South Korea is a country slightly larger than the U.S. state of Indiana. It has a population of 50 million. And yet its popular culture has gone global. In just the past few months, the television series Squid Game smashed online streaming records, the Oxford English Dictionary added 26 Korean words and the boyband BTS’ appearance at the United Nations 76th General Assembly went viral – these are just some examples of the world’s obsession with Korean cultural content.

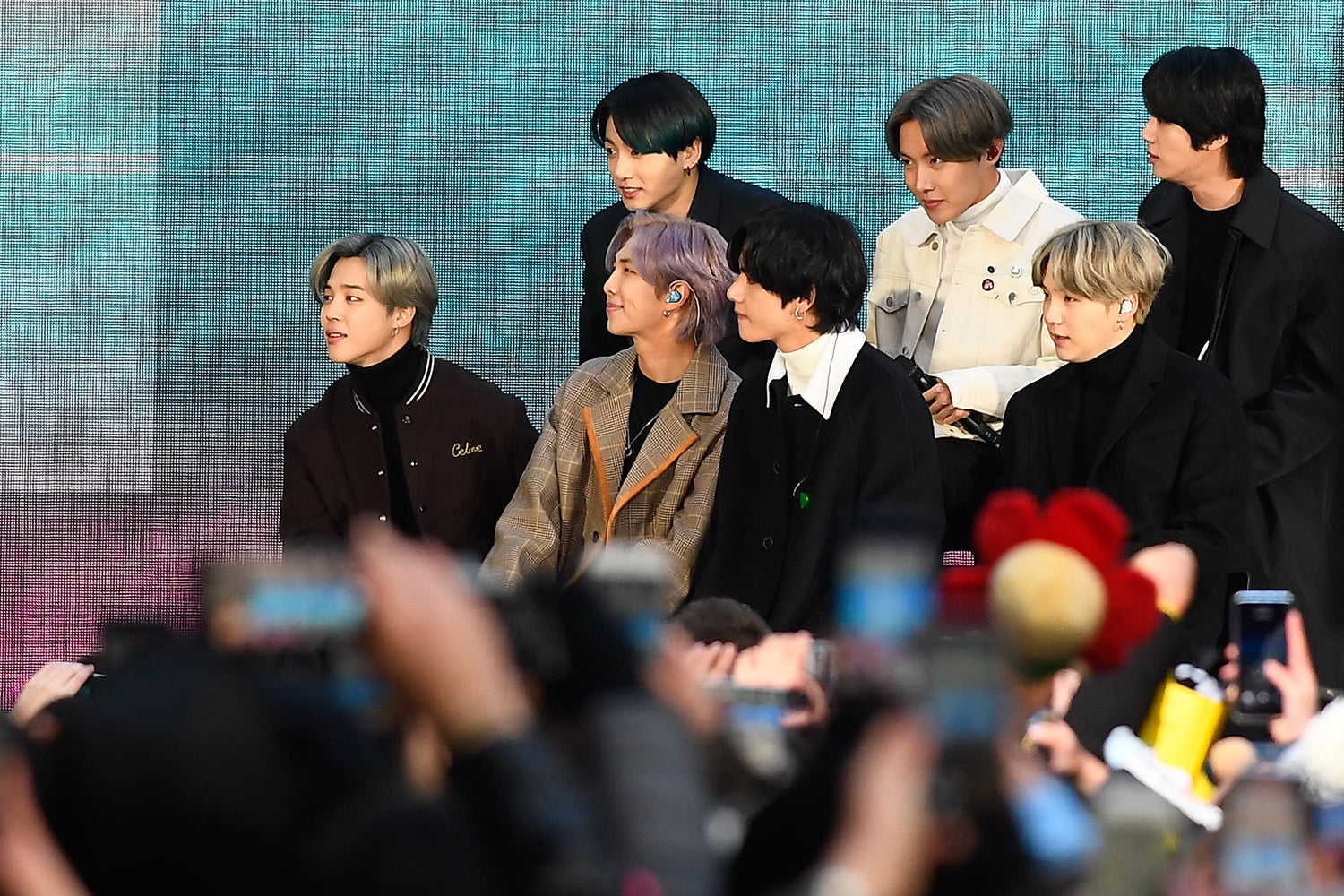

K-pop boyband BTS appears at the Today show on Feb. 21, 2020, in New York City. (Image credit: Raymond Hall / GC Images)

Korean cultural content is popular because it’s really good, says Dafna Zur, an associate professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures and scholar of Korean literature. Zur teaches courses on Korean literature, cinema and popular culture, and is the director of the Center for East Asian Studies at Stanford.

