Former U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz, the Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution and professor emeritus at Stanford Graduate School of Business who served three American presidents and played a pivotal role in shaping economic and foreign policy in the late 20th century, died Feb. 6 at his home on the Stanford campus. He was 100 years old.

Go to the web site to view the video.

One of the most consequential policymakers of all time and remembered as one of the most influential secretaries of state in American history, Shultz was a key player, alongside President Ronald Reagan, in changing the direction of history by using the tools of diplomacy to bring the Cold War to an end. He knew the value of one’s word, that “trust was the coin of the realm,” and stuck unwaveringly to a set of principles. This, combined with a keen intelligence, enabled him not only to imagine things thought impossible but also to bring them to fruition and forever change the course of human events.

Shultz’s extraordinary career spanned government, academia and business. He is one of only two Americans to have held four different federal cabinet posts – State, Treasury, Labor, and Office of Management and Budget. He taught at three renowned universities, and for eight years was president of a major engineering and construction company.

Condoleezza Rice, a fellow former secretary of state and current director of the Hoover Institution, where Shultz served for more than 30 years until his passing, said, “Our colleague was a great American statesman and a true patriot in every sense of the word. He will be remembered in history as a man who made the world a better place.”

Shultz first joined Stanford in 1968 and had periodic affiliations with the university throughout his public service career, finally returning to campus in 1989. Always dedicated to his students and higher education, Shultz tackled some of humanity’s most difficult issues – including nuclear disarmament, climate change and democratic governance – in the classroom, in book and article form, and at events he hosted. Those issues drove him to keep working at Stanford nearly every day until his passing.

“George Shultz was a giant in public policy and world affairs, as well as a dedicated scholar and educator,” said Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne. “He was an extraordinary role model, a consummate bridge-builder in pursuit of the public good even beyond his hundredth birthday. His remarkable life and career serve as an inspiration to all those whose lives he touched at Stanford and beyond.”

‘Defend freedom and preserve peace’

In 1982, Shultz was named secretary of state at a time of heightened global tensions with the Soviet Union. The full measure of his talent at negotiation came when Shultz implemented a foreign policy approach that eased those tensions and led to several landmark arms control treaties. Shultz also served as secretary of labor, the first director of the Office of Management and Budget and secretary of state, all under Richard Nixon.

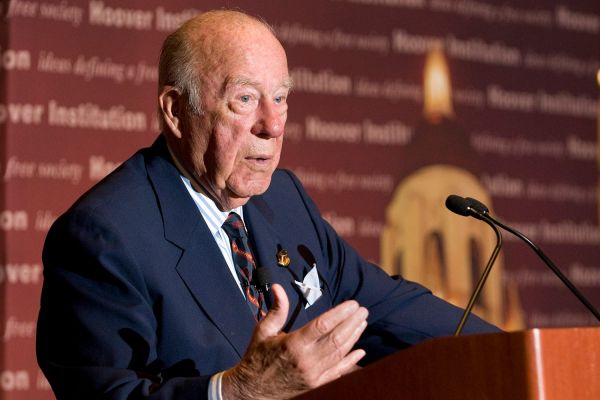

Former Secretary of State George Shultz, a distinguished fellow at the Hoover Institution and professor emeritus at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, shown here in a 2008 photo, died Feb. 6 at age 100. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Shultz was renowned for his patient, credible and remarkably effective approach to diplomacy, most often eschewing the limelight to defer to the presidents for whom he worked. Along with his straightforward style, he had a hard-driving commitment to solving tangled policy problems and avoiding extreme partisan politics.

In particular, the global threat of nuclear weapons deeply troubled Shultz.

“In an age of nuclear weapons, maintaining collective security is no easy task,” Shultz said to Stanford graduates in 1983 when he returned to campus to deliver the Commencement address. “We must both defend freedom and preserve peace. We must seek to advance those moral values to which this nation and its allies are deeply committed. And we must do so in a nuclear age in which a global war would thoroughly destroy those values.”

Shultz was keenly interested in efficient policymaking during today’s era of stunning technological and social complexity. His 2019 book, Thinking About the Future, a collection of his writings and remarks, is a testament to his approach to sound policymaking.

His recent initiative at the Hoover Institution, Governance in an Emerging New World, revealed Shultz’s penchant for open discussions on how governments, institutions and society can best respond to rapid changes. He hosted about a dozen “governance” events on the Stanford campus starting in 2018 and in November 2020 co-authored A Hinge of History: Governance in an Emerging New World on some key insights that emerged from the multiyear series of roundtables and expert contributions.

Early life, Marine Corps

George Pratt Shultz was born Dec. 13, 1920, in New York City and was raised in Englewood, New Jersey.

Shultz earned his bachelor’s degree from Princeton University in economics in 1942. After graduating, Shultz served in the Pacific theater as a member of the U.S. Marine Corps from 1942 to 1945, eventually becoming a captain. While stationed in Hawaii, Shultz met his first wife, Army nurse Helena “O’Bie” O’Brien, with whom he had five children. They were married for 49 years until her passing in 1995. He married Charlotte Mailliard, chief of protocol for the state of California, in 1997.

After his military service, Shultz continued his studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned a doctorate in industrial economics in 1949. Shultz taught at MIT from 1948 to 1957. In 1955, he took a leave of absence for a year and served as a senior staff economist on President Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers. Shultz moved to the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business in 1957, where he became dean in 1962 and served until 1968.

Scholar, statesman, business leader

Shultz began his association with Stanford in 1968 for a year fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS). However, his time at CASBS was cut short when Nixon asked him to join his Cabinet as secretary of labor in January 1969. In 1970, Shultz went on to become the first director of the newly formed Office of Management and Budget and then in 1972 was named secretary of the treasury, a position he held until 1974.

George Shultz (right) and his wife Charlotte (left) show Princess Mathilde of Belgium and Crown Prince Philippe of Belgium around the Stanford campus during their visit in 2003. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Shultz then accepted a part-time faculty position at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where he taught in the school’s Public Management Program – the first program of its kind to examine issues of public and nonprofit management and its relationship to the business sector.

During the Reagan administration, Shultz served as the chairman of the President’s Economic Policy Advisory Board (1981-82), in addition to his secretary of state position. After leaving government service in 1989, Shultz rejoined Stanford and the Bechtel Group in leadership posts.

Shultz’s resolve for nuclear nonproliferation drew him to the renowned Stanford physicist and arms control expert, the late Sidney Drell, who served as deputy director for SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory from 1969 to 1998 and was a senior fellow at Hoover. They forged a productive professional partnership, becoming close friends and co-authoring numerous books and papers on how to rid the world of nuclear weapons, including the 2014 publication with Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn, Nuclear Security: The Problems and the Road Ahead.

Energy, environment, students

Shultz was deeply committed to addressing climate change.

“Over the past four decades, the United States has been on an energy roller coaster that has landed us, unnecessarily, in a place that is dangerous to our economy, our national security and our climate,” Shultz said in a 2008 announcement for an initiative he launched at the Hoover Institution, the Shultz-Stephenson Task Force on Energy Policy.

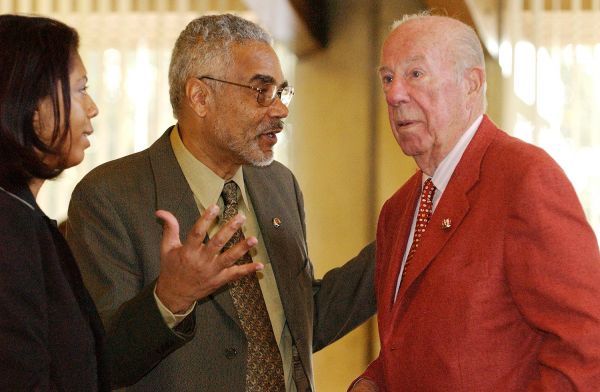

Hoover research fellow Kiron K. Skinner, left, and former Secretary of State George Shultz, right, are greeted by Professor Clayborne Carson at the event inaugurating the King Institute for Research and Education.

Shultz co-authored The State Clean Energy Cookbook – a collaboration between the Hoover Institution and the Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance – that provided states with guidance on energy-efficient initiatives. He also served as chair of the advisory board of Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy.

Devoted to student life and scholarship at Stanford, Shultz established numerous fellowships for students, including the George P. Shultz Fellowship in Canadian Studies, The George and Charlotte Shultz Fellowship for Modern Israel Studies and The Shultz Graduate Student Fellowship in Economic Policy.

Shultz was an advisory board member of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) since the institute’s creation in 1982. In celebration of Shultz’s 100th birthday, SIEPR created a faculty fellow position that recognizes his career in public service and contributions to economic policy.

At Hoover, two fellows are also named in his recognition: the George P. Shultz Senior Fellow in Economics, currently held by the Stanford economist John B. Taylor, and the George P. Shultz Senior Fellow in Foreign Policy and National Security Affairs, currently held by Abraham D. Sofaer, a former district judge and State Department legal advisor.

In addition, preparation is underway at the Lou Henry Hoover Building for the construction of the George Shultz Fellows Building, which will replace the existing structure. The new building will house Hoover fellows as well as a digital lab to serve students and scholars in new and modern ways – a lasting testimony to Shultz’s keen eye toward the future.

Shultz’s numerous honors include the Medal of Freedom (1989), the nation’s highest civilian honor, as well as many honorary degrees. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

In early December 2020, right before his centennial birthday, Shultz wrote an opinion piece for the Washington Post, titled “The 10 most important things I’ve learned about trust over my 100 years.” He wrote:

“Dec. 13 marks my turning 100 years young. I’ve learned much over that time, but looking back, I’m struck that there is one lesson I learned early and then relearned over and over: Trust is the coin of the realm. When trust was in the room, whatever room that was – the family room, the schoolroom, the locker room, the office room, the government room or the military room – good things happened. When trust was not in the room, good things did not happen. Everything else is details.”

Shultz is survived by his wife, Charlotte, and five children: Margaret Tilsworth, Kathleen Jorgensen, Peter Shultz, Barbara White and Alexander Shultz, as well as 11 grandchildren and 9 great-grandchildren.

Media Contacts

Jeff Marschner, Hoover Institution: jmarsch@stanford.edu