During wildfire season, Californians have become intimately familiar with orange and red skies, worsening air quality and, in some cases, community-wide devastation. But what some people might not realize is that there is much more to wildfire response and prevention than just putting out fires and cutting down trees. As part of the 2020 Big Earth Hackathon, student projects sought to address some of these complexities and two have since been selected for further collaboration with CAL FIRE, the main organization that responds to wildfires in California

Firefighters arrive at the scene of the Dixie Fire, still burning today, which has surpassed over 844,000 acres burned. Stanford student projects could help first responders track and predict fire spread, assess vulnerable communities nearby and plan effective evacuation procedures. (Image credit: CAL FIRE)

“The Big Earth Hackathons aim to come up with innovative solutions for problems that are affecting our planet,” said Derek Fong, senior research engineer and lecturer in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “We recognized that people know a lot less about wildfires than they do about water and other environmental issues. Wildfires are not something you can learn by looking at a one-page blurb on a proposed project. We really needed to expose students to the vast array of problems related to wildland fires, from prediction to prevention, educating homeowners, equity issues or even political ramifications.”

So, Fong, along with collaborator Margot Gerritsen, professor of energy resources engineering at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth), created a companion class to provide hackathon students with more time to work on their projects, as well as a structured environment to learn from visiting industry experts, including members of CAL FIRE.

“The projects don’t involve just looking at satellite images and crunching math and doing coding. There are social studies issues, medical issues, laws and ethics, and policy issues that need to be considered,” said Fong. “All the hackathons we’ve done so far have been very interdisciplinary in nature. These are ‘citizens of planet Earth’ type problems.”

Fong and Gerritsen invited experts from various fields to work with students on their projects, and two student projects stood out in particular for Jay Song, chief information officer at CAL FIRE.

“These Stanford students understand that wildfires are a multidimensional issue,” said Song. “The projects brought new aspects and different dimensions into their solutions because they were not afraid of thinking outside of the box.”

The two projects chosen by CAL FIRE were: Live Interactive Fire Evacuation (LIFE) Tool by Jack Seagrist, Yash Gaur and Hunter Johnson; and Project Firesafe by Hannah Sieber, William Steenbergen, Joanna Klitzke and Will Ross.

