Today, the average American is unlikely to spend time worrying about malaria. Although the disease is commonly perceived to be restricted to other parts of the world, it played a significant role in shaping American history. It even helped turn the tide of the American Revolutionary War by infecting so many British soldiers that General Cornwallis was forced to surrender at Yorktown.

The painting, The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull, is on display in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. The surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781 marked the last major campaign of the Revolutionary War and was brought about in part by British soldiers contracting malaria. (Image credit: Artist John Trumbull, courtesy Architect of the Capitol)

First-year students in a 2019 introductory seminar class led by Erin Mordecai, an assistant professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S), delved into this and other historical examples of how vector-borne diseases – those caused by infectious pathogens spread by living organisms or “vectors” – influenced human history. Throughout the course, they collaborated on a paper highlighting various trends in which these illnesses impacted historical societies. Their findings have now been published in the latest issue of the journal Ecology Letters.

“The mechanisms and consequences of vector-borne diseases are multimodal and far more pervasive than we had previously thought,” said Tejas Athni, a student in the seminar and first author of the paper.

As Athni and his fellow students conducted their research, they discovered recurring themes across societies throughout time. One theme was that diseases don’t affect all populations equally – a simple fact that had major ramifications throughout history. In the case of the American Revolution, many Americans had grown up in the South and were exposed to malaria young, allowing them to develop immunity. This granted them a strategic advantage over the less immune British army, which ended up being decimated by the disease.

A more sobering trend unearthed by the group’s investigations was that disease tended to prey on inequities in societies, leaving marginalized groups most at risk. Both intentionally and unintentionally, it was weaponized time and again to enforce unjust hierarchies of power. In the American South, for instance, enslaved Black people were often forced to work in conditions that left them exposed to mosquitoes and made them much more vulnerable to malaria. To make matters worse, this inequity was used by white people to encourage the racist belief at the time that Black Americans were morally inferior and to justify Jim Crow segregation laws in the South.

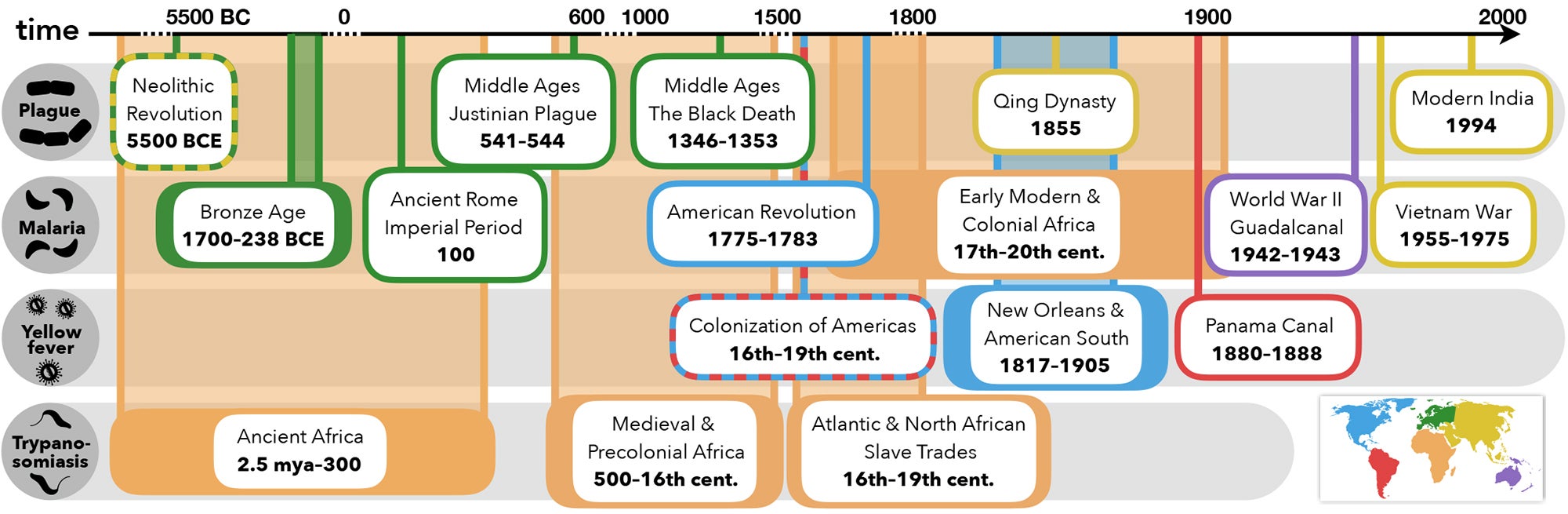

A timeline showing major outbreaks of four vector-borne diseases throughout history. (Click to enlarge) (Image credit: Courtesy Erin Mordecai)

Racism and disease

When Mordecai first submitted her class’s paper for journal publication, it was rejected, with one reviewer citing the paper’s failure to explore the relationship between racism and disease. Taking a more interdisciplinary approach, Mordecai then invited the reviewer, Nita Bharti, the Huck Early Career Professor of Biology at Penn State University, and Steven O. Roberts, an assistant professor of psychology in H&S and a race scholar, to speak to her class about systems of inequality from psychological and historical standpoints.

