Maps are often seen as representations of space, whether that is a particular landscape, planet or cosmos. But maps are equally representations of time, argue Stanford historians Kären Wigen and Caroline Winterer in a new, edited volume. Time in Maps (University of Chicago Press) includes essays from nine prominent cartography scholars who explore over 500 years of world history through maps.

Go to the web site to view the video.

“Maps, the most spatial things we can think of, can play with time in interesting ways that go far beyond our daily representations of time – the clock, the watch, the calendar,” said Winterer, the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “What this book is putting on the table is the reality that time is much more complicated, and that people over the last 500 years understood that. They used this ultra-spatial medium to play with time in really fascinating ways.”

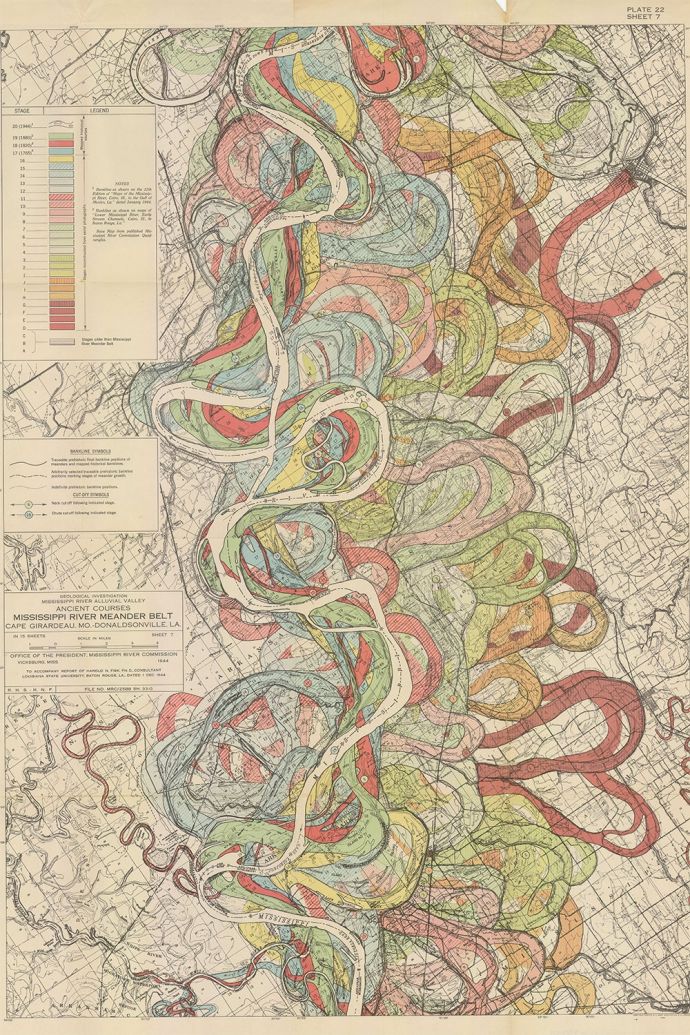

For instance, an image created by the U.S. Geological Survey, on the book’s cover, illustrates the interplay between time and space, showing 4.6 billion years of the Earth’s history in the form of an uncurling ammonite fossil. Another map in the book shows the Mississippi River over the last 2,000 years, with different colors used to represent the river’s position every 100 or so years. The effect is like a work of art, with swirling pastel curves intersecting and overlapping each other as the river meanders, not simply through the landscape but also through time as well.

“Most maps function like a snapshot, with the camera’s aperture held open for a certain period of time,” Wigen said, referring to the Mississippi River map. “This one operates more like memory, with recent layers obscuring older ones.”

Including over 100 color maps and illustrations, as well as essays by Wigen and Winterer, the book grew out of the 2017 “Time in Space: Representing Time in Maps” conference. Organized in conjunction with and hosted by Stanford Libraries’ David Rumsey Map Center and the Stanford Humanities Center, the conference brought together senior scholars and curators to explore how time is conveyed through the representation of geographical features. The map center houses one of the largest cartography collections in the world, donated by San Franciscan David Rumsey.

“History is often defined as change over time,” said historian Abby Smith Rumsey, who wrote a foreword for the book. “Time is a mental construct that cries out for visualization, as this book so amply demonstrates. The variety and originality of contributions to this volume is a leading indicator of how maps used as primary sources open entirely new perspectives into multiple disciplines.”

Organized geographically, the maps in the book are drawn from across the world, including China, Japan, Korea, pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, Europe and the United States. The scholars focused on the period after about 1450 when maps rapidly multiplied in quantity, variety and distribution and moved from being the purview of elites to ordinary objects used and acquired by travelers, soldiers, merchants, explorers and bureaucrats.

The meanders of the Mississippi River over the last two thousand years, with each color showing the river in a different position roughly every hundred years. (Image credit: Harold N. Fisk, Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River (Army Corps of Engineers, Dec. 1, 1944), plate 22, sheet 7. )

“Maps have existed since the earliest human societies; some cartographers would say that no human society has ever been truly map-less, for even the fingers of the human hand can become the bays and peninsulas of a makeshift map,” Wigen and Winterer write. “But the period after about 1450 witnessed an unprecedented flowering of maps. The Scientific Revolution, appropriations of classical mapping techniques, the printing press, burgeoning trade routes – all these factors and more drove the proliferation of cartography worldwide.”

The book also focuses attention on how maps can be used to document non-physical elements of our world including language, describing how the notion of languages as conceptual maps was of great importance in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. These taxonomies were considered crucial to the disciplines of philosophy and natural philosophy.

Essays in the book also address a major debate in the field about the value of traditional physical maps in the era of digital mapping, positing that there is an important role for both. GIS (Geographic Information Systems) has become a powerful tool for investigating maps, as well as other sources of information. The Rumsey Map Center, which is celebrating its fifth anniversary this year, was designed to facilitate both types of research, with large, high-resolution screens and smaller touch screens that allow scholars to enlarge and juxtapose maps to make comparisons and examine details.

The Rumsey Map Center, along with Branner Earth Sciences and Map Collections, which is the other map library on campus, has close to 200,000 catalog records that represent over 300,000 maps. The vast majority of the center’s maps that are in the public domain or not under copyright are scanned, and high-resolution versions are available online to the public free of charge.

“The idea of the Rumsey Map Center is to co-locate the physical, paper-based item with the digital item,” said G. Salim Mohammed, head and curator of the center. “Professors have really taken advantage of that aspect, to be able to view these maps, to lay them one on top of another using high-resolution screens, and then to come back and huddle over the actual physical thing that may be 400 years old.”

The Rumsey Map Center will host a book launch event on Friday, Jan. 22. The event is open to the public with prior registration.

Publication of Time in Maps was supported by David Rumsey and Abby Smith Rumsey.

Media Contacts

Joy Leighton, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: joy.leighton@stanford.edu