Live Interactive Fire Evacuation (LIFE) Tool

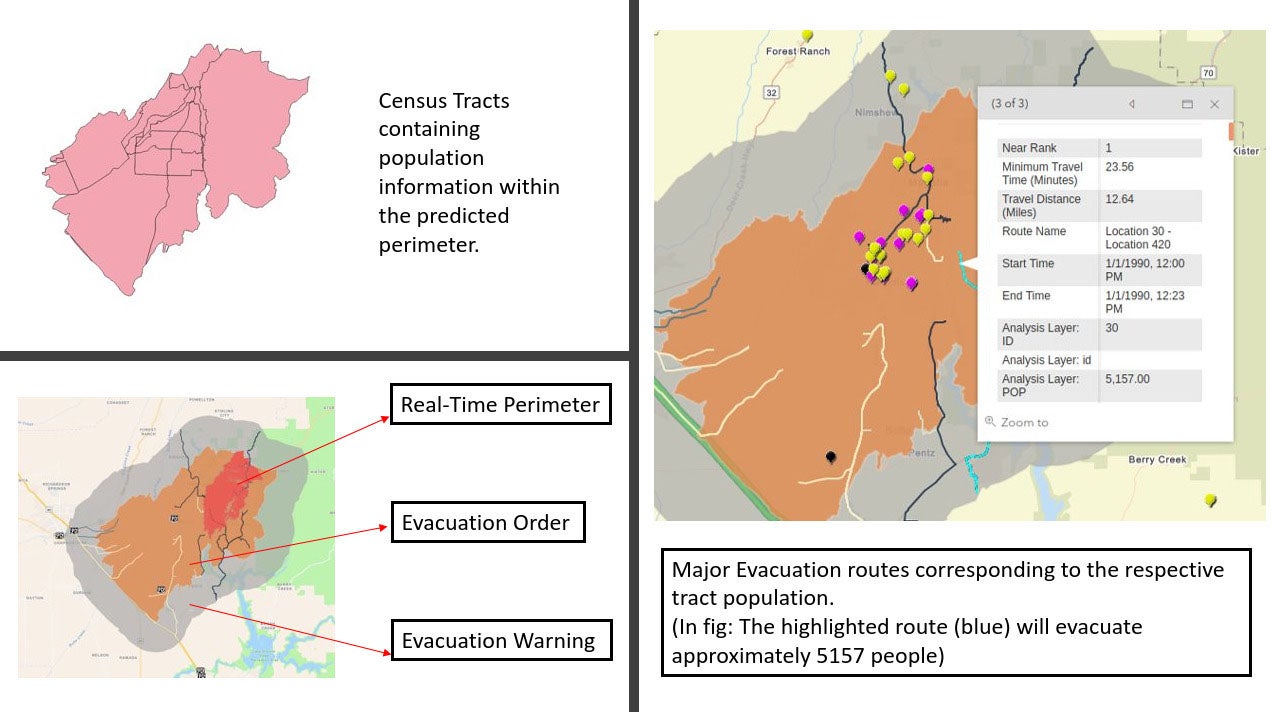

An overview of how the LIFE Tool takes census and traffic data to model evacuation flow on different routes and in various stages of evacuation.

“From some of the talks in class we heard a lot about how some cities in California have evacuation plans while others don’t,” said Seagrist, a graduate of the Stanford master’s program in environmental engineering. “In the event of a fire, there’s really no standardization for these plans, so there are different levels of preparedness and readiness for every city.”

The LIFE Tool team was inspired by this problem and wanted to simulate traffic flow during evacuations. Their tool, which can be used by first responders in the field and by planning committees before a fire, combines fire perimeter and environmental data with traffic and population data to evaluate and suggest the best evacuation routes for various communities.

“This was one of my favorite classes at Stanford,” said Seagrist. “It was really cool to see how CAL FIRE puts a lot of time and effort into different school projects and gets students thinking about solving some of these problems. It’s good not only for managing fires, but also for helping students use some of the skills that we’re cultivating in the classroom.”

Project Firesafe

This screenshot shows what CAL FIRE first responders might see while using the tool from Project Firesafe. The assessment is shown after selecting a custom area on a map, with the scale deeming 10 as the highest social vulnerability risk and 1 as the lowest risk. (Image credit: Hannah Sieber)

Motivated by the interdisciplinary nature of wildfire operations, the team behind Project Firesafe layered social vulnerability data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on top of fire spread models to identify the most at-risk communities in real time.

“The CDC Social vulnerability data is a series of different variables that affect someone’s well-being, everything from income to age to one’s ability to speak different languages. We chose factors that we thought were most relevant to wildfire evacuation,” said Sieber, a master’s student in Stanford Earth’s Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources and Stanford Graduate School of Business.

The tool takes small, half-kilometer by half-kilometer areas, predicts the burn risk using artificial intelligence techniques and then layers in selected social vulnerability factors. The end result is a visualization that any fire responder or response planner might easily use.

CAL FIRE and other response planners could potentially use this data to make crucial strategy decisions. For example, more interpreters could be deployed to neighborhoods where Spanish is the dominant language or more buses and other means of evacuation can be ready in areas where car ownership is low.

“We’re focusing on variables that have clear interventions and strategies that could be implemented,” Sieber said.

Project Firesafe “touched a possible blind spot and pointed out a vital factor that must be considered in the critical decision making of assessing the wildfire risk for communities,” said CAL FIRE’s Song.

Looking to the future of wildfires

These projects are only first steps toward innovations in wildfire response practices, but they are substantial first steps, Song said. Now, the focus is on working more closely with CAL FIRE to put the student ideas into practice and aligning them with the agency’s larger goals.

“One of our biggest goals is to create a fire simulation that can predict where the fire will go in real time and as far as 5 to 6 hours into the future. We would like to have some software that uses AI to monitor our satellite cameras and predict fire spread,” said Song.

CAL FIRE has plans for continuing cooperation with Stanford to further develop AI tools for assessing burn risk and fire spread, Song said.

“Students are very, very passionate. Their goal is to find the problem and its root cause,” he added. “They provide solutions to help us that are very enlightening because they have different angles of approach where CAL FIRE is often busy with too many fires. We’re constantly focusing outward for fire response, but students can look inward from different points of view to help develop better methods.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Media Contacts

Taylor Kubota, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-7707, tkubota@stanford.edu