“We were taken aback by the extent to which the impacts of vector-borne disease have historically splintered across racial and societal lines,” said Athni.

Structural racism, including what neighborhoods people can live in and their access to intergenerational wealth, is linked to disparities in rates of diabetes, hypertension and other chronic diseases associated with stress, Mordecai explained. These disparities are also apparent in the COVID-19 pandemic, where the disease’s outcomes are more serious for individuals suffering with these conditions. This disproportionate burden further amplifies the vulnerability of already disadvantaged communities.

“When you layer on an emerging pandemic with existing health disparities, it disproportionally affects Black and Hispanic communities,” said Mordecai.

Racial disparities also put historically marginalized communities at greater risk of being exposed to the virus. These communities, for instance, are more likely to be essential workers, lacking the luxury to safely shelter in place or have their groceries delivered.

“It’s easy to think that communities of color aren’t social distancing enough or not practicing proper hygiene,” said Roberts, who is a co-author on the paper. “But that thinking completely neglects the social conditions that have made those communities more vulnerable to begin with.”

The relationship between COVID-19 and structural inequality is unfortunately not limited to just modern times or the U.S. This too is a pattern that has repeated throughout history and across the globe. Outbreaks of leishmaniasis, a vector-borne disease spread by phlebotomine sand flies, have impacted hundreds of thousands of Syrians within refugee camps, a result of overcrowding in areas with poor sanitation. And when the first few cases of the Ebola outbreak popped up in 2014 in Africa, scientists in the United States were slow in finding ways to combat it until it showed up closer to home.

The authors hope that this paper will motivate scientists to be more proactive in protecting people in historically disadvantaged communities from disease.

“The paper does a spectacular job documenting the problem,” said Roberts. “Now it will be important to maintain an interdisciplinary focus that can dismantle it.”

Centering equity

Mordecai believes the paper produced as a result of her class is unique in the ecological literature. As the work underwent the peer review process, editors originally commented that it didn’t feel like an ecological study at all. However, since the Black Lives Matter protests in the spring of last year, she said she is seeing a growing number of epidemiologists recognizing the role of racism in infectious disease transmission.

Athni, now a junior working on his honors thesis on statistically modeling the effects of climate on global mosquito distributions, said that being involved in this project has influenced the way he conducts research as a growing biologist.

“Dr. Mordecai’s freshman seminar shaped my entire Stanford journey through an interdisciplinary lens,” Athni said. “Moving forward, it’s imperative that research explicitly recognizes and combats the structural racism, classism and sexism that continue to perpetuate environmental and health inequities. Equity must be brought to the center of ecology and global health in order to make meaningful progress for all of humanity.”

Additional Stanford co-authors include Giulio A. De Leo, professor of biology and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment; Kathryn Olivarius, assistant professor of history; postdoctoral scholar Devin Kirk; former postdoctoral scholars Marta Shocket and Jamie Caldwell; graduate students Lisa I. Couper, Nicole Nova, Marissa Childs and David G. Pickel; and undergraduate and former undergraduate students Julian Cheng, Elizabeth A. Grant, Patrick M. Kurzner, Saw Kyaw, Bradford J. Lin, Ricardo C. Lopez, Diba S. Massihpour, Erica C. Olsen, Maggie Roache, Angie Ruiz, Emily A. Schultz, Muskan Shafat and Rebecca Spencer. Shocket is also affiliated with University of California, Los Angeles, Caldwell is also affiliated with University of Hawaii at Manoa and Kirk is also affiliated with the University of British Columbia. Researchers from James Cook University, University of California, Santa Barbara, University of California, Davis and Penn State University also contributed to the paper.

This research was supported by the Stanford Introductory Seminars Program, National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, the Helman Scholarship, the Terman Fellowship, the King Center for Global Development, the Huck Institutes for the Life Sciences at Penn State University, the Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship program, the Stanford Data Science Scholars, the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies, Global Development and Poverty Initiative, the Stanford Graduate Fellowship, the Ric Weiland Graduate Fellowship in the Humanities and Sciences.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Media Contacts

Ker Than, Stanford News Service: (650) 723-9820; kerthan@stanford.edu