Walk into Shamit Kachru’s office, and the first things you’ll notice are the couch and the coffee table that sits in front of it, both situated across from a chalkboard that takes up most of one wall. Intentionally or not, it is a social space. Kachru is a professor of physics and director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics, and what that means in practical terms is that when he’s not reading books or printouts of academic papers, he’s usually talking to other people and sharing ideas.

Of late, Kachru’s ideas include thoughts on how to better understand black holes through the lens of number theory, a branch of pure mathematics concerned with questions such as “What is the distribution of prime numbers?” And as a new member of Stanford Bio-X, more and more of the ideas Kachru thinks about concern biology and the theory of evolution, a field Kachru got into simply by talking to a fellow physicist.

Here, in a glimpse into the lives of theoretical physicists, Kachru, his former graduate student Natalie Paquette and two current graduate students, Brandon Rayhaun and Richard Nally, talk about what it’s like to be a theoretical physicist today – how they got into the field, what keeps them motivated and what their work means to them.

Shamit Kachru

Kachru has been studying physics in one form or another for three decades. He spoke about his newfound interest in theoretical biology, why he likes being an administrator and what motivates him to continue on in science.

“We’re not all marveling at the universe all the time. But occasionally in my work, and these are the moments that keep one going, you do encounter something that really inspires awe in a serious way.”

Natalie Paquette

Paquette graduated from Stanford in 2017 and is now a Sherman Fairchild Postdoctoral Fellow at Caltech. She talked about discovering physics in college, why physics never gets old and how, in a way, she has a superpower.

“String theory feels like a little superpower that I have, this physical intuition that enables me to make connections and have insights into things that by rights I should not be able to say anything interesting about.”

Brandon Rayhaun

Rayhaun is a third-year graduate student and works on string theory with Kachru. He spoke about what science means to him, how no day is particularly typical and the other Stanford professor who inspired him to pursue a career in physics.

“It was 5 a.m. and I had watched maybe four or five hours of Lenny Susskind lectures and I forgot to study for the French exam. That’s when I got more interested in actually pursuing physics as a possibility.”

Richard Nally

Nally is a fourth-year graduate student in Kachru’s group studying black holes and number theory. He spoke about the experiences that led him to physics, the excitement of seeing math come alive and the inherently social nature of his work.

“One of the things I like so much about this field is that it’s very social. People tend to be confused about a lot of the same things, so you go talk to somebody else and find out their perspective on it.”

Shamit Kachru

Shamit Kachru, Professor of Physics and Director, Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Shamit Kachru’s work is abstract and mathematical, and as a result, his days are spent reading academic journals, working out his thoughts on a pad of paper or a chalkboard and sharing ideas with other physicists. In the big picture, he is on a kind of search for Platonic forms – eternal, unchangeable truths that exist outside of our experience of them. Kachru talks about why he likes administrative positions (it’s not the paperwork), why he recently decided to branch out into theoretical biology and the sense of awe that keeps him going.

“Right now I’m department chair, and I’m also director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics, and so you might look at this and say, ‘OK, this is somebody who is going to turn 50 soon and has decided to be an administrator.’ And this is a total misreading. The thing that interested me about both of those roles is they give you the ability and even force you to interact with even more people who tell you more interesting things that you otherwise wouldn’t hear.

“I personally get a lot of joy out of interacting with students. I’ve had graduate students who were wonderful and who play, as I get older, a really important role in my research. I’ve just started taking biology students. It’s a different cohort. They’ll teach me different things. A lot of research is two different people explaining things to each other, then you put those two things together and at that moment you get something new.

“I have spent some time in the past couple of years hanging out in the group meetings of Dmitri Petrov’s group and Daniel Fisher’s group in biology and Bio-X, and have heard absolutely fascinating things there about evolutionary experiment and theory. I finally decided that the time was right for me to start trying to contribute my own research to ongoing attempts to understand evolutionary dynamics.

