Less than 80 years after roughly 6,000 gay men perished in Nazi concentration camps, Germany has become one of the countries mostly widely accepting of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. Its capital of Berlin is known globally for its vibrant, diverse gay culture.

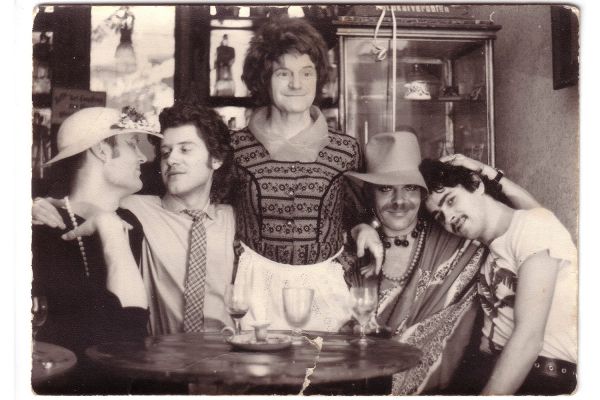

Several of East Germany’s gay activists, including well-known transgender woman Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, center, pose for a photo in the 1970s. (Image credit: Courtesy of Private Archives of Peter Rausch)

That stark cultural and political change intrigued Stanford researcher Samuel Clowes Huneke, a doctoral candidate in history, who began investigating how East and West Germany dealt with homosexuality from 1945 to 1990.

“I started this work with one big question: How does a country go from the Nazi dictatorship to becoming the standard bearer of gay rights that it is today?” said Huneke, who pursued the research as part of his doctoral dissertation. “And that explanation is not an obvious one.”

Huneke found that during the Cold War era, communist East Germany had more lenient sodomy laws and accepted gay activists’ demands more quickly than its democratic twin. As a result, East Germany contributed significantly to Germany’s pro-gay turn once the country unified in 1990, in some regards more than West Germany did.

“There is an assumption that the state of gay rights in Germany today is something that’s mostly due to events in democratic West Germany, which had a more vibrant gay culture and a more visible gay rights movement during the 1970s,” Huneke said. “But it actually had a lot to do with what was happening in East Germany, which was ruled by a communist dictatorship. Gay rights activism there was surprisingly successful.”

Different approaches

Previous historical research has investigated how gay people fared in Germany during the Weimar period, the interwar years that ran roughly from 1918 to 1933, and during Adolf Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship. But little work has been done on the post-war period, said J.P. Daughton, associate professor of modern European history in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford.

Samuel Clowes Huneke made some surprising finds when he investigated German history during the Cold War. (Image credit: Thomas Newton)

“Many of the things that Sam found are surprising to the way most people typically think of West versus East during the Cold War,” said Daughton, who is one of Huneke’s advisers. “West Germany is often thought of as this beacon of liberalism, but it was anything but liberating toward gay people, especially in the 1950s and 1960s. This gets us thinking about the development of human rights in general and how it functions differently in different places at different times.”

As part of his research, Huneke examined materials from 10 archives in the United States and Germany, including the records of the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police. He also interviewed Germans who lived through the Cold War and reunification periods.

The twin Germanies split on how they approached homosexuality as soon as the country separated after World War II, Huneke said.

West Germany reinstated former Nazis in government and kept the same strict Nazi-era sodomy laws, which criminalized any act perceived to be homosexual, including kissing and touching. As a result, the West German government prosecuted more than 100,000 gay men between 1949 and 1969, of whom over 50,000 were convicted. About the same number of gay people were prosecuted and convicted during the Nazi dictatorship, according to Huneke.

East Germany, on the other hand, repealed Nazi-era laws in an effort to be perceived as anti-fascist, and it reverted to the more lenient pre-World War II sodomy law, which only criminalized penetrative sex. And by 1957, East German officials stopped prosecuting consensual adult same-sex relations altogether, Huneke said.

“East Germany was sort of stuck between a rock and a hard place,” Huneke said. “On the one hand, it wanted to live up to this anti-fascist legacy, but it was also a brutal dictatorship that didn’t want to appear to be gay-friendly. So they took a reactive approach. In general, they seemed to let gay people be, unless someone who was connected to the regime was accused of being a homosexual.”

Bumpy road to progress

West Germany’s gay rights movement in the 1970s inspired activists in the East, who eventually formed pro-gay rights organizations of their own.

While the West’s activism died down after 1980, when a group of pro-pedophilia activists disrupted a major gay rights event in West Germany’s capital Bonn during that year’s federal election, activists in the East continued to organize, Huneke said. That work included meeting in Protestant churches, which were somewhat independent from the communist regime, and sending letters to officials with their demands.

East German officials largely dismissed the activists at first. But in an effort to stop them from organizing politically, officials eventually gave in to their demands, Huneke said. From 1985 until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the East German government released a cascade of pro-gay policy changes, granting gay people the right to serve in the military, among other freedoms, according to his research.

As a result, more West German gay people started visiting East Germany in the 1980s, Huneke said.

“This history troubles our assumptions about gay liberation and how minorities fare under certain forms of government, as well as our lingering Cold War expectations about communist and democratic regimes,” Huneke said. “Human rights progress more unevenly than we think. You can have a dictatorship that all of the sudden starts awarding rights to a minority even as its democratic neighbor isn’t.”