A study group of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAA&S) led by two Stanford physicists recently released a statement calling for global cooperation in the fight against COVID-19 and for the U.S. to take a leadership role in that effort.

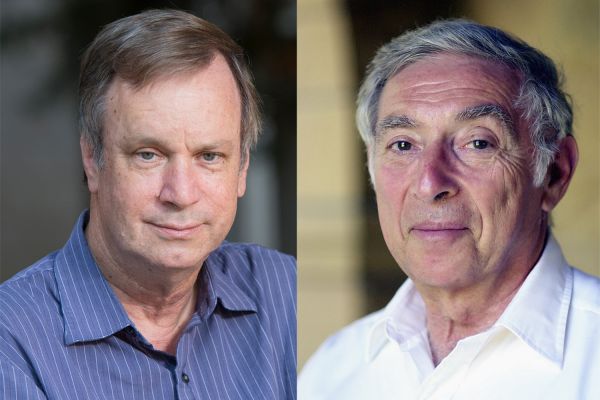

Since 2016, the “Challenges for International Scientific Partnerships” (CISP) project, led by Peter Michelson and Arthur Bienenstock, studies and articulates, particularly for audiences in the U.S., the benefits of international scientific collaboration across many disciplines. The group’s recent statement was prompted by the COVID-19 outbreak and its rapid global spread.

“Important lessons on disease management can be learned from around the world as each nation brings its expertise and experience to bear on addressing this crisis,” the statement reads. “In some countries, testing and case-tracking have been extensive. In others, previous experiences with other highly contagious diseases such as Ebola and SARS have informed their pandemic preparedness and response … Collaboration with both well-established and emerging international scientific partners alike is critical.”

Michelson, senior associate dean for the natural sciences and the Luke Blossom Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, and Bienenstock, professor emeritus of photon science, proposed that the AAA&S undertake a study of U.S. participation in large-scale scientific facilities several years ago.

“We perceived the future facilities in high energy physics and other fields would be too expensive and complex to be funded solely by, and located in, the U.S,” said Bienenstock.

The academy agreed and asked Bienenstock and Michelson to co-chair a broader project. “They saw that the scope of scientific challenges the world faces requires the participation of researchers across the globe and cooperation among them,” Michelson said.

The issues and challenges being examined by CISP range from shared scientific facilities to distributed networks of collaborators in a variety of disciplines. There are now two active working groups. The one Michelson and Bienenstock are a part of explores Large-Scale Science. The other one explores issues particular to U.S. scientific collaborations that are peer-to-peer with partners in other countries, particularly those with limited resources seeking to increase their scientific capacity.

Here, Michelson and Bienenstock discuss the current need for greater global scientific cooperation and the ways multi-national teams have and should continue to work together to fight COVID-19.

Why is the AAA&S calling for greater international scientific cooperation in this moment?

The recent statement was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the broad consensus among the study participants that this is a critical time to call for continued and additional collaboration between the U.S. and international scientific partners. While this statement is focused on COVID-19, it urges expanded and improved collaborations with scientific partners, particularly in low and middle-income countries to provide insight and expertise on scientific challenges that the U.S. faces.

What is the value of foundational and applied research that is global?

The value of science is not only to answer interesting questions about nature but also to advance knowledge that can lead to applications and that has implications for society at large. The world we live in is now globally connected, and this is driven by science and technology. We all need to understand the implications of these connections. No one country has a monopoly on scientific knowledge. Collaboration is a necessity if we are to remain knowledgeable and have expertise across a broad range of scientific disciplines. Indeed, this is reflected in scientific publications in leading journals for which the author lists are increasingly multinational.

What role did international cooperation and U.S. leadership play in efforts to fight past epidemics and pandemics?

We are both physicists and neither of us are experts about virology or pandemics. However, several members of our study group are experts in these areas and in public health. We have learned a number of lessons from them including that international cooperation is essential not only during a pandemic but also well before a crisis occurs. It is important for the U.S. to be engaged in partnerships. This is why the academy study statement states: “We urge the U.S. to act as a leader within the international scientific community in coordinating a global pandemic response, and we discourage nationalistic or competitive approaches that could threaten the efficacy of efforts to coordinate.” Our study group argues that international collaboration is essential for scientific advancements across disciplines and at all scales.

How is the international scientific community currently working together in the fight against COVID-19?

One can gain insight into the various ways that the global international scientific community is working together in the fight against COVID-19, by looking at recent publications in leading scientific journals such as The Lancet, Nature Medicine, and the New England Journal of Medicine.

For example, one of the first papers on the findings of contact tracing, involving the first 41 patients identified in Wuhan, China, was published by The Lancet on Jan. 24, 2020. We note that the publishers have provided free access to COVID-19 related research articles because of the importance of information sharing. The authorship of many of the papers is also international, with many authors from China, Europe and the U.S.

What do you think the general public often misunderstands about how contemporary science works?

The public often doesn’t fully appreciate how intensely collaborative modern research is or recognize that scientific explanations are not set in stone. They’re malleable, and are subject to change when new data are collected that provide more insight and explain a phenomenon or observation better. It is very healthy, and indeed essential, for scientists to challenge conclusions drawn by other scientists in a rigorous manner as part of the pursuit of knowledge. Science depends on peer review and feedback.

Related to the public perception of science, scientists doing fundamental research without a clear application are often asked about the value of their research – in other words, why their research is a public good. Abraham Flexner provided an eloquent answer to this question. In his 1939 essay “The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge,” he concluded that “throughout the whole history of science most of the really great discoveries which had ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind had been made by men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity.”

What types of policy recommendations and best practices for international cooperation does your Large-Scale Science Working Group hope to identify?

The report on large-scale science partnerships is in draft form, and we and the academy are still refining the recommendations and best practices. They will be based on an extensive set of conversations with various science funding agencies in the U.S. as well as abroad. We also have looked at lessons learned from a number of international projects in a variety of fields. The purpose of the recommendations, particularly for partnerships on large-scale facilities, will be aimed at making the U.S. a better international partner. We are convinced that these partnerships will be increasingly important for supporting U.S. science going forward and contributing to our knowledge base.

Media Contacts

Joy Leighton, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: joy.leighton@stanford.edu