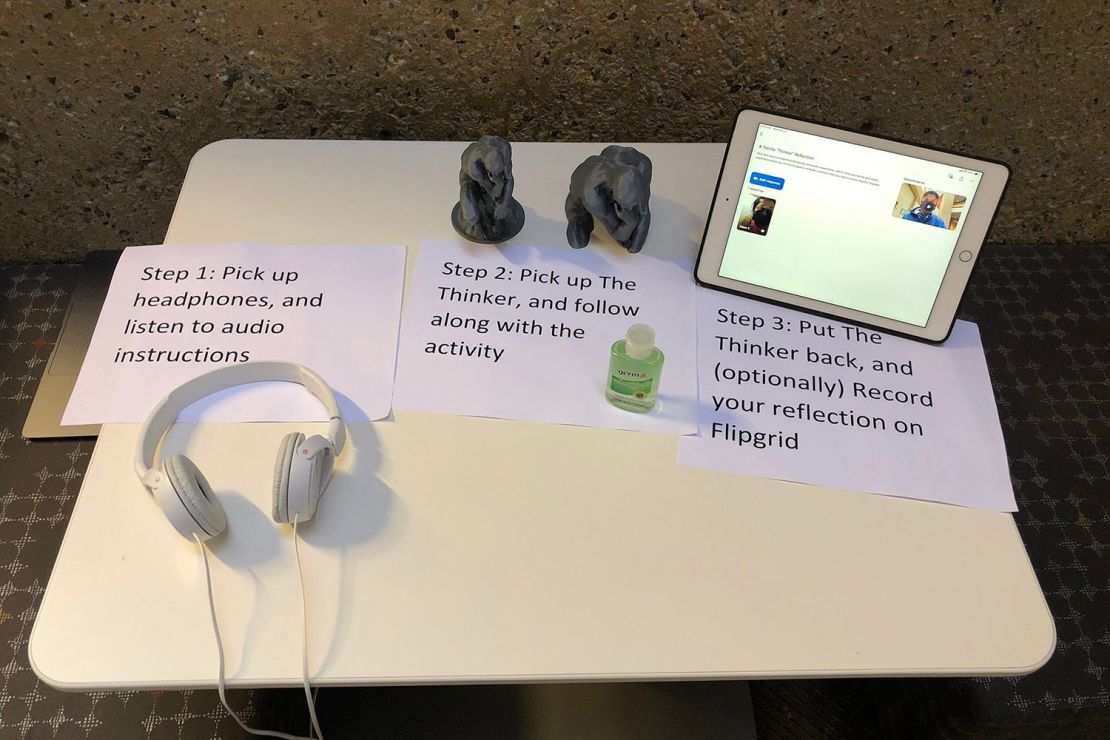

Education students Vicky Z Chan, Rui Huang, and Adam Sparks created a small-scale replica of Rodin’s The Thinker to allow vision-impaired visitors to experience the art through touch. (Image credit: Adam Sparks)

Yarnell, a retired San Francisco physician, started to lose his vision at age 20, the result of a condition called optic neuritis. By 29, he was legally blind, and by age 50 he had lost his sight altogether. But he never lost his love for art.

In 2016, Yarnell founded the Blind Posse, a Bay Area grassroots group aimed at improving access to art for residents who are blind or have low vision. The group has partnered with about a dozen museums, including SFMOMA, the Asian Art Museum, the de Young – and, more recently, the Cantor Arts Center on the Stanford campus.

This past academic year, students in two different Stanford courses – one in the Graduate School of Education (GSE) and another in the School of Engineering – worked with Cantor staff and the Blind Posse to develop innovations for vision-impaired Cantor visitors. Ideas ranged from smartphone apps with audio narration about the art to haptic experiences to a 3D replica of Rodin’s The Thinker that visitors are welcome to touch.

Not all of the ideas can be implemented immediately; in fact, some require technology that doesn’t exist yet. But the students gained robust experience in the design process, from interviewing stakeholders, to generating and testing ideas, to incorporating feedback over multiple iterations. The Cantor acquired a number of new accessibility ideas. And Blind Posse members had an opportunity to share their perspectives with an audience positioned to act.

Applying classroom knowledge to real-world problems

Karin Forssell, a senior lecturer at the GSE and director of the Learning Design and Technology (LDT) master’s program, teaches the course Learning Experience Design, in which students work with community partners on problems identified by the organizations. Forssell works closely with the Haas Center for Public Service on the class, which has earned the center’s designation as a Cardinal Course – a recognition given to courses that apply classroom knowledge to real-world problems.

In two Stanford courses this year, students developed prototypes for ways to make the Cantor Arts Center more accessible to visitors with limited vision. (Image credit: Vicky Z Chan and Rui Huang)

“I’ve always had an interest in including accessibility issues as a component of the course,” Forssell says. “But that really took center stage this past year when we wound up partnering with the Cantor and were introduced to the Blind Posse.”

