A campus gathering for former Stanford Police Chief Marvin L. Herrington, who was known for his calm, nonconfrontational and often innovative approach to conflict resolution, will be held from 4 to 6 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 20, in McCaw Hall in the Arrillaga Alumni Center.

All members of the Stanford community are invited to join Herrington’s family, friends and colleagues to commemorate his life and 30-year service to Stanford.

Marvin L. Herrington served as head of the Department of Public Safety for 30 years under four Stanford presidents. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Herrington died Dec. 27 at his campus home surrounded by family. He was 81.

Herrington arrived on campus in 1971, when anti-war demonstrations, sit-ins and vandalism were daily events. He restructured the police force to emphasize community service and rebuilt the university’s Department of Public Safety.

Herrington served under four Stanford presidents – Richard W. Lyman, Donald Kennedy, Gerhard Casper and John L. Hennessy.

In 1994, Stanford awarded Herrington the Kenneth M. Cuthbertson Award for Exceptional Service to the Stanford Community. The citation praised Herrington for “his gentle graciousness, extraordinary sensitivity and his deep respect for human rights for all people.” The award also praised “his quiet, behind-the-scenes efforts – from earthquake preparedness and disaster planning to alcohol awareness and rape prevention – to make the Stanford campus a safe place to work, to study [and] to live.”

Herrington was known for his no-nonsense, nonconfrontational approach.