Here, Zur talks about what makes Korean popular culture successful and explains why it appeals to audiences around the world.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

What are some distinguishing features of Korean media, particularly its dramas?

Thanks to streaming platforms like YouTube and Netflix, and to vigorous subtitling efforts – with collaboration by fans, too – Korean pop music and dramas are widely available and easily accessible. Even when the content is in Korean, there are few barriers to entry.

Korean dramas strike a balance of predictability and originality. Their story arcs are often predictable: rags to riches, rich boy meets poor girl, children defy their parents’ wishes and strike out on their own. But they have a Korean twist: Characters are deferential to their elders, sons and daughters are filial. The backdrop is hyper-modern and glitzy. The actors are polished and attractive. They play characters that are charming, vulnerable, and have a healthy dose of self-deprecation. The scripts are full of good humor. Of course, there is often a dark twist: suffocating expectation, crushing poverty, a profound secret that must not get revealed. Korean dramas humanize even the most aloof billionaires and get audiences to care – and usually, all they ask of us is 16 hours of our time.

Korean media pour tremendous resources into their dramas. Dramas are collaborative productions that attend to every last detail to ensure a positive viewing experience that is also wholesome and family friendly. Viewers are assured to get good shots of Korean food, fashion, street life, and gorgeous countryside landscapes.

What about K-pop? Is there a similar formula or secret to its success?

Much of the success of K-pop has to do with the idols at the center. K-pop idols are as close to elite athletes as you will ever get in music talent. They are incredible dancers. They have tremendous charisma. They are disciplined and hard-working. They know how to speak to the camera and they know how to interact with one another in a way that draws in the fans. They maintain squeaky clean images. Their behavior is held up to extremely high standards.

At the same time, they project extreme approachability. They ooze fun and kindness, and they address their fans in ways that come across as authentic. In return, fans are loyal, as loyal to K-pop idols as any sports fans are to their favorite teams. This forms a really interesting dynamic between the idols and their fans.

How so?

Idols take their fans very seriously. Elaborate communication platforms allow K-pop idols to speak to their fans and to acknowledge fans’ role in their idols’ success. Fans are fiercely protective of their idols’ well-being. They reject fans who are too obsessive, like those who deliberately book flights on the same planes as their idols. The bond that is built between idol and their fans is powerful.

BTS, for example, started as underdogs in Korea’s entertainment industry. They lacked the brand recognition of Korea’s larger entertainment companies. Their success had as much to do with the loyalty they cultivated among their fans as with their talent. Their fan base is called Army – all K-pop groups have a named fan group. Army’s enthusiasm – and membership – has only been growing in recent years.

How do your students today who are familiar with Korean culture as a consumer respond to studying the country from an academic perspective? How has the field evolved given the spread of Korean culture abroad?

I first went to South Korea in the early 1990s to get my black belt in taekwondo. I knew very little about the place I was going – I wasn’t aware that Korea had only recently emerged as a democracy, for example. There was still a lot of roughness about Seoul – it was not as polished as it is today. Traffic was a mess. Bus drivers smoked while they worked. Back then I knew little about South Korea other than taekwondo.

By comparison, today’s students have grown up with Korean popular culture. “Gangnam Style” went viral in July of 2012 – that was almost 10 years ago. Some of my students have never even seen the video because they were 8 or 9 when it came out. But they know SuperM, EXO, Blackpink, Girls’ Generation, Seventeen and so many other K-pop groups – too many to mention in one breath.

I find that students are increasingly interested in engaging with Korean culture on multiple levels. They want to learn the language, along with Korean literature, film, history, politics and popular culture. They want to understand how a small country with limited natural resources managed to become a giant economy and influencer in the cultural field. Students also want to understand North Korea and how South Korea can thrive while a nuclear North Korea, just across the border, presents a complex security threat. It is not just South Korea’s issue: North Korea shares a border with China and Russia, and Japan is just across the East Sea. Our students today know what took me years to figure out: Korea holds the key to economic, political and cultural puzzles today. And it is way cool.

Media Contacts

Melissa De Witte, Stanford News Service: mdewitte@stanford.edu