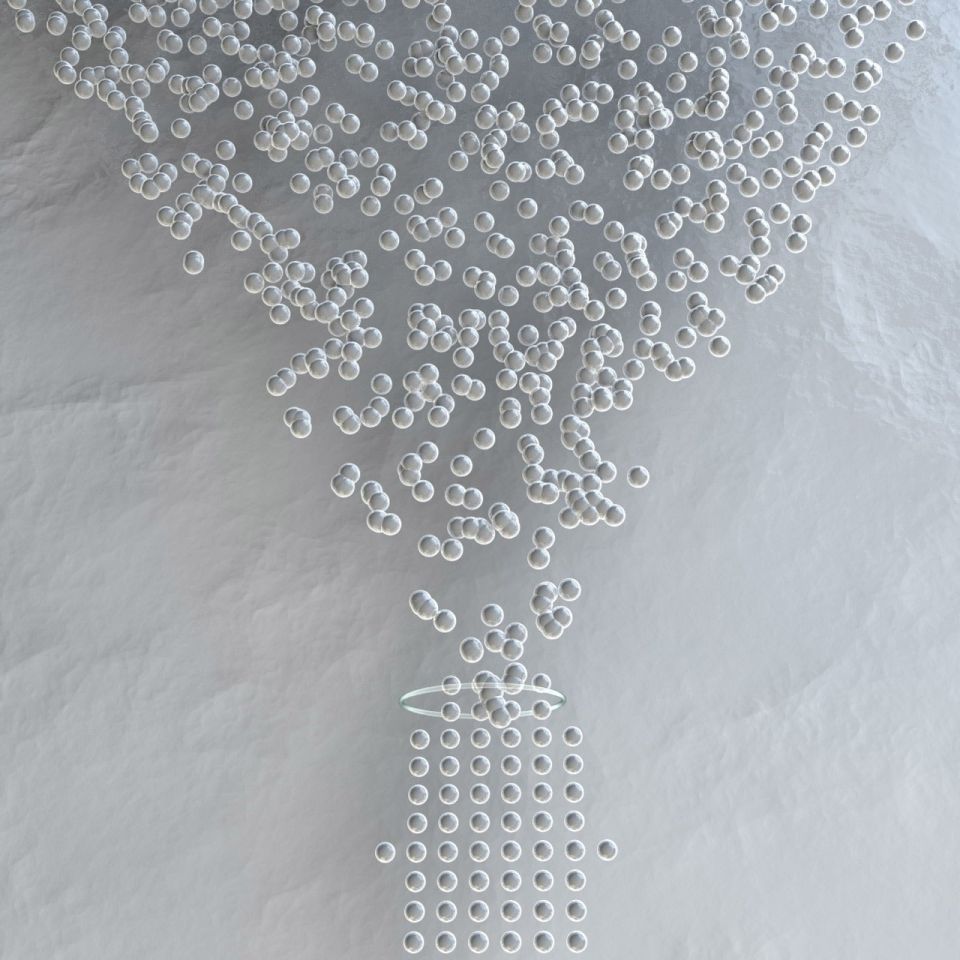

Scientific discoveries often arise from noticing the unexpected. Such was the case when Stanford researchers, studying a tiny device that has become increasingly important in disease diagnostics and drug discovery, observed the surprising way it funneled thousands of water droplets into an orderly single file, squeezing them drop by drop, out the tip of the device.

Stanford mechanical engineer Sindy Tang found order in the seemingly random process of how droplets move through narrow spaces. (Image credit: Ella Maru)

Instead of occurring randomly, the droplets followed a predictable pattern. These observations led graduate student Ya Gai and Sindy K. Y. Tang, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering, to deduce mathematical rules and understand why such rules exist. The work was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It all started with an effort to design tiny devices called microfluidic chips, designed to automate and expedite biomedical research. In the past, lab experiments involved using a dropper to deposit biological specimens into a test tube for observation. But microfluidic devices work much more efficiently. About the size of a postage stamp, they are made of silicone containing many thin channels through which researchers can pump tiny amounts of fluids. The devices allow researchers to place a specimen into a droplet of water surrounded by a thin film of oil. That droplet becomes the test tube. The oily film keeps each droplet and specimen separate.

The microfluidic chips developed in the Tang Lab can create millions of these specimen-bearing droplets quickly. The steadily streaming droplets are ultimately funneled in single file past an instrument that peers at the specimen inside the droplet.

“While studying the flow physics of the droplets in the funnel, we observed that, contrary to our expectations, the droplets juggle past each other in a very orderly manner as they squeeze from the wide end to the narrow end of the funnel, which can fit only one drop at a time,” Tang said.

The team saw packs of drops sliding against each other, something that is more typically seen in solid crystals. ”That caused us to consider concepts from solid mechanics,” Tang said. She invited Wei Cai, another mechanical engineer who studies how atoms move in crystals, to join the effort.

Sindy K. Y. Tang (Image credit: Rod Searcey)

“Stanford Mechanical Engineering is a great place to be as the environment promotes collaborative efforts, in this case between microfluidics and solid mechanics,” Tang said.

While water droplets are squishy and metals seem solid, if you zoom past what is visible, tiny droplets coated in oil bear some resemblance to metal atoms wrapped in electron clouds.

“They both occupy space,” Cai said. “You can’t put two atoms or two droplets in the same spot.” The researchers found that when force is applied – such as when microfluidic pressure is used to force droplets through the funnel – they squeeze against each other and move according to the laws of mechanics.

When crystals are deformed, defects called dislocations form and move through the lattice to shuttle the atoms around. It turns out that the periodic pattern of droplets is the result of dislocation dynamics that also occur when crystalline solids are deformed.

Droplets form an orderly line as they squeeze through a narrow opening. (Image credit: Ya Gai)

“Beyond the immediate relevance to microfluidics, we believe our findings could one day be applied to forming nanocrystals into precise shapes,” Tang said. Researchers do not yet have a way to exert the sort of steady pressure on metal atoms that microfluidic chips can do with oil-separated water droplets.

The corresponding process for metal forming is called extrusion – it’s also what happens when we press the wide end of the toothpaste tube to deposit a dab on our brush. If technologists find a way that could extrude atoms through a nanoscale channel, one could imagine the atoms funneling along as do the water droplets in the microfluidic channel.

And if or when such nanoscale extrusion becomes possible with metallic atoms, this experiment suggests that it may be used to produce nanowires with diameter precision down to a single atom.

“We saw something puzzling, we asked the right questions and we learned something useful not just to the problem we are studying, but also to an entirely different field, in this case how one might go about manufacturing nanocrystals,” Tang said.

An additional author on the paper is Chia Leong, a visiting scholar in the Tang Lab. Sindy Tang is a member of Stanford Bio-X and Stanford ChEM-H. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Media Contacts

Sindy K.Y. Tang, Mechanical Engineering: sindy@stanford.edu

Amy Adams, Stanford News Service: amyadams@stanford.edu, (650) 796-3695