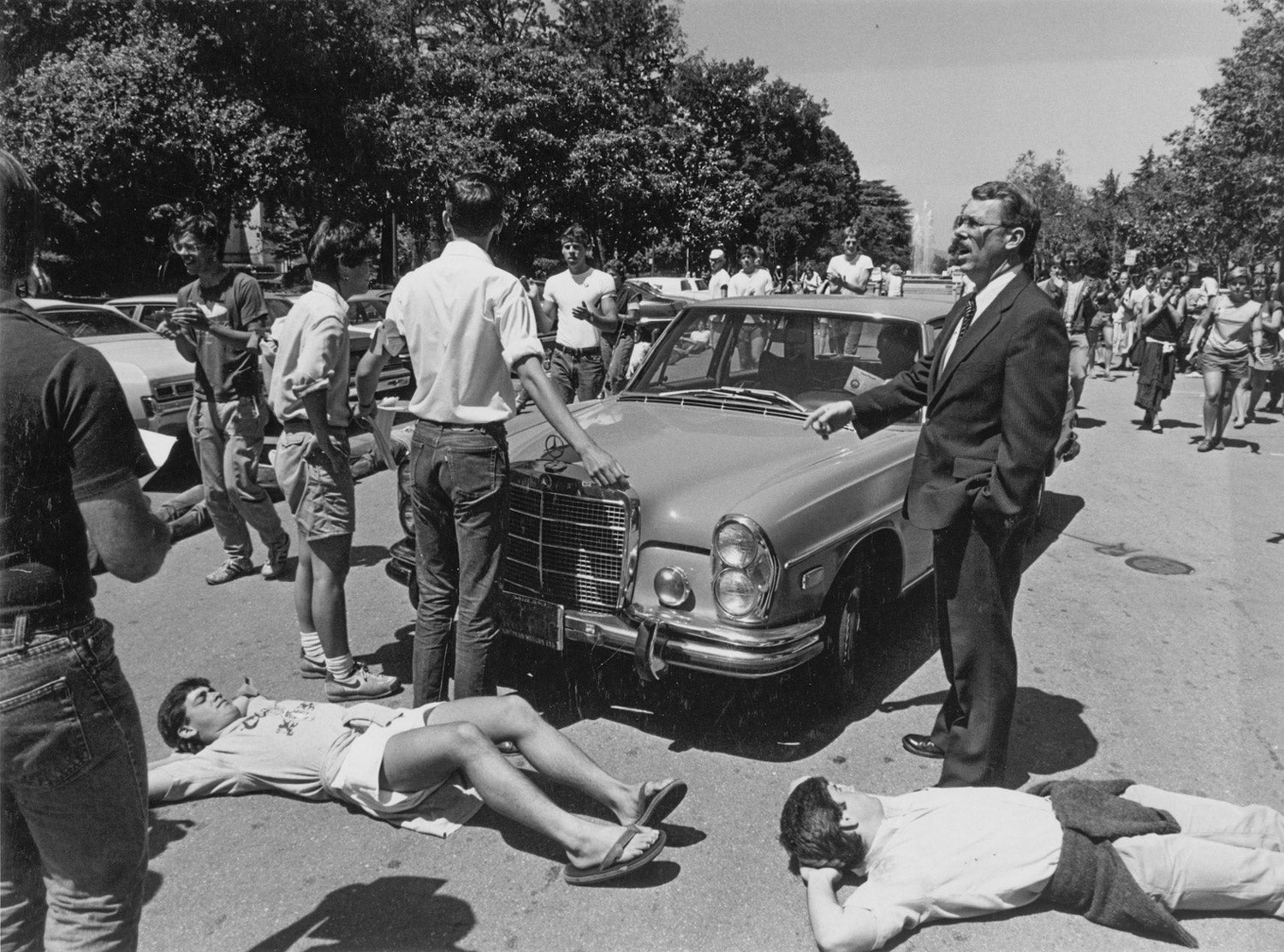

In April 1985, students protesting university investments in South Africa block trustees’ cars. At right is Police Chief Marvin Herrington. (Image credit: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service)

In the 1980s, students regularly protested against Stanford’s investments in companies doing business in South Africa under apartheid. During a Board of Trustees meeting at the Hoover Institution, a group of students organized a sit-in to block the members from returning to their cars nearby. When a discussion ensued about how to process the students, Herrington suggested it would be cheaper to get another bunch of cars. Trustees left unhindered, leaving the protesters sitting around the unused cars. When the students asked, “Aren’t you going to arrest us?” Herrington replied, “We’ve decided not to.”

When Herrington retired in 2001, admiring colleagues said he had brought respect to policing at Stanford.

One former colleague described Herrington’s approach to a perennial campus challenge – teaching students how to be responsible drinkers and enforce the law. During meetings at fraternity houses, Herrington would tell members that knew people from outside campus might show up at their party and cause trouble. “He’d say, ‘If you get in a jam, call us and we’ll help you,’” the colleague recalled. “Frats would see him not as the enemy but as somebody to turn to. He could relate to that kind of student situation comfortably. He enjoyed all kinds of respect.”

In a 2001 interview with Stanford Report, Herrington said he applied the same philosophy in all situations, including high-security visits by world leaders, popular sporting events or student demonstrations in White Plaza.

“What I want is for law enforcement to be even-handed,” he said. “I don’t want police officers to decide what’s right and what’s wrong. The law decides that. I don’t care what the cause is; I’ve got to be the calm one in the situation. I’ve got to deal with the behavior so people don’t get hurt.”

In recent years, the Stanford Historical Society videotaped interviews with Herrington as part of its Oral History Program, which explores the institutional history of the university through interviews with leading faculty, staff, alumni, trustees and others.

In the interviews, Herrington recalled planning the security for big sporting events held in Stanford Stadium, including Super Bowl XIX in 1985 and the 1994 regional World Cup soccer matches, and for campus visits by U.S. presidents and foreign dignitaries, including Mikhail Gorbachev, François Mitterrand, the 14th Dalai Lama and Queen Elizabeth II.

Laura Wilson, Stanford’s director of public safety, served under Herrington for 10 years.

“When I was a relatively new and inexperienced deputy, Chief Herrington gave credit to a deputy for solving a case – even though the chief was the one responsible for suggesting the way to identify the suspect, who had been frightening women on campus for years,” she said. “Marv’s selflessness in that situation made a huge impact on me about what it means to be a leader. While he had a remarkable 30-year career as the chief, what impressed me the most about him was his grace and his humility as a leader.”

Herrington, who grew up in Detroit, began his career in law enforcement in higher education in 1961 as a police officer at the University of California, Davis, where he rose through the ranks to become police chief. After a short stint as director of security at Northwestern University in Illinois, Herrington returned to California in 1970 as coordinator for security for California State College in Los Angeles.

While working in Davis, Herrington earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration in 1968 at Sacramento State College. In 1977, he graduated from the FBI National Academy after completing a professional program for police officers. He earned a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Southern California.

Herrington was devoted to his friends and family, and will be remembered for his passion for books, wood craftsmanship and poker. His family, which enjoyed hiking together throughout California, said he loved playing jokes on family members.

Herrington is survived by his wife of 59 years, Esther, of Stanford; daughters Laura Herrington of Stanford, Dena Zacanti of Los Altos, California, Susan Cordier of Davis, California, and Jennifer Shannon of Loveland, Colorado; and four grandchildren.

The family suggested donations in his memory may be made to further the research of the Alzheimer’s Association, 2290 N. First St., Suite 101, San Jose, CA 95131.