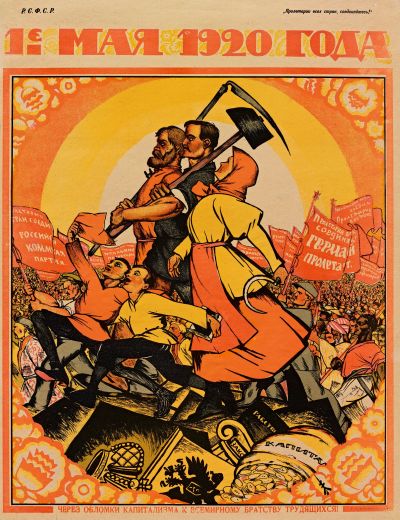

Drafts of the last Russian czar’s abdication letter, painted portraits of Russian rulers from the 18th and 19th centuries, photographs of massive street demonstrations in Petrograd and Moscow in 1917, and early Soviet-era propaganda posters – these are just some of the artifacts on display at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives and the Cantor Arts Center as part of a new exhibition marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Go to the web site to view the video.

The Crown under the Hammer: Russia, Romanovs, Revolution, which runs through March 4, highlights Hoover’s rich collections of artworks, archival documents, photographs and rare books related to late imperial and early Soviet Russia. The Hoover Institution Library & Archives partnered with the Cantor Arts Center to create the special joint exhibition.

The year 1917 saw the fall of the Romanov dynasty, which had ruled Russia since 1613, and the seizure of power by the Bolshevik Party (later called the Communist Party). Under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, the newly established Soviet government fought off its rivals in a bloody civil war, which was followed by a catastrophic famine that killed millions.

What happened then in Russia affected the rest of the world, politically and culturally, said Bertrand M. Patenaude, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and an expert on Russian history who served as a co-curator of the exhibition.

Image credit: Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Image credit: Hoover Institution Archives

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: Nikolai Aleksandrovich Bazili papers, Hoover Institution Archives

Image credit: Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Image credit: Hoover Institution Archives

“The Russian Revolution set off tremors around the world,” he said. “What we get after it is something new under the sun – a Marxist-Leninist regime that really wants to overturn the world. The idea is not simply to stop with Russia but to spread the revolution through Europe and then around the world.”

The Hoover Library & Archives began as a collecting point for documents about World War I and what led to it. In the early 1920s, Stanford historian and Hoover curator Frank Golder spent nearly two years in Soviet Russia collecting materials related to the Russian Revolution.

As a result of that effort and the steady gathering of additional materials in the century following, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives now houses a unique trove of materials on late imperial and early Soviet Russian history, Patenaude said.

“Hoover’s library and archival collections on modern Russia are really unmatched outside of Russia,” he said. “Arguably what draws most researchers to the Hoover Archives are its Russian and East European collections.”

Assistant archivist Samira Borgozi readies a display case at the Herbert Hoover Memorial Exhibit Pavilion. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

To create an exhibition appropriate to the centenary of the Revolution, the organizers sifted through materials in dozens of Hoover collections. The Crown under the Hammer showcases some rare archival gems, such as the abdication drafts. Several oil paintings by Russian masters are on public display for the first time, as part of the Cantor venue of the exhibition.

Inside a gallery at the Cantor, rare one-of-a-kind paintings crafted according to time-honored academic standards hang on the wall opposite groundbreaking, mass-produced posters of the early Soviet era. The juxtaposition underscores the dramatic shift in cultural and artistic priorities sparked by the Revolution.

“It’s impossible for me to look at early Soviet posters and other works supported by the new state and not focus on aesthetic and thematic innovations that would become the hallmarks of 20th-century modernism,” said Jodi Roberts, the Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Curator for Modern and Contemporary Art at the Cantor and a co-curator of the exhibition. “So many approaches to art-making that we look at today and call modern find their roots in the Russian Revolution.”

Roberts said the abundance of Hoover’s Russia-related materials and the collaboration between the Hoover and the Cantor made possible an especially vivid presentation of this striking cultural and artistic shift.

“Exhibitions about the Russian Revolution tend to focus on one side or the other – the Romanovs or the Soviets,” Roberts said. “So it’s really remarkable to have this trove of information and objects that represents both sides of the revolution.”

The two halves of this exhibition, at the Hoover and the Cantor, offer visitors an opportunity to experience the Revolution in ways impossible through books and other after-the-fact analyses of the event and its aftermath.

“There is a difference between understanding historical events through art objects and primary source documents compared to secondary sources,” Roberts said. “These primary materials put you in the time and space of historical events in a visceral and immediate way.”