“Biology was the place I entered science as a kid. I used to get these cards from the World Wildlife Federation with pictures of pandas and belugas and raccoons – you know, whatever they put on these cards. And so you grow up already with a natural affinity for living things. Only much later when I was on leave from Stanford at the University of California, Santa Barbara, did I meet a prominent physicist, Boris Shraiman, who transitioned to studying theoretical questions in biology. Without any preconception, I spent a lot of my time there listening to the things he works on and going to a workshop. What struck me was what an exciting time it was in their field. What’s happened is people started to do experiments in evolution, and this together with the ability to rapidly sequence genomes opens up a host of questions to scientific inquiry.

“Now if you ask, ‘What are motivations to understand how evolution works?’ here I can be practical. The 1918 flu killed millions and millions of people, and sometime there will be another such flu strain and millions and millions of people will die. If you ask, ‘How are we going to combat the flu,’ some of the best ideas involve studying the way that different flu strains’ genetic lines of descent are splitting and branching, to figure out which flu is the most successful, to figure out what the vaccine should be that we use to combat what next year’s flu is likely to be. And that work came out of theoretical physicists working with biologists.

“I’m not a religious person, but when you read accounts of religious people about how they feel, there is a feeling of awe people can have. Now, daily life as a scientist, just like daily life as anything, is mostly, you know, you get up and you’re tired and you have to feed the rabbits or whatever you happen to have, and so on and so forth. So we’re not all marveling at the universe all the time. But occasionally in my work, and these are the moments that keep one going, you do encounter something that really inspires awe in a serious way.

“For many people, the way it comes about is some fact about nature that’s discovered in an experiment, and that can happen for me too. But as a theorist, another way it really comes about is when some fact about nature, or at least a toy model of something that could be seen in nature, turns out to also have a really deep and fundamental origin in pure mathematics, which as far as I can tell is the closest thing to pure Platonic thought that we have as humans.”

Shamit Kachru

Shamit Kachru, Professor of Physics and Director, Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Shamit Kachru’s work is abstract and mathematical, and as a result, his days are spent reading academic journals, working out his thoughts on a pad of paper or a chalkboard and sharing ideas with other physicists. In the big picture, he is on a kind of search for Platonic forms – eternal, unchangeable truths that exist outside of our experience of them. Kachru talks about why he likes administrative positions (it’s not the paperwork), why he recently decided to branch out into theoretical biology and the sense of awe that keeps him going.

“Right now I’m department chair, and I’m also director of the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics, and so you might look at this and say, ‘OK, this is somebody who is going to turn 50 soon and has decided to be an administrator.’ And this is a total misreading. The thing that interested me about both of those roles is they give you the ability and even force you to interact with even more people who tell you more interesting things that you otherwise wouldn’t hear.

“I personally get a lot of joy out of interacting with students. I’ve had graduate students who were wonderful and who play, as I get older, a really important role in my research. I’ve just started taking biology students. It’s a different cohort. They’ll teach me different things. A lot of research is two different people explaining things to each other, then you put those two things together and at that moment you get something new.

“I have spent some time in the past couple of years hanging out in the group meetings of Dmitri Petrov’s group and Daniel Fisher’s group in biology and Bio-X, and have heard absolutely fascinating things there about evolutionary experiment and theory. I finally decided that the time was right for me to start trying to contribute my own research to ongoing attempts to understand evolutionary dynamics.

“Biology was the place I entered science as a kid. I used to get these cards from the World Wildlife Federation with pictures of pandas and belugas and raccoons – you know, whatever they put on these cards. And so you grow up already with a natural affinity for living things. Only much later when I was on leave from Stanford at the University of California, Santa Barbara, did I meet a prominent physicist, Boris Shraiman, who transitioned to studying theoretical questions in biology. Without any preconception, I spent a lot of my time there listening to the things he works on and going to a workshop. What struck me was what an exciting time it was in their field. What’s happened is people started to do experiments in evolution, and this together with the ability to rapidly sequence genomes opens up a host of questions to scientific inquiry.

“Now if you ask, ‘What are motivations to understand how evolution works?’ here I can be practical. The 1918 flu killed millions and millions of people, and sometime there will be another such flu strain and millions and millions of people will die. If you ask, ‘How are we going to combat the flu,’ some of the best ideas involve studying the way that different flu strains’ genetic lines of descent are splitting and branching, to figure out which flu is the most successful, to figure out what the vaccine should be that we use to combat what next year’s flu is likely to be. And that work came out of theoretical physicists working with biologists.

