Stanford University Libraries has recently acquired a large collection of historical materials documenting the discovery and exhibitions of the giant sequoia trees between the 1850s and early 20th century.

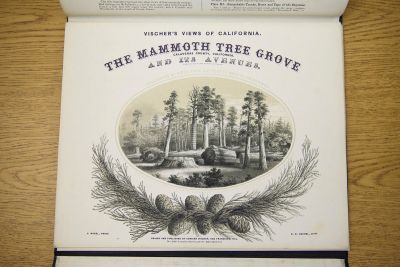

The collection, which was assembled by Livermore-based hydrogeologist and independent scholar Gary D. Lowe, contains over 4,000 items gathered over more than 20 years. It includes printed materials, lithographs, photographs, manuscripts and artifacts made out of the giant sequoia’s wood.

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Ben Stone, curator for American and British history and associate director of Special Collections at Stanford Libraries, said the acquired materials can contribute to teaching and research on American history, environmental and conservation studies, and climate change, as well as art history and many other subjects.

“This collection is as valuable as it is unique,” said Richard White, a professor of American history. “No scholar who is interested in how species become iconic and morph into natural treasures can afford to ignore it.”

History of the Big Tree

Giant sequoias, which are native to the western slopes of California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, are the world’s largest single trees by volume and are among the oldest organisms on Earth. They can live more than 3,000 years, according to the National Park Service.

Native American tribes in California have known about these trees for centuries, but the rest of the world was largely unaware of giant sequoias until they were observed in the 1850s in the area now called Calaveras Big Trees State Park, about 75 miles east of Stockton.

“The giant sequoia trees represented the majesty of the West,” said Stone, who helped acquire the collection. “European Americans at that time had never seen anything like these giant trees in their lives.”

Following these initial discoveries, individual trees were cut down and parts of their trunks, including bark, were transported to exhibitions around the world, with the first one occurring in 1854 in New York City.

Concerns over the conservation of giant sequoias soon emerged. In 1890, the federal government established Sequoia National Park, which is the second oldest national park after Yellowstone National Park.

William Russel Dudley, a Stanford professor of botany from 1892 until his death in 1911, was an early preservationist and dedicated a part of his career to the study and protection of the giant sequoia and the coastal redwood, a species closely related to the giant sequoia. His work contributed to the creation of the Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

Thousands of photographs, century-old artifacts

The new collection boasts many rare items, but a chief hallmark is a set of over 3,400 photographs, of which about 2,000 are stereoviews, or images that appear three-dimensional with the help of a stereoscope.

The photos depict trees and scenes from many of the 68 distinct groves of giant sequoias with images from well-known photographers Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, C.L. Pond and Alfred Hart. Several images capture the Calaveras Grove, including some photos that show the Pioneer Cabin tree in Calaveras Big Trees State Park. The tree, famous for its hollowed-out tunnel, fell in January during a storm. The collection also includes images of the exhibitions showcasing the giant sequoia in cities around the world, such as New York and London.

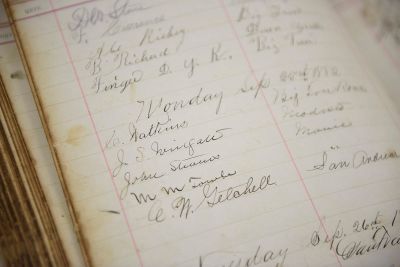

Another highlight of the collection is an original hotel register from the Murphys Historic Hotel in Murphys, California, where tourists flocked after the publicized discovery of the trees. The large manuscript details the names of visitors who stopped at the hotel between 1881 and 1888 on their way to see the Calaveras Big Trees Grove. Among the visitors were Nobel Prize-winning physicist Albert Michelson and British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace.

The collection also holds one of only five known copies of an eight-page 1854 pamphlet, which was the first known publication – aside from newspaper articles – that was devoted to describing the giant sequoia. Among some of the artifacts in the collection are a cigar box and a cane made out of sequoia wood that were displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

Once cataloged, the materials will be available to researchers in the Department of Special Collections at Green Library.

Among the Stanford faculty expressing excitement over the acquired collection and its potential is Devaki Bhaya, a professor, by courtesy, of biology. She teaches a freshman course called Party with Trees, which studies the trees on Stanford’s campus. She said she could use the archives in her future classes.

“Sequoias are so iconic for Stanford and are scientifically fascinating,” said Bhaya, who is also a scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science. “The richness and completeness of this collection lends itself to an interdisciplinary approach to teaching and research.”

Media Contacts

Gabrielle Karampelas, Stanford University Libraries: gkaram@stanford.edu, (650) 492-9885

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: ashashkevich@stanford.edu, (650) 497-4419