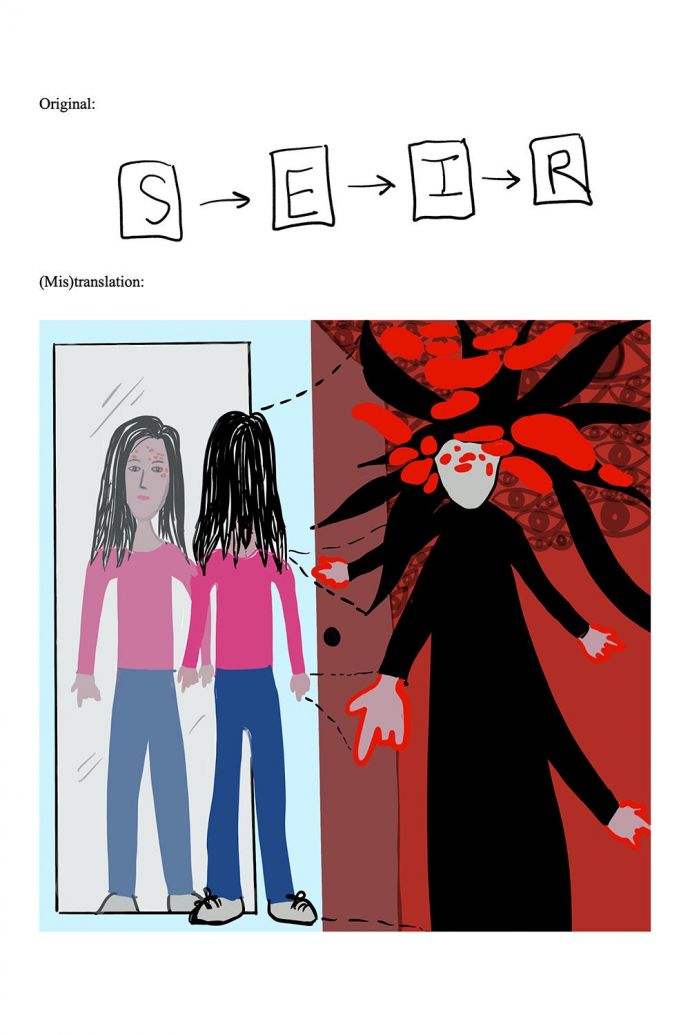

One student knitted an illustration of exponential growth. Another made digital art comparing typical physical symptoms of leprosy to an exaggerated depiction reflecting the social stigma of the disease. Students in Alex Sherman and Mallory Harris’s Pathogens and Populations: Representing Infectious Disease course at Stanford created screenplays and sculptures, poems and political cartoons, all exploring how to translate scientific information into art – and learning the limits of translation.

Gert McMullin, the “mother of the AIDS Quilt” from the National AIDS Memorial, talking with the class on World AIDS Day. (Image credit: Mallory Harris)

“They had to write about the process of representation, and through that, they learned this idea of representational pressures: you’re always going to have to leave something out, and you’re always going to have to choose to emphasize certain things,” Harris said. “They’re starting to think about what the potential consequences of that are, why you would make a certain decision.”

During the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Harris and Sherman began a conversation about how scientists, politicians, and others represent infectious disease to the public. Harris, a PhD candidate in biology, studies the relationship between human activity and infectious diseases. Sherman, a PhD candidate in English, studies the intersections of literature and science in the British empire.

“We keep coming back to this idea of what is the cultural representation good for, what is the scientific representation good for, and how can we use both of them to complement each other to tell a more complete, inclusive story,” Harris said.

Harris and Sherman decided to turn the conversation into a course proposal. This fall quarter, they co-taught Pathogens and Populations, an English elective, for the first time.

The course brings together students across disciplines to explore a central question posed in the syllabus: “How can we comprehend, let alone make meaningful decisions about, complex multi-scale systems of people and pathogens?”

Telling stories with data and art

Every week, students in Pathogens and Populations compared a scientific study or data set with a cultural object.

Tiffany Liu’s visual comparison of typical symptoms of leprosy and an exaggerated depiction of the disease, which reflects social stigma. SEIR stands for “Susceptible, Exposed, Infectious, Recovered,” and is an epidemiological model used to predict infectious disease dynamics. (Image credit: Tiffany Liu)

For the week examining randomness, they played the board game “Pandemic,” then looked at scientific figures representing stochasticity and uncertainty. To understand methods of representing mortality, they compared oral narratives of the Trail of Tears genocide to Cherokee demographers’ estimates of the death rate.

The students were often surprised by the contrasts they found. When they read Welcome to our Hillbrow by Phaswane Mpe, a novel about a neighborhood in post-apartheid Johannesburg, South Africa, that discusses HIV/AIDS, the students were amazed at how well it represented the complex ways disease moves through society.

“When we finally came to this really normative form – the novel – it was like, ‘Oh, wow, this is doing a lot of the stuff that we’ve been looking for in terms of representing individuals and representing populations at the same time,’ ” Sherman said. “It’s representing emotions and feelings and the nuances of disease, but not just the nuances. It’s representing disease as part of a much bigger social system.”

The class looked at several representations of HIV/AIDS because of its local relevance and its global impact on epidemic responses.

Harris and Sherman wanted to end the course with a lesson that would show students what they could do with the insights they gained in Pathogens and Populations. On Dec. 1 – World AIDS Day – they discussed the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Staff members from the National AIDS Memorial, including Gert McMullin, the “mother of the AIDS Quilt,” talked to the class about activism.

“We could think of almost no better example than the AIDS Quilt as something that really made vivid for a lot of people what this epidemic was doing,” Harris said. “We had spoken a lot about how to capture this massive loss and how to deal with having all of these wonderful, complicated lives that are impacted on the individual scale. You want to respect their personhood, but you also have this huge scale of loss.”

Celebrating complexity

At the end of the quarter, Harris and Sherman consider Pathogens and Populations not only a success for the students, but also evidence of the importance of interdisciplinary courses. They are working on a plan to make the class a regular event, and they are looking for other lecturers or faculty members who want to be involved.

Having co-teachers from different disciplines was one of the strengths of the class, Sherman said.

“We’re trying to set up a conversation between science and literature, and we’re actually, literally going to have a conversation between me and Mallory,” he said. “We ask each other questions and follow up with each other in front of the students to show that this is a dialogue. It’s not something where anyone has the answers.”

This message of complexity hit home for Tiffany Liu, a senior English and symbolic systems major and the student who created the art about leprosy. She signed up for Pathogens and Populations because living through a pandemic made her curious about representations of disease.

Before the class, she tended to think of science and culture as a dichotomy. But each discussion, activity, and assignment gave her a greater understanding of their intertwined relationship.

“I think there’s so much that I learned in this class about how you can’t really have one without the other – they both are super essential to people’s understanding of disease,” Liu said. “Even with the two of them together, there’s still so much that can be explored.”