“I’m not a religious person, but when you read accounts of religious people about how they feel, there is a feeling of awe people can have. Now, daily life as a scientist, just like daily life as anything, is mostly, you know, you get up and you’re tired and you have to feed the rabbits or whatever you happen to have, and so on and so forth. So we’re not all marveling at the universe all the time. But occasionally in my work, and these are the moments that keep one going, you do encounter something that really inspires awe in a serious way.

“For many people, the way it comes about is some fact about nature that’s discovered in an experiment, and that can happen for me too. But as a theorist, another way it really comes about is when some fact about nature, or at least a toy model of something that could be seen in nature, turns out to also have a really deep and fundamental origin in pure mathematics, which as far as I can tell is the closest thing to pure Platonic thought that we have as humans.”

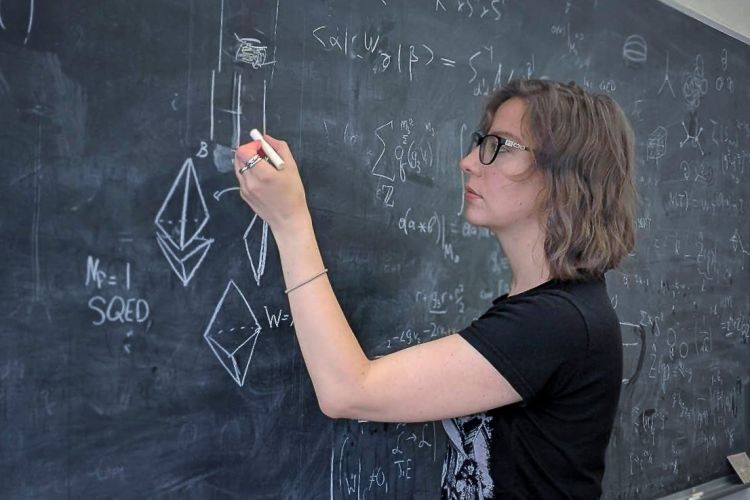

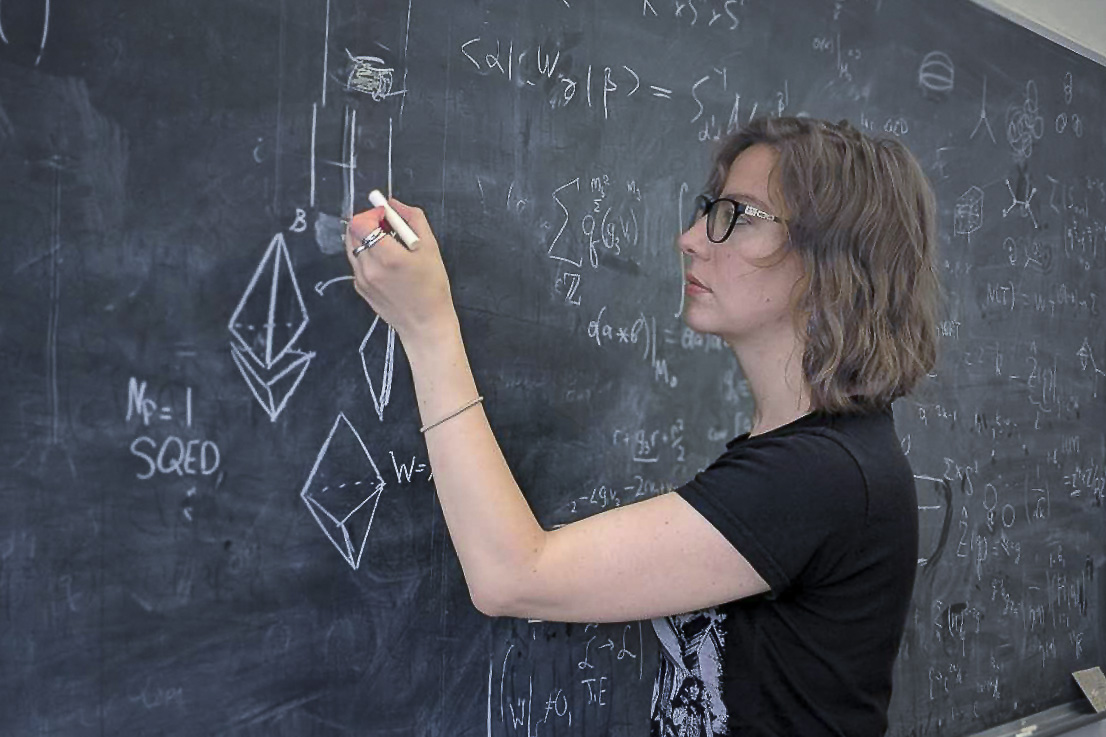

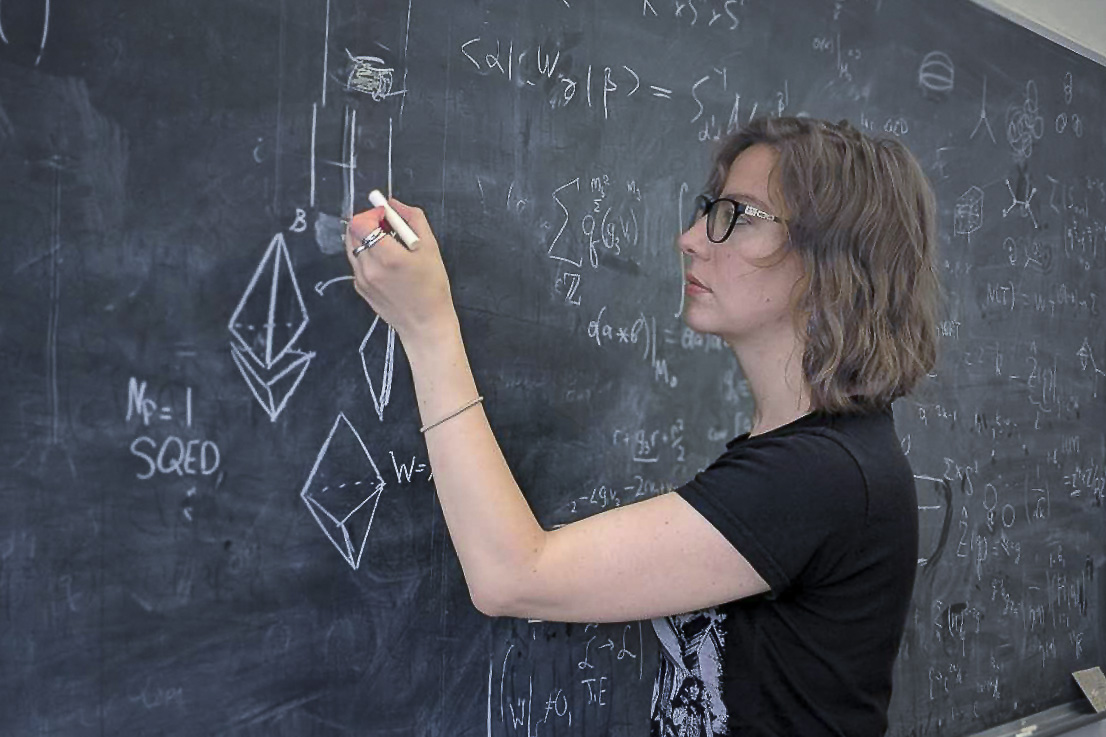

Natalie Paquette

Physicist Natalie Paquette (Image credit: Ying-Hsuan Lin)

Natalie Paquette works on the mathematics underlying string theory and quantum field theory. Until 2017, she was a graduate student in Kachru’s group. She is now a Sherman Fairchild Postdoctoral Fellow at Caltech. Here, she talks about how she first fell in love with physics in college, why string theory is a kind of mathematical superpower and why, for her, physics never gets boring.

“I didn’t really know that I wanted to do physics until I was in college. I remember when I was young I liked to read and write a lot. I thought about being an author. I briefly contemplated being a doctor. I thought about being an engineer, a marine biologist – I really wasn’t sure. I was interested in all sorts of things, and so it wasn’t really until I came to college that I got a better sense of who I was interest-wise and what my academic aptitudes were. I went to Cornell University as an undergrad, and originally I matriculated in biological engineering, and then eventually I ended up taking a physics class. I just knew after that class that physics was the thing that I liked the best.

