The 18th century may not come to mind in a conversation about social networks. But Stanford historian Caroline Winterer sees the period as the first age that witnessed extensive communication among people across the world.

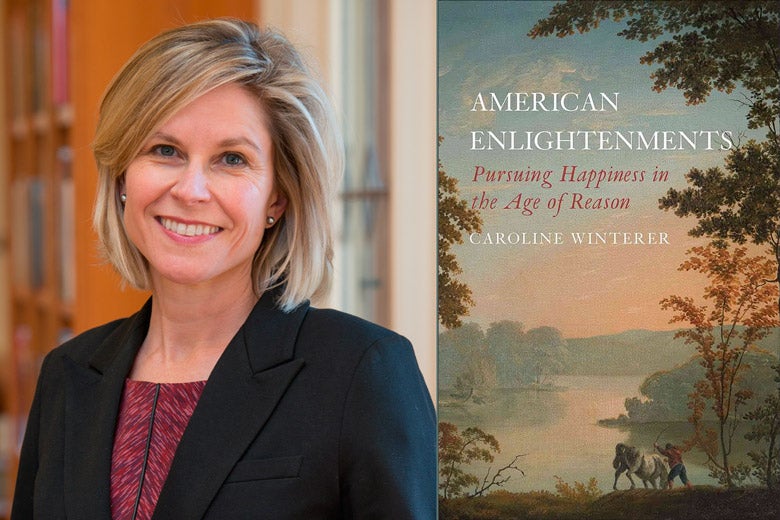

Stanford historian Caroline Winterer says 18th-century polymath Benjamin Franklin’s sizable social network and endless curiosity make him relatable to our networked world today. (Image credit: Steve Castillo)

Hand-written letters were the social media posts of that time, and a new social platform of the era was the United States Postal Service.

Benjamin Franklin, a founder of the USPS, was at the center of that increased communication. Franklin, well known as one of the country’s founders and for his early experiments with electricity, also invented practical objects such as bifocals, among many other achievements.

But what made him especially stand out is the size of his social network and his endless curiosity, according to Winterer, the Anthony P. Meier Family Professor in the Humanities.

“Franklin knew he would be nothing without the people around him,” said Winterer, who is also director of the Stanford Humanities Center. “That’s something we can all learn from today.”

Over the past decade, Winterer has dived into the depths of Franklin’s mind by examining thousands of his letters. During his lifetime, Franklin sent and received somewhere around 20,000 letters.

Winterer recently talked about her research in a lecture titled “The Remarkable Genius of Benjamin Franklin.” Her latest book on the American Enlightenment discusses the role of Americans in the social network revolution during the 18th century. This year also marks 275 years since Franklin helped to found the American Philosophical Society, the oldest learned society in the United States.

Stanford News Service interviewed Winterer about her research on Franklin.

How and why did you start researching Ben Franklin’s letters?

I’m a scholar of American history during the 18th and 19th centuries. But I never specialized in Franklin until about 10 years ago, when I joined Mapping the Republic of Letters, which is a Stanford project that has been harnessing big data technology to analyze the circulation of people, letters and objects during the 17th and 18th centuries.

When I started this project, Franklin was the only major U.S. founder whose papers were mostly digitized and were not hidden behind a paywall. So my then-graduate student Claire Arcenas and I picked him because of the public availability of his work at the time. We wanted this research to be open to everyone who could look at the data and perform their own experiments.

Mapping the source and destination of many of his 20,000 letters changed the way we look at Franklin. Suddenly, Franklin was not just a man in spectacles sitting quietly in his chair or flying a kite. He was a man with a dynamic social network – he was relatable in a new way to our networked world today.

Benjamin Franklin, oil on canvas portrait by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, c. 1785 (Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

What have been some of the takeaways from that research so far?

We can think of the 18th century as the first great age of social networks for several reasons. What constitutes a social network is a point of debate, but I would argue that the 18th century was especially significant when it comes to people communicating with each other.

Literacy rates were starting to reach modern levels for the first time in world history. It was also the age when archives really got going because new nations wanted to preserve the record of their founding. That’s why letters from this century are preserved relatively well. And the creation of a robust mail infrastructure made it possible for more people to send more letters.

It was a time when it started to become more and more common for very connected people, like Franklin, Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson, to have correspondence networks that numbered in the tens of thousands of letters. This would have been pretty unusual even just a century before. There simply wasn’t the infrastructure for a single individual to be able to send and receive that many letters, unless you were a really exceptional person.

Franklin was in the middle of all of that. He served as the postmaster for North America when the colonies were under British rule, and he was instrumental in establishing a postal service system, known today as the United States Postal Service. But he also used letters strategically, to get things done in the world. A lot of Franklin’s letters basically say things like, “Please introduce me to this famous person. Please share my ideas with that influential person.” If there had been LinkedIn, he would have signed up.

As part of your recent lecture, you asked whether Franklin would be considered a genius today. What do you think? Why do you think he became so famous?

Genius is not a constant. It’s not an objective category like “wet” or “dry.” Different societies at different points in time decide who is a genius and who isn’t a genius. In Franklin’s era, they threw the word “genius” around a lot, but they often meant something different than we do today. For them it could also mean “talent” or “inspiration.”

So when we ask if someone in the past was a genius or not, we have to be aware that we are asking a modern question. For modern readers what stands out about Franklin is what an incredibly curious and sociable person he was.

The Stanford library has a letter he sent to a physician in South Carolina that shows some of that curiosity and sociability. In that eight-page letter, Franklin revealed his theory about how digestion works, because he was trying to understand the effect of electricity in the human body. I loved reading that. He was always trying to connect everything and everybody.

His curiosity, his level of communication with others and his ability to expand his social network is something that we can all learn from today.

This was a person who was fully aware that sharing knowledge benefits everybody.

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu