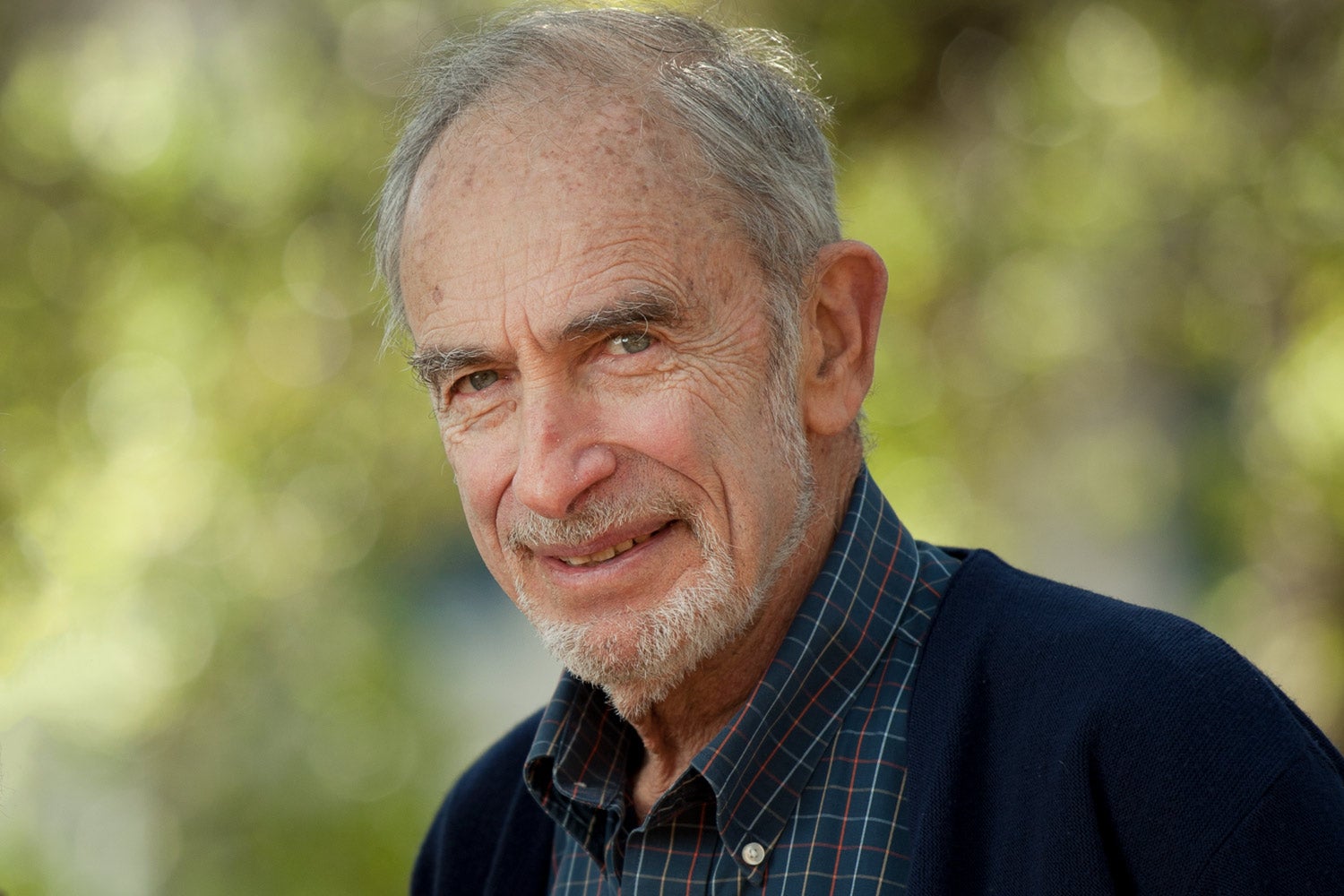

Our jaws are becoming too small. At least, that is what Stanford’s Paul Ehrlich, the Bing Professor of Population Studies, Emeritus, believes. Working with orthodontist Sandra Kahn, Ehrlich has spent years studying the connection between underdeveloped jaws, modern life and myriad health and quality-of-life issues. This research is the subject of Kahn and Ehrlich’s new book, Jaws: The Story of a Hidden Epidemic.