“String theory feels like a little superpower that I have, this physical intuition, this extremely powerful framework that enables me to make connections and have insights into things that by rights I should not be able to say anything interesting about. I’m not trained as a geometer, I’m not trained as a number theorist, but somehow by thinking really hard about aspects of string theory, I’m able to get insight into all of these far-reaching mathematical fields. I find that sort of really amazing and powerful. Of course, compared to mathematicians in any of these areas, I’m still a dilettante, but hopefully an insightful one. It’s just been really fun for me to learn mathematics through this unconventional physical lens.

“Does physics ever get boring? No, it never gets boring. If I’m really frustrated by the particular things I’m working on or if I feel really stuck, I’ll try to learn some subject in condensed matter physics or I’ll try to learn something in cosmology or just some other area of physics, and that’s all it takes for me to be re-inspired with this subject. I need to take breaks from time to time and study other things and think about other things, but the subject as a whole definitely never gets boring for me.

“I am a lot more regimented now than I was when I was a grad student. I wasn’t a morning person. I was one of those sleep-late-and-work-late, very night-shifted grad students. Right now I’m trying to wake up around 7 or 7:30. I made a choice to start training in mixed martial arts recently, and I do my training in the morning and that forced me to rotate my whole schedule. There is something about doing really, really intense physical activity that sort of balances how intense your day can be mentally.

“I don’t think physics is the only interesting thing in the world. That would be very shortsighted of me. I do have other things I’m interested in, things I learned about as a hobby, things related to economics or biology or other things. There’s all kinds of cool stuff going on in all kinds of other places. And so if nothing worked out with physics, then I’m sure I could find something else interesting to do and be happy about it. But as long as I have a chance of getting to do my favorite thing indefinitely, if I’m lucky enough to get a tenure-track job, then I’ll try to do that as long as I can.”

Natalie Paquette

Physicist Natalie Paquette (Image credit: Ying-Hsuan Lin)

Natalie Paquette works on the mathematics underlying string theory and quantum field theory. Until 2017, she was a graduate student in Kachru’s group. She is now a Sherman Fairchild Postdoctoral Fellow at Caltech. Here, she talks about how she first fell in love with physics in college, why string theory is a kind of mathematical superpower and why, for her, physics never gets boring.

“I didn’t really know that I wanted to do physics until I was in college. I remember when I was young I liked to read and write a lot. I thought about being an author. I briefly contemplated being a doctor. I thought about being an engineer, a marine biologist – I really wasn’t sure. I was interested in all sorts of things, and so it wasn’t really until I came to college that I got a better sense of who I was interest-wise and what my academic aptitudes were. I went to Cornell University as an undergrad, and originally I matriculated in biological engineering, and then eventually I ended up taking a physics class. I just knew after that class that physics was the thing that I liked the best.

“String theory feels like a little superpower that I have, this physical intuition, this extremely powerful framework that enables me to make connections and have insights into things that by rights I should not be able to say anything interesting about. I’m not trained as a geometer, I’m not trained as a number theorist, but somehow by thinking really hard about aspects of string theory, I’m able to get insight into all of these far-reaching mathematical fields. I find that sort of really amazing and powerful. Of course, compared to mathematicians in any of these areas, I’m still a dilettante, but hopefully an insightful one. It’s just been really fun for me to learn mathematics through this unconventional physical lens.

“Does physics ever get boring? No, it never gets boring. If I’m really frustrated by the particular things I’m working on or if I feel really stuck, I’ll try to learn some subject in condensed matter physics or I’ll try to learn something in cosmology or just some other area of physics, and that’s all it takes for me to be re-inspired with this subject. I need to take breaks from time to time and study other things and think about other things, but the subject as a whole definitely never gets boring for me.

“I am a lot more regimented now than I was when I was a grad student. I wasn’t a morning person. I was one of those sleep-late-and-work-late, very night-shifted grad students. Right now I’m trying to wake up around 7 or 7:30. I made a choice to start training in mixed martial arts recently, and I do my training in the morning and that forced me to rotate my whole schedule. There is something about doing really, really intense physical activity that sort of balances how intense your day can be mentally.

