Many people turn to science fiction and fantasy to escape from the real world, but three Stanford University faculty have created a course where such works are being used to inspire students to imagine a better future.

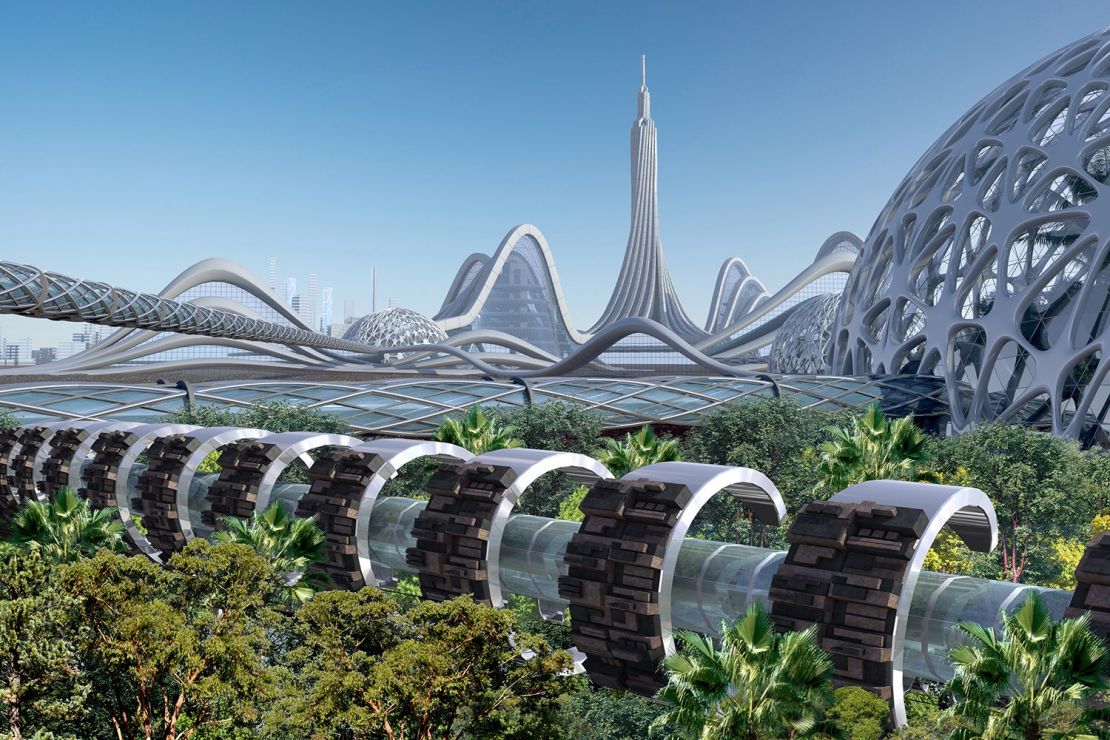

The course Imagining Adaptive Societies used science fiction as a jumping off point for discussing the potential for a better future. (Image credit: Getty Images)

Through engaging with speculative fiction – works that encompass both science fiction and fantasy – faculty members James Holland Jones, Margaret Levi, and Paula Moya encouraged students, and themselves, to think about how people in society could someday adapt to current challenges to create a world that is sustainable, desirable, and just.

“One of the great things about speculative fiction is that, by changing reality in order to create a plausible story about the future, it also comes up with solutions that we may not have thought about,” said Levi, who is a professor of political science in the School of Humanities and Sciences and former director of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, where the course originated.

Common interests and complementary skills

In 2019, Jones, a biological anthropologist in the Doerr School of Sustainability, and Levi began this project by planning a workshop for social scientists and writers focused on the science of narrative and how it can help people make sense of an uncertain world. All too fittingly, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted their plans.

But, also on theme, they adapted.

First, Jones and Levi decided to expand to a full course, which they called Imagining Adaptive Societies. The core of the work was reading and discussing a range of novels and short stories that offer varied perspectives on the future from climate science, social science, and literary criticism.

Second, Jones and Levi wanted another collaborator. They realized that, while they had wide-ranging expertise between them – Jones applies a statistical, mathematical approach to his work on human adaptability and disease ecology, and Levi is a social scientist who thinks about history, political problems, and societal issues – they needed someone who was an expert in narrative and writing.

That is where Moya, who is the Danily C. and Laura Louise Bell Professor of the Humanities and professor of English in the School of Humanities and Sciences, came in.

“Between the three of us, there were three very different disciplines and perspectives. It was a lot of fun,” said Moya.

The multi-disciplinary makeup of the topic and instructors was reflected in the participants, who represented several schools across science, social sciences, and the humanities, and ranged from undergraduates to members of the Distinguished Careers Institute (DCI), which focuses on accomplished individuals in mid-life. Authors Kim Stanley Robinson (New York 2140) and Ted Chiang (The Life Cycle of Software Objects) also spoke with the class about their work and ideas.

“Every week, it was something new and interesting and different,” said Jones. For example, a discussion with students pursuing a joint master’s at the Law School introduced him to new legal frameworks for protecting the environment. In another case, one of the DCI students, who produces and writes for TV and films, clarified what climate messaging works (and what doesn’t) for different audiences.

“What I really came to understand is that when you have a very complex phenomenon, no one disciplinary perspective is sufficient for understanding it,” said Moya. “And I think this is the case with climate change right now. So, if we, as a society, are serious about making change, then we have to talk to other people from different disciplines to help us imagine other kinds of solutions.”

A better future

Even with enthusiastic encouragement, it can be hard to dream up a good future from our complicated and often distressing present. And this is true for academics, students, and authors, alike.

“It’s really easy in climate fiction to go down a very dark path,” said Jones. “So, when we’re imagining adaptive futures we’re not denying the challenges. But we’re asking, what would it take to surmount them?”

The instructors plan to offer the course again next winter and are focused on finding more material that bucks the trends of long, somber speculative fiction. With their sights set on a more optimistic future course that embraces complexity, collaboration, and diverse perspectives, Jones, Levi, and Moya are, in their own discrete way, setting an example of their central aim.

“Our biggest hope is in the title,” said Levi, “…that this course gives students a greater capacity to imagine what an adaptive society might look like.”

Jones is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. Levi is also a senior fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and at the Woods Institute for the Environment. Moya is also faculty director of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.