Daily headlines emphasize the down side of technology: cyberattacks, election hacking and the threat of fake news. In response, government organizations are scrambling to understand how policy should shape technology’s role in governance, security and jobs.

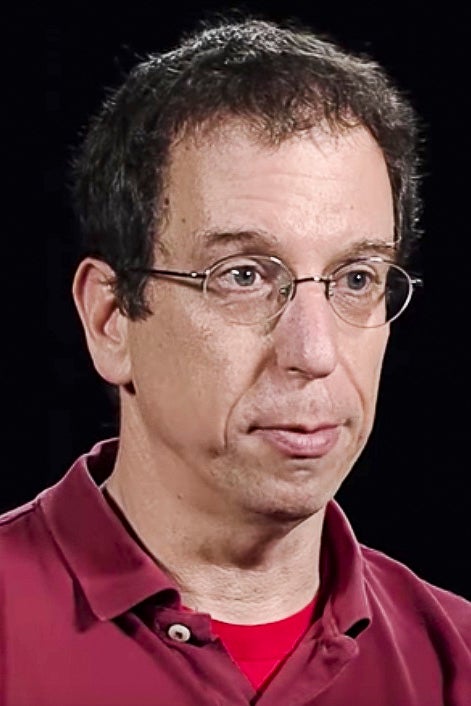

The Stanford Cyber Initiative is at the forefront of answering this question. Co-directors Michael McFaul, a professor of political science and director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI), and Dan Boneh, a professor of computer science and electrical engineering, tell us how the research behind the initiative helps define the role of policy in a world increasingly influenced by technology.

What is the goal of the Stanford Cyber Initiative?

McFaul: It is part of a broader cyber initiative that the Hewlett Foundation started several years ago. New technologies are changing the way we view security, the way we govern, the way we work. They’re part of every aspect of life, and yet how we manage them, how we think about policy to regulate and enhance their use, has not caught up to the technology. Here at Stanford, we’re focusing on the right policies and policy frameworks to address the new technological era we live in today.

Boneh: When we came to define cybersecurity, it turned out to include many different areas. It has to do with the security of computing technology, but it also includes implications to the workforce and U.S. economy. It includes security of our democracy and election systems. It includes security of our financial systems. The Cyber Initiative funds Stanford research in these areas that focuses on policy.

What’s changing now that the Cyber Initiative has moved to the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies?

Boneh: I think it’s wonderful the Cyber Initiative now has a home. With FSI, we have much more infrastructure support. It is also wonderful to have Mike’s vision and leadership for the initiative. Mike has been a fantastic collaborator to work with on this.

McFaul: As the co-director with Dan, we’ve shaped it in a couple of different directions. We want to build on some strengths, and that means fewer areas that we focus on and greater resources to them. The three that I think are most prominent in our thinking are cybersecurity, governance and the future of work.

How does the Cyber Initiative address policy concerns?

McFaul: We require that all projects have an applied or policy component. We’re trying to bridge the gap between the east side of campus and the west side. We want to see more computer scientists interacting with social scientists, lawyers and even philosophers, as there are many ethical and moral issues that need to be addressed.

For example, Amy Zegart and her team at the Center for International Security and Cooperation and the Hoover Institution hosted the Cyber Boot Camp. They assembled congressional staffers who deal with cybersecurity issues as well as other experts to discuss the most pressing challenges in cyberspace. What could be a more direct impact than educating them about these topics? In the realm of disinformation, a consortium of researchers affiliated with the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law are investigating the role that foreign governments played in our election, exploring what regulations should look like and the difference between First Amendment rights and foreign interference.

Then, there is wide disagreement about whether artificial intelligence is going to make us all better off or whether it’s going to make us all unemployed. Scholars supported by the initiative are trying to address this. Understanding the relationship between new technologies and the workforce will eventually help federal, state and local government officials, as well as companies, schools and trade unions, to develop appropriate policies.

Boneh: On the technical side, many new technologies that can be beneficial to end users are not adopted because they do not match companies’ incentives. Good tech policy can incentivize companies to adopt those beneficial technologies that improve privacy and security for clients or consumers. We want policies that promote computer security, but at the same time, we do not want to stifle innovation or greatly increase operating costs. At Stanford, we are in a unique position to make progress on these issues. We have a strong collaboration with the tech industry and the ears of policymakers in D.C.

Why is it important to work across disciplines when addressing cyber concerns?

Boneh: It brings together researchers who normally do not interact much. Every project that we fund crosses school boundaries. It brings faculty in the humanities to work with faculty in engineering, and that is not something that happens very often. You cannot do policy without understanding technology and effective technology needs to understand the policy implications. I recently taught a class with colleagues at the law school on cyber policy and the law. This is not something I would have done had it not been for the Cyber Initiative.

McFaul: Virtually every field is being impacted by new technologies, but expertise in cyber policy is not easily defined. I can tell you which are the five top journals in my field of political science – and if you want to advance your career, you publish there. I’m not sure I could name them in cyber policy. It feels to me like the technology is ahead of the policy, and a lot of the traditional security experts are not well-versed in computer science and engineering, including me. Conversely, those most expert in cyber technologies have paid little attention to national security, democracy or the future of capitalism. By bringing these researchers together, we increase understanding of technology’s role across fields.

How is the Cyber Initiative educating Stanford students?

McFaul: There is growing demand for courses that cross disciplines to address the rapidly evolving landscape of cybersecurity. We are training the next generation of leaders who will shape this field. Some of our new classes focus on cybersecurity and the law, fake news, privacy policies, how algorithms affect human perception, Facebook’s foreign policy, and how technology affects elections. What’s striking to me is that we’re still in the early stages of incorporating cyber components into courses, curriculum and degrees.

Here at FSI, we have a master’s degree in international policy studies, which will soon launch a new specialization in cyber policy. It will be one of the first in the country. But what is the content of such a program? It turns out that’s a pretty contentious issue and we’re wrestling with it right now.

The Stanford Cyber Initiative plans to fund research on cyber policy. Interested researchers should contact Allison Berke at aberke@stanford.edu.