Science and art are often regarded as distinct – either a person can’t be serious about both or an interest in one must relate somehow to work in the other. In reality, many scientists participate in and produce art at all levels and in every medium.

Here are just a few of these people – students and faculty – who study the sciences at Stanford University but also take part in the arts, both professionally and casually. From first-time dancers to life-long painters, these scientists give us a glimpse into the many ways science and art intersect.

Image credit: Alice Lay

Image credit: Alice Lay

Image credit: Alice Lay

Image credit: Alice Lay

Image credit: Alice Lay

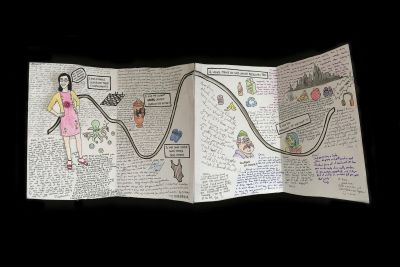

Image credit: Susan McConnell

Image credit: Susan McConnell

Image credit: Susan McConnell

Image credit: Susan McConnell

Image credit: Susan McConnell

Image credit: Susan McConnell

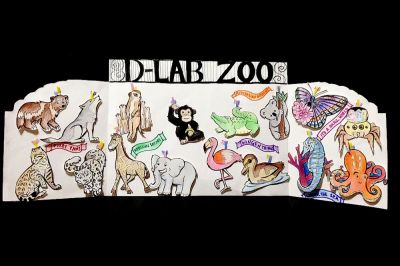

Image credit: Riley Suhar

Image credit: Riley Suhar

Image credit: Riley Suhar

Image credit: Riley Suhar

Image credit: Riley Suhar

Image credit: Riley Suhar