In a new co-authored book, biologist Paul Ehrlich describes the connection between underdeveloped jaws, modern life and myriad health and quality-of-life issues. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

In their book, Kahn and Ehrlich make the case that crooked teeth (and braces) are a modern problem caused primarily by eating soft foods, living in confined spaces with allergens and poor posture, including mouth breathing. The authors declare this an epidemic, linking undersized jaws to increased risk of heart disease, hyperactivity, sleep deprivation and other issues that are endemic to modern life.

Stanford News spoke with Ehrlich about the evidence he and Kahn present in this book and what he wants people to take away from this work.

The major claim of the book is that you and Sandra Kahn have unearthed a hidden epidemic in which people’s lifestyles are affecting how their jaws develop, with many downstream health consequences. What do you feel is the most convincing evidence of that?

I think the best evidence comes from human ancestors. Richard Klein, Stanford paleontologist and the world’s expert on the human fossil record, said to me, “I’ve never seen a hunter-gatherer skull with crooked teeth.”

Studies of skulls from just a few hundred years ago compared with today show human jaws are still shrinking. There hasn’t been time for this to be a genetic problem. You can get crowded jaws within a generation. So, it’s primarily a response to environmental changes accompanying a sedentary life and industrialization.

You’re connecting reduced jaw size with stress and associated health risks. How is it possible for all of those things, which seem so disparate, to be linked?

We know a smaller jaw makes you more susceptible to sleep apnea and so it relates to an area Robert Sapolsky has pioneered: the importance of stress. We now know clearly that having your sleep interrupted is a big stressor and can lead to greater susceptibility to infections and diseases.

We’d like to know more about how stress and sleep apnea – and therefore also jaw size – add to specific health issues, such as cardiovascular problems; behavioral problems, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; and other diseases, possibly even cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

You rely on anecdotal evidence and some clinical outcomes and are upfront about the level of speculation in the book. Why are you talking about this now instead of waiting for more robust studies?

Why wait? I don’t think most of the experimental research you’d need to further support the theory would be ethical or change our basic conclusions. But many important scientific issues don’t involve the sort of ritualized scientific method that kids learn. On the Origin of Species hasn’t got a single experiment in it.

What we do have are natural experiments, anecdotal evidence and speculation. For example, in Jaws, we show pictures of a grandfather who was raised in a traditional habitat with traditional diets, then his son who moved into an industrialized area – with much softer foods – and you can see the deterioration of the son’s face and jaws. His grandchild then had even more problematic jaws.

Introducing a near-liquid diet has been a natural experiment. Lack of chewing naturally influences jaw development just as not walking would change leg development.

Another example: We know from fossil evidence that hunter-gatherers had big, well-developed jaws. Snoring is a symptom of your tongue being too big for your jaw and we speculated that individuals with small jaws wouldn’t have survived since snoring would have attracted leopards, which hunted them.

How does this work on jaw size compare to other public health work you’ve done?

The stakes aren’t as high as with something like climate disruption, which could lead to billions of premature deaths. But Jaws describes an epidemic that is causing a lot of expense – think braces – and misery. Many people’s lives could be improved if it were dealt with. It’s also a public health problem where some of the power to avoid it rests in your own hands.

What can people do to prevent this problem?

Parents should watch their kids for signs that their jaw development is going in the wrong direction, such as mouth breathing, “gummy” smiles, trouble sleeping and morning tiredness. Snoring in kids is a strong danger sign. Get help early.

From birth, encourage children to keep their mouths closed when they’re not eating or talking. This will support proper oral posture, which is lips closed, tongue on the palate, and teeth lightly touching. And wean to tough foods that require chewing, like they did in the days of hunter-gatherers.

You should try to reduce exposure to allergens and consider breathing exercises designed to improve nose breathing and breathing efficiency, like good oral posture exercises. And you can do something that my parents would have hated: Recommend that your kids chew gum.

We can also convince baby food manufacturers to develop foods that are nutritious and safe, and yet require a child to chew a lot. We can make sure schools have chairs that produce the right kind of posture in kids because that seems to affect the oral posture as well. It’s a place where society, if it pays attention, can do a lot.

Ehrlich is faculty in the School of Humanities and Sciences and also a fellow of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.