“I don’t think physics is the only interesting thing in the world. That would be very shortsighted of me. I do have other things I’m interested in, things I learned about as a hobby, things related to economics or biology or other things. There’s all kinds of cool stuff going on in all kinds of other places. And so if nothing worked out with physics, then I’m sure I could find something else interesting to do and be happy about it. But as long as I have a chance of getting to do my favorite thing indefinitely, if I’m lucky enough to get a tenure-track job, then I’ll try to do that as long as I can.”

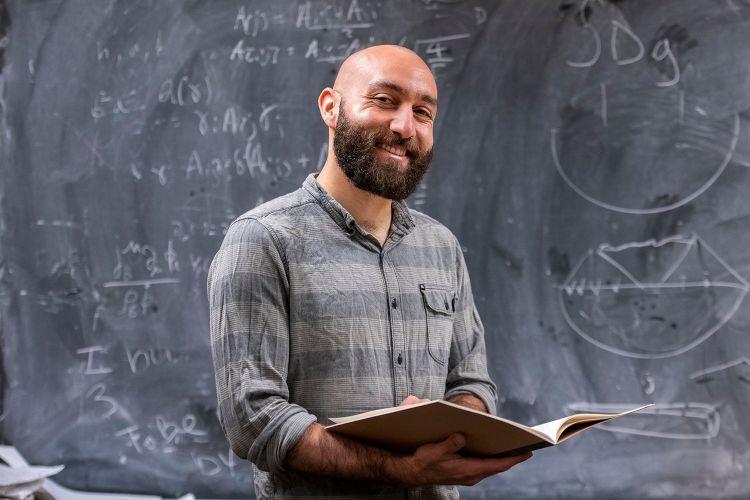

Brandon Rayhaun

Physics graduate student Brandon Rayhaun (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Graduate student Brandon Rayhaun works with Kachru probing the mathematical connections between string theory, black holes and number theory. Of his choice to pursue a career in physics, he says “it was sort of serendipitous.” Here, he talks about the late-night epiphany that solidified his desire to pursue physics, a typical day in the life of a theoretical physics graduate student and why it’s worth developing theories that, for the time being at least, can’t be tested.

“I had various romantic notions about theoretical physics because I grew up watching various documentaries about string theory. But I think if I had to pinpoint the exact moment where I really knew that I wanted to study physics, I was in high school studying for a French exam, and I was procrastinating, looking up random videos on YouTube, and I stumbled upon Leonard Susskind’s quantum mechanics lectures. It was 5 a.m. and I had watched maybe four or five hours of Lenny Susskind lectures and I forgot to study for the French exam. That’s when I got more interested in actually pursuing physics as a possibility.

“No day’s terribly typical. I wake up anytime between 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. It’s truly that variable. Part of that is because there are times where I’m in a place where I can be working and there are other times where I’m just not feeling it. I’ve learned over time to not force myself to do creative type work when I’m not in the zone or I’m not feeling it. But when I’m really feeling it, I’ll be too excited to stay asleep for too long, so I’ll force myself to wake up at 6 a.m. or 5 a.m. or whatever and get up, and I’m really eager and excited to think about the problem I was thinking about the night before.

“Why should we do it? This is a question I still grapple with. The fact is that the theories we’re working with offer predictions that are currently inaccessible to experiments. I think there is this amnesia about things. We look at things like quantum mechanics, and in retrospect it’s clear that we should have done it because it led to all kinds of interesting technological advancements, like MRI machines, your computer, everything uses quantum mechanics. But at the time that people were thinking about it, when it first arrived on the scene, it was an incredibly abstract, really removed thing.

“Here’s another way to answer the question. I mean, why do we do art? You can make sort of similar arguments that art doesn’t impact humans in the same way that antibiotics do or something like that. But I would argue that it really does. Art adds beauty to our lives.

“I tend to think about string theory in a similar way. Science is a collection of stories, really beautiful stories, about how the universe works. We need to do a better job of communicating these stories to people, but say we were communicating these stories to people – that I think would be a totally worthwhile endeavor. I think scientists would then be like a combination of artists and adventurers. There are these adventurers who go out into these abstract universes, kind of find patterns, interesting gems, interesting rocks and bring them back and then show them to people and add some beauty to their lives.”

