Like the eponymous character in Shel Silverstein’s classic children’s tale, trees are generous with their gifts, cleaning the air we breathe and slowing the ravages of global warming by absorbing about a quarter of all human-caused carbon dioxide emissions. But this generosity likely can’t last forever in the face of unabated fossil fuel consumption and deforestation. Scientists have long wondered whether trees and plants could reach a breaking point and no longer adequately absorb carbon dioxide.

Trees such as these in Sequoia National Park will continue to absorb carbon dioxide at generous rates through at least the end of the century, a new study finds. (Image credit: Kolibrik/Pixabay)

An international team led by scientists at Stanford University and the Autonomous University of Barcelona finds reason to hope trees will continue to suck up carbon dioxide at generous rates through at least the end of the century. However, the study published Aug. 12 in Nature Climate Change warns that trees can only absorb a fraction of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and their ability to do so beyond 2100 is unclear.

“Keeping fossil fuels in the ground is the best way to limit further warming,” said study lead author César Terrer, a postdoctoral scholar in Earth system science in Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. “But stopping deforestation and preserving forests so they can grow more is our next-best solution.”

Weighing carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide – the dominant greenhouse gas warming the earth – is food for trees and plants. Combined with nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, it helps trees grow and thrive. But as carbon dioxide concentrations rise, trees will need extra nitrogen and phosphorus to balance their diet. The question of how much extra carbon dioxide trees can take up, given limitations of these other nutrients, is a critical uncertainty in predicting global warming.

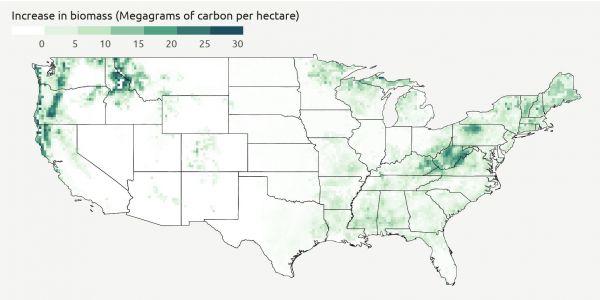

Potential increase in plant biomass in the U.S. for carbon dioxide levels expected in 2100. (Image credit: César Terrer)

“Planting or restoring trees is like putting money in the bank,” said co-author Rob Jackson, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor in Earth System Science at Stanford. “Extra growth from carbon dioxide is the interest we gain on our balance. We need to know how high the interest rate will be on our carbon investment.”

Several individual experiments, such as fumigating forests with elevated levels of carbon dioxide and growing plants in gas-filled chambers, have provided critical data but no definitive answer globally. To more accurately predict the capacity of trees and plants to sequester carbon dioxide in the future, the researchers synthesized data from all elevated carbon dioxide experiments conducted so far – in grassland, shrubland, cropland and forest systems – including ones the researchers directed.

Using statistical methods, machine-learning, models and satellite data, they quantified how much soil nutrients and climate factors limit the ability of plants and trees to absorb extra carbon dioxide. Based on global datasets of soil nutrients, they also mapped the potential of carbon dioxide to increase the amount and size of plants in the future, when atmospheric concentrations of the gas could double.

Their results show that carbon dioxide levels expected by the end of the century should increase plant biomass by 12 percent, enabling plants and trees to store more carbon dioxide – an amount equivalent to six years of current fossil fuel emissions. The study highlights important partnerships trees forge with soil microbes and fungi to help them take up the extra nitrogen and phosphorus they need to balance their additional carbon dioxide intake. It also emphasizes the critical role of tropical forests, such as those in the Amazon, Congo and Indonesia, as regions with the greatest potential to store additional carbon.

“We have already witnessed indiscriminate logging in pristine tropical forests, which are the largest reservoirs of biomass in the planet,” said Terrer, who also has a secondary affiliation with the Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. “We stand to lose a tremendously important tool to limit global warming.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

This paper is a contribution to the Global Carbon Project, which Jackson chairs. Jackson is also senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Precourt Institute for Energy. Co-authors also include Chris Field, the Perry L. McCarty Director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the Melvin and Joan Lane Professor for Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies, professor of Earth system science and of biology and senior fellow at the Precourt Institute for Energy; and researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems, Imperial College London, Macquarie University, Tsinghua University, University of California at Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of Vienna, University of Antwerp, California Institute of Technology, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Minnesota, Western Sydney University, the Ecological and Forestry Applications Research Centre, Northern Arizona University, Leiden University, James Cook University, University of Idaho, Peking University, Chinese Academy of Sciences, AgResearch, University of Tasmania, United States Department of Agriculture, University of New South Wales, Justus Liebig University of Giessen, University College Dublin, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Maastricht University, Utrecht University, Wageningen University, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology and Hokkaido University.

The research was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (U.K.), the Spanish Ministry of Science, the European Research Council, the Fund for Scientific Research – Flanders (Belgium),the U.S. Department of Energy, NASA, the California Institute of Technology and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Media Contacts

César Terrer, Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences; Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: cesar.terrer@me.com

Rob Jackson, School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences: (650) 497-5841, rob.jackson@stanford.edu, jacksonlab.stanford.edu

Rob Jordan, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment: (650) 721-1881, rjordan@stanford.edu