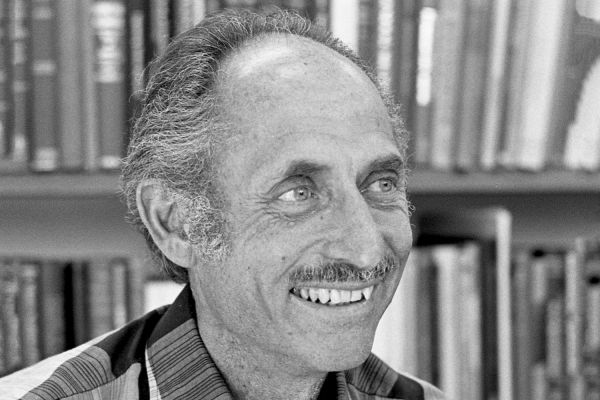

Thomas Reif Kane, a professor emeritus of applied mechanics and mechanical engineering at Stanford University, was a pioneer in the field of spacecraft dynamics, biomechanics and modern computational dynamics. Kind, intrepid and meticulously inquisitive, he was a beloved teacher and held visiting scholar positions around the world. Kane died at Stanford on Feb. 16 at the age of 94.

Thomas R. Kane, 1924-2019 (Image credit: Chuck Painter)

“Professor Kane wanted to understand the world around him as best as he could,” said Paul Mitiguy, an adjunct professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford and Kane’s former PhD student. “It was so fascinating to watch him and work with him. You touched greatness when you were with him.”

The field of dynamics involves trying to describe and predict the behavior of physical systems with many moving parts – such as a spacecraft with a robotic arm or an artificial limb – through mathematical equations. Early in his career, Kane concluded that traditional approaches to writing these equations relied too much on vague concepts. So, he developed an alternative that colleagues said was much more efficient and logical, now called Kane’s Method. He began teaching Kane’s Method in 1955 and it lives on in software for vehicles, spacecraft, robotics, biomechanics and many other mechanical and aerospace technologies.

“With the death of Professor Kane, the world of dynamics has lost its brightest star,” said Arun Banerjee, a consulting scientist at space technology company SSL, who co-authored eight papers with Kane. “He is gone, but to dynamicists the world over, his method of formulating equations of motion will remain as the best method to do dynamics.”

War photographer to Stanford professor

Kane was born March 23, 1924, in Vienna, Austria. He immigrated to the United States with his parents in 1938, after the fall of Austria to the Nazis. In 1943, Kane enlisted in the U.S. Army and was stationed in the South Pacific as a combat photographer. In a photograph of the official Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri, taken by Larry Keighley for the Saturday Evening Post, you can see Kane kneeling in the background with camera in hand.

Supported by the G.I. Bill, Kane went to Columbia University from 1946 to 1953, earning two BS degrees (in mathematics and civil engineering), an MS in civil engineering and a PhD in applied mechanics. After working as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Kane came to Stanford in 1961 as a professor of applied mechanics.

Swivel-hipped kitty made from a tennis ball, tape and wire by Professor Thomas Kane demonstrates how cats always manage to land on their feet. (Image credit: Chuck Painter)

“I believe that when my father began his life and work at Stanford, he knew he had arrived, that he was home,” said Linda Kane, his daughter. “It wasn’t just the climate or the open space, the beauty of the landscape – all of which he fully embraced, and which had initially drawn him to the area – rather it was the palpable sense of freedom, of possibility, that energized him and informed everything he was able to create and accomplish.”

Kane contributed to theory and techniques that helped astronauts control their orientation in space without exhausting themselves or requiring assistive devices. Part of this research, featured in Life magazine, involved studying the free-falling motion of cats and enlisting a trampolinist to practice in-air movements in a spacesuit. On one occasion, Kane acted as his own demonstration, twisting just-so atop a frictionless table to spin it 180-degrees. His about-face convinced officials from NASA of his ability to explain these complex movements with math.

During his academic career, Kane co-authored 10 textbooks and over 170 technical articles. He was a fellow of the American Astronautical Society and an Honorary Member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). When he won the American Astronautical Society’s Dirk Brouwer Award in 1983, the nomination stated, “If you asked any recognized group of experts in the area of space flight mechanics to pick the 10 best people in their field, Professor Kane’s name would undoubtedly appear on every list.” Kane was also the inaugural recipient in 2005 of the ASME D’Alembert Award, recognizing lifetime achievement and contribution to the field of multibody systems dynamics.

A kind teacher with high expectations

Kane came up with Kane’s Method for developing equations of motion because he could not find a person or book that explained existing methods to his satisfaction. Whether he was conducting research, writing or teaching, Kane was committed to having a detailed, precise understanding of his world – and he instilled that commitment in his students and collaborators.

“As soon as I took a course from him, I said, ‘That’s it. That’s the way a course should be taught,’” said David Levinson, a principal engineer in dynamics at SSL and Kane’s former graduate student. “Everything he said was so clear, and that was no accident. He analyzed the science of teaching and was then able to teach others, including me, how to teach.”

In addition to his time at Stanford, Kane taught in England, Brazil and China in temporary positions and spent three months in the Soviet Union in 1968 as part of an exchange program between the Russian and American academies of science. He also volunteered as a math tutor for high school students in Palo Alto and East Palo Alto and took great joy in being recognized by former students in the community.

“Whether you were old or young, as soon as he met you, Professor Kane had a way to connect with you,” said Mitiguy. “You got a sense of how much love he had for all the people around him. He was a beautiful man, on so many levels.”

Kane is survived by his wife, Ann Kane (née Andrews); his daughter, Linda; and his granddaughter, Elisabeth. His son, Jeffrey Kane, predeceased him in 2014. There will be no funeral or remembrance services, per Thomas Kane’s wishes.

Media Contacts

Taylor Kubota, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-7707; tkubota@stanford.edu