Brandon Rayhaun

Physics graduate student Brandon Rayhaun (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Graduate student Brandon Rayhaun works with Kachru probing the mathematical connections between string theory, black holes and number theory. Of his choice to pursue a career in physics, he says “it was sort of serendipitous.” Here, he talks about the late-night epiphany that solidified his desire to pursue physics, a typical day in the life of a theoretical physics graduate student and why it’s worth developing theories that, for the time being at least, can’t be tested.

“I had various romantic notions about theoretical physics because I grew up watching various documentaries about string theory. But I think if I had to pinpoint the exact moment where I really knew that I wanted to study physics, I was in high school studying for a French exam, and I was procrastinating, looking up random videos on YouTube, and I stumbled upon Leonard Susskind’s quantum mechanics lectures. It was 5 a.m. and I had watched maybe four or five hours of Lenny Susskind lectures and I forgot to study for the French exam. That’s when I got more interested in actually pursuing physics as a possibility.

“No day’s terribly typical. I wake up anytime between 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. It’s truly that variable. Part of that is because there are times where I’m in a place where I can be working and there are other times where I’m just not feeling it. I’ve learned over time to not force myself to do creative type work when I’m not in the zone or I’m not feeling it. But when I’m really feeling it, I’ll be too excited to stay asleep for too long, so I’ll force myself to wake up at 6 a.m. or 5 a.m. or whatever and get up, and I’m really eager and excited to think about the problem I was thinking about the night before.

“Why should we do it? This is a question I still grapple with. The fact is that the theories we’re working with offer predictions that are currently inaccessible to experiments. I think there is this amnesia about things. We look at things like quantum mechanics, and in retrospect it’s clear that we should have done it because it led to all kinds of interesting technological advancements, like MRI machines, your computer, everything uses quantum mechanics. But at the time that people were thinking about it, when it first arrived on the scene, it was an incredibly abstract, really removed thing.

“Here’s another way to answer the question. I mean, why do we do art? You can make sort of similar arguments that art doesn’t impact humans in the same way that antibiotics do or something like that. But I would argue that it really does. Art adds beauty to our lives.

“I tend to think about string theory in a similar way. Science is a collection of stories, really beautiful stories, about how the universe works. We need to do a better job of communicating these stories to people, but say we were communicating these stories to people – that I think would be a totally worthwhile endeavor. I think scientists would then be like a combination of artists and adventurers. There are these adventurers who go out into these abstract universes, kind of find patterns, interesting gems, interesting rocks and bring them back and then show them to people and add some beauty to their lives.”

Richard Nally

Physics graduate student Richard Nally (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Graduate student Richard Nally is unabashed about his reasons for studying an abstract corner of theoretical physics, and it has nothing to do with the possibility his work might someday have practical value. Instead, he studies theoretical physics “because it’s cool.” Like many physicists, his interest in the subject grew from reading popular books written by leaders in the field, but Nally also cites a curiosity that grew out of a childhood conundrum.

“I was very clumsy. I dropped basically everything I got my hands on, and I could never quite understand why that happened. And so I asked. I wanted to understand why things fall basically. That’s still more or less what I think about.

“So I kept on asking my science teachers, and they all just said it’s this thing called gravity. So I kept on asking and asking and heckling, and eventually sometime in middle school one of them threw at me a copy of Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. I read it and I’m like, ‘OK, this is the coolest thing ever. I need to do this.’

“The big problem in theoretical physics very broadly is, there’s four forces in the universe, and one of them is very different than the others, and that one is gravity, and so we’re trying to understand how it works. There’s a framework for trying to understand it, string theory, and so that’s always what I wanted to work on.

“There are a couple different archetypical days. One is I lock myself in my office and read papers until I get confused, and then I go talk to someone about them. Another is you go to a seminar. Sometimes it’s on a topic very close to you and you understand it quite well. Sometimes it’s on a topic completely orthogonal to your research and you get confused very quickly. But you want to get the big picture and come up with an interesting question to ask.