Two Cantor staffers came to Forssell’s class early in the fall quarter and talked to students about possible projects. By the second week, students were interviewing museum personnel and Blind Posse members; they then brought their findings back to class and began brainstorming, using a whiteboard – and plenty of Post-it notes in assorted colors – to capture their ideas and questions.

By the seventh week, students were taking ideas and prototypes back to their clients (members of the Blind Posse and the museum staff) and collecting feedback. The clients also attended the final presentations at the end of the term.

One group of students used the GSE Makery (which Forssell also directs) to create a small-scale, 3D replica of The Thinker, the one-ton Rodin sculpture that dominates the Cantor’s Diekman Gallery. Visitors are invited to run their hands over the replica and experience the shape of the original, even if they aren’t able to see it.

Another group of students explored the idea of creating a haptic map of the museum that visitors could activate through their own tablets or other devices. (A haptic experience is one that’s based on vibration and touch, and for the Blind Posse, it’s a key way to make art museums more user-friendly.) The idea isn’t mature enough to be implemented yet, but what’s important is that students think creatively and expansively, says Forssell.

“We’re not delivering finished products,” she says. “What we’re bringing to the table is being a thought partner for organizations like the Cantor. We’re digging into something that they care about – something that maybe they don’t have the bandwidth to pay attention to right now, or that they want some fresh thinking about.”

Engineering prototypes with promise

Meanwhile, in the Mechanical Engineering department, adjunct lecturer David L. Jaffe has been teaching a course called Perspectives in Assistive Technology for 16 years. Students in his class also work with community partners, though sometimes the partner is a single individual – a person with cerebral palsy, say, who could benefit from a specific modification to their wheelchair. One team in last winter’s class designed flip-flops for a student who wears a prosthetic leg; another worked to modify a ski pole for a Stanford employee who has a limited range of motion in his left arm.

Like Forssell’s class, the assistive technology class is designated by the Haas Center as a Cardinal Course. And, as in Forssell’s class, students in Jaffe’s class may not address the challenge completely.

“I tell the end user that it may not be suitable; it may be too early; it may break within a couple of weeks,” Jaffe says. “And they all know that. None of them count on what the students did as a necessary part of their life.” In part that’s because a 10-week quarter just isn’t enough time to bring a solution to commercial fruition; the best anyone can hope for is a working prototype.

In Jaffe’s class this past winter quarter, two teams of three students each worked on projects with the Blind Posse and the Cantor. (A total of 44 students took the class; the two Cantor projects were among about a dozen available experiences.) One team, which called itself ArtTech, developed a prototype for a smartphone app that describes the exhibits for museum visitors. (Apps, headsets, and other devices that offer audio descriptions of the art are high on the Blind Posse’s list of best practices for art museum accessibility. It’s not enough to provide narration about the artist’s background or the importance of the work, Yarnell says; instead what’s needed is a physical description of the lines, colors, and textures.)

The other team in Jaffe’s class, who called themselves the Cantor Crew, included journalism graduate student Cricket Bidleman. Bidleman, who is blind, visited the Cantor, and then she and her teammates produced a video about the obstacles she encountered – a floor plan she found confusing to navigate, a lack of Braille or large-print signs, no way to know which exhibits she could touch.

Malika Kanatbek kyzy, MS ’22, a GSE student from Kyrgyzstan, took both Forssell’s and Jaffe’s classes. She enrolled in the GSE’s LDT program specifically because she’s interested in creating educational technology for children with disabilities.

The Cantor project “was perfect for me,” says Kanatbek kyzy, who was part of the team that worked on a haptic approach to navigating the museum; then, in Jaffe’s assistive technology class the following quarter, she helped develop the prototype for the app that describes the museum’s various artworks.

Coming into grad school, Kanatbek kyzy wasn’t sure what kinds of disabilities to focus on in her work. The experience in the two classes helped her narrow her emphasis to visually impaired and blind children, and her master’s project is a web-based platform for helping blind children learn to read and write English.

Moving ideas forward

The students in both classes have moved on to other classes and other projects, leaving the Cantor staff with a trove of ideas to pursue.

“It gives us a database of projects and inspiration that we can work from,” says McKenzie Lynch, academic programs coordinator at the museum. The video produced by the Cantor Crew is particularly helpful, Lynch says, and she has already shared it with a number of Cantor staff. “It shows us the accessibility needs of the museum so that we as staff can better understand what we should be working on.”

Advances in accessibility aren’t just helpful to those with limited vision, Stanley Yarnell points out. For instance, more signs for wayfinding are helpful for any visitor, and audio descriptions of art call attention to details fully sighted visitors might otherwise overlook. Making an art museum easier for blind people to navigate and appreciate, Yarnell says, has a way of enriching the experience for everyone.