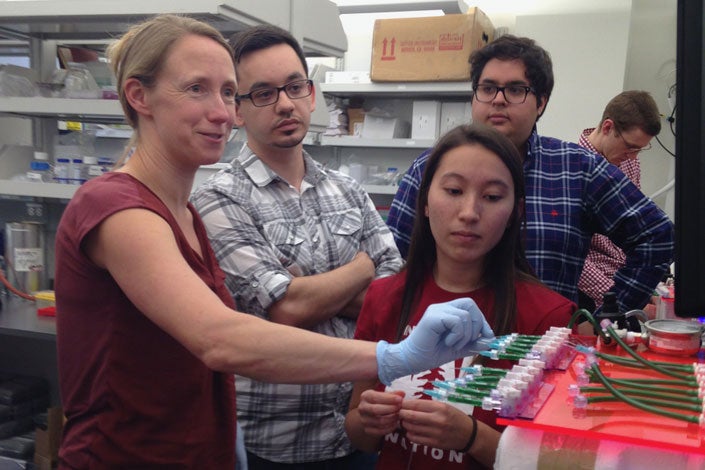

Polly Fordyce (left), assistant professor of bioengineering and of genetics, and graduate students Louai Labanieh, Sarah Lensch and Diego Oyarzun discuss the design of a microfluidic device built to study coral bleaching. The device was designed and built as part of Fordyce’s graduate-level microfluidics course. (Image credit: Courtesy Polly Fordyce)

Team Traptasia had a problem: The tiny baby sea anemones they were trying to ensnare are, unlike their adult forms, surprisingly powerful swimmers. They are also, as team member and chemical engineering graduate student Daniel Hunt put it, “pretty squishy little deformable things.” Previous attempts to trap the anemones, called Aiptasia, while keeping them alive long enough to study under a microscope had ended in gruesome, if teensy, failure.

But Traptasia had to make it work. Cawa Tran, then a postdoctoral fellow, and her research into climate change’s effects on coral bleaching were depending on them. (Sea anemones, it turns out, are a close relative of corals, but easier to study.)

And then there was the matter of the team’s grades to consider, along with the outcome of an experiment in the “democratization” of a powerful set of tools known as microfluidics.

Democratizing science

Team Traptasia was part of a microfluidics course dreamed up by Polly Fordyce, an assistant professor of genetics and of bioengineering and a Stanford ChEM-H faculty fellow.

At the time, she was feeling a bit frustrated.

“Microfluidics has the potential to be this really awesome tool,” Fordyce said. That’s because microfluidic devices shrink equipment that would normally fill a chemistry or biology lab bench down to the size of a large wristwatch, saving space and materials, not to mention time and money. They also open up entirely new ways to conduct biological research – trapping baby sea anemones and watching them under a microscope, for example. But making high-quality devices takes expertise and resources most labs don’t have.

“There’s this big chasm between the bioengineers that develop devices and the biologists that want to use them,” Fordyce said. Bioengineers know how to design sophisticated devices and biologists have important questions to answer, but there is little overlap between the two.

To bridge the gap, Fordyce invited biology labs to propose projects to students in her graduate-level microfluidics course. The idea, she said, was to give students real-world experience while giving labs access to technology they might not have the time, money or expertise to pursue otherwise.

In fact, the desire to break down disciplinary boundaries was something that attracted her to Stanford and to ChEM-H in the first place. “One of the reasons that I came to Stanford and ChEM-H was that I really love the idea of having interdisciplinary institutes that attempt to cross the boundaries between disciplines,” she said.

Ultimately, researchers from four labs took part, including Tran, who was working in the lab of John Pringle, a professor of genetics. Fordyce will be describing her experiences teaching that class in an upcoming paper, which she hopes will provide a blueprint for people eager to help others make use of microfluidics tools.

Shrinky Dinks vs. Aiptasia

Before linking up with Fordyce’s class, Tran had been working with Heather Cartwright, core imaging director at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Plant Biology. Together they tried a more do-it-yourself approach involving the children’s toy Shrinky Dinks, an approach first proposed by Michelle Khine at the University of California, Irvine.

The effort did not work. “We got some movies. They were mostly end-of-life movies,” Cartwright said.

If Tran and Cartwright managed to trap Aiptasia, their Shrinky Dink device crushed or twisted the sea anemones apart. So when Fordyce approached them to work with what would become Team Traptasia – graduate students Salil Bhate, Hunt, Louai Labanieh, Sarah Lensch and Will Van Treuren – and Stanford’s Microfluidics Foundry, they jumped at the chance.

A non-smashing success

Team Traptasia, Tran said, solved her problem “completely.”

After several rounds of design, troubleshooting and testing, Team Traptasia built a microfluidic device that kept Aiptasia alive and healthy long enough to study. As a result, the researchers could actually watch the effects of rising water temperature and pollution on living sea anemones and their symbiotic algae – something that has never been done before. Tran, Cartwright and Team Traptasia will publish their findings soon, Tran said.

A young Aiptasia sea anemone ejects algae (highlighted in blue-green) in response to changing water conditions. (Video credit: Cawa Tran and Heather Cartwright)

Other teams helped labs design devices to study how the parasite that causes toxoplasmosis infects human cells, to trap and study placental cells, and to isolate single cells in tiny reaction chambers for detailed molecular biology studies.

Tran said the device Team Traptasia came up with could provide opportunities for the Pringle lab, as well as in education. Now an assistant professor at California State University, Chico, Tran said she’ll be using the device with undergraduates there. “Basically, this device has given me the opportunity to train the next generation of biologists” in a new, research-focused way, she said.

Hunt, the chemical engineering student in Team Traptasia, said that his own research on intestinal biology could benefit from microfluidics. “I’m hoping to take the expertise that I gained in the microfluidics design process to my own research,” he said. Hunt is working in the lab of Sarah Heilshorn, an associate professor of materials science and engineering.

Those are exactly the kinds of results Fordyce had hoped for.

“This year was successful beyond my dreams, and the reason is that the students in the course were incredibly creative and talented and driven,” Fordyce said. She also credits her graduate student and teaching assistant Kara Brower, who won a teaching award for her efforts. “She went way above and beyond what would be required of a TA and really helped imagine and develop the course,” Fordyce said.

“If you put this forward as a model for people at other schools, that could actually make a difference,” both for students and the labs that could benefit from microfluidics, she said.

Fordyce and Pringle are also members of Stanford Bio-X.

Media Contacts

Nathan Collins, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-9364, nac@stanford.edu