“The third type of day is when you’re trying to find a good question to ask. You could ask, ‘Where did the universe come from?’ And that’s a question that people have been trying to answer forever, but that’s a problem that takes an infinite amount of work. You need to find a question that’s concrete enough that you can handle, interesting enough to keep on motivating yourself to do it and important enough that somebody else will care. That’s a struggle, and that’s sort of why you go to all of these seminars and read so many papers, just to understand what other people have been thinking about and do you have something to say.

“One of the things I like so much about this field is that it’s very social. People tend to be confused about a lot of the same things, or sometimes you find something very confusing that nobody else does, so you go talk to somebody else and find out their perspective on it. If you don’t talk to people, you’re never really going to understand all of what’s going on. Really, you’re always confused about something. That’s the natural state of doing research, and for me, a lot of the time being confused is part of the fun.

“The fun parts aren’t necessarily doing long calculations with twos and minus signs and all that other stuff that you’re going to screw up a million times, and you have to keep on redoing until you get it completely right and then you check and double-check and triple-check. I don’t think many people find that very exciting. What really excites me is when you can see the math come alive and give you some sort of picture of the reality that lives behind it.

“I want to continue in academia. It’s hard, you know. There are not enough jobs to go around. And it becomes very competitive very quickly. But I love it. I really can’t imagine doing anything else at this point in my life. For me what matters is being passionate about what I do every day, and that means doing physics.”

Richard Nally

Physics graduate student Richard Nally (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Graduate student Richard Nally is unabashed about his reasons for studying an abstract corner of theoretical physics, and it has nothing to do with the possibility his work might someday have practical value. Instead, he studies theoretical physics “because it’s cool.” Like many physicists, his interest in the subject grew from reading popular books written by leaders in the field, but Nally also cites a curiosity that grew out of a childhood conundrum.

“I was very clumsy. I dropped basically everything I got my hands on, and I could never quite understand why that happened. And so I asked. I wanted to understand why things fall basically. That’s still more or less what I think about.

“So I kept on asking my science teachers, and they all just said it’s this thing called gravity. So I kept on asking and asking and heckling, and eventually sometime in middle school one of them threw at me a copy of Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. I read it and I’m like, ‘OK, this is the coolest thing ever. I need to do this.’

“The big problem in theoretical physics very broadly is, there’s four forces in the universe, and one of them is very different than the others, and that one is gravity, and so we’re trying to understand how it works. There’s a framework for trying to understand it, string theory, and so that’s always what I wanted to work on.

“There are a couple different archetypical days. One is I lock myself in my office and read papers until I get confused, and then I go talk to someone about them. Another is you go to a seminar. Sometimes it’s on a topic very close to you and you understand it quite well. Sometimes it’s on a topic completely orthogonal to your research and you get confused very quickly. But you want to get the big picture and come up with an interesting question to ask.

“The third type of day is when you’re trying to find a good question to ask. You could ask, ‘Where did the universe come from?’ And that’s a question that people have been trying to answer forever, but that’s a problem that takes an infinite amount of work. You need to find a question that’s concrete enough that you can handle, interesting enough to keep on motivating yourself to do it and important enough that somebody else will care. That’s a struggle, and that’s sort of why you go to all of these seminars and read so many papers, just to understand what other people have been thinking about and do you have something to say.

“One of the things I like so much about this field is that it’s very social. People tend to be confused about a lot of the same things, or sometimes you find something very confusing that nobody else does, so you go talk to somebody else and find out their perspective on it. If you don’t talk to people, you’re never really going to understand all of what’s going on. Really, you’re always confused about something. That’s the natural state of doing research, and for me, a lot of the time being confused is part of the fun.

“The fun parts aren’t necessarily doing long calculations with twos and minus signs and all that other stuff that you’re going to screw up a million times, and you have to keep on redoing until you get it completely right and then you check and double-check and triple-check. I don’t think many people find that very exciting. What really excites me is when you can see the math come alive and give you some sort of picture of the reality that lives behind it.

“I want to continue in academia. It’s hard, you know. There are not enough jobs to go around. And it becomes very competitive very quickly. But I love it. I really can’t imagine doing anything else at this point in my life. For me what matters is being passionate about what I do every day, and that means doing physics.”