In 1972, the American public learned that the United States government let hundreds of black men go untreated for syphilis as part of a research experiment.

Stanford historian Londa Schiebinger’s new book traces the history of medical experimentation on slaves on Caribbean plantations. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

The memory of the shocking Tuskegee syphilis study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service, endures, especially in African American communities.

The study was also on the mind of Stanford history Professor Londa Schiebinger when she stumbled upon archives documenting a British doctor’s smallpox experiments on 850 slaves in 18th-century rural Jamaica.

Schiebinger embarked on a mission to learn how medical knowledge was created in the British and French colonies during that time and whether large populations of slaves underwent medical testing. Schiebinger’s findings were recently published in her new book Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the 18th-century Atlantic World.

Stanford News Service interviewed Schiebinger, the John L. Hinds Professor of History of Science, about her research:

What’s the biggest takeaway from your research?

Knowledge is developed within a cultural context, which means that the best ideas don’t always win out. This point is obvious when studying something like colonial science or medicine. But understanding these extreme cases helps us evaluate our own institutions, blind spots and untapped areas for new discoveries.

British vaccinator Edward Jenner used this lancet during inoculations. (Image credit: Courtesy Wellcome Library, London)

Tell us about the case that inspired you to do this research.

Research for a new book often starts with a “find.” While researching for my previous book, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World, I stumbled upon John Quier’s experiments with smallpox inoculation in a population of 850 slaves. Quier was a British doctor serving as a plantation physician in rural Jamaica. Recalling the Tuskegee syphilis study, I wondered if large populations of slaves, concentrated on American plantations in the 18th century, were used as human guinea pigs.

Quier carried out his mass inoculations — a precursor to vaccine — beginning in 1768 as an epidemic swept across Jamaica. Quier was employed by slave owners and would have inoculated for smallpox with or without his scientific experiments. Importantly, slave owners had the final word. There was no issue of slave consent or, for that matter, often physician consent. Yet, Quier did some inoculations repeatedly on the same person and at his own expense. He took risks beyond what was reasonable to treat the individual patient. Throughout his experiments, when pressed, Quier followed the science and not necessarily what was best for the human being standing in front of him.

To what extent were slaves exploited in 18th-century medical experiments?

While I would not want to push the argument too far, it seems that slaves were protected to a certain extent from excessive medical exploitation. Slaves were valuable property of powerful plantation owners. The master’s will prevailed over a doctor’s advice and colonial physicians did not always have a free hand in devising medical experiments. Nonetheless, we find numerous exploitive experiments with slaves in this period. We must remember that colonial physicians’ investigations were not purely scientific queries but questions fired in the colonial crucible of conquest, slavery, violence and secrecy.

Slaves were not alone. Many poor souls were subjected to medical testing in this period. In Europe and its American colonies, drug trials tended to over-select subjects from the poor and wards of the state, such as prisoners, hospital patients and orphans.

What were some of the African contributions to science?

My career has been devoted to studying how knowledge is produced: who is included, who is excluded and how cultural assumptions drive research. This book focuses on the circulation of knowledge in the Atlantic world and the competition between African, Amerindian and European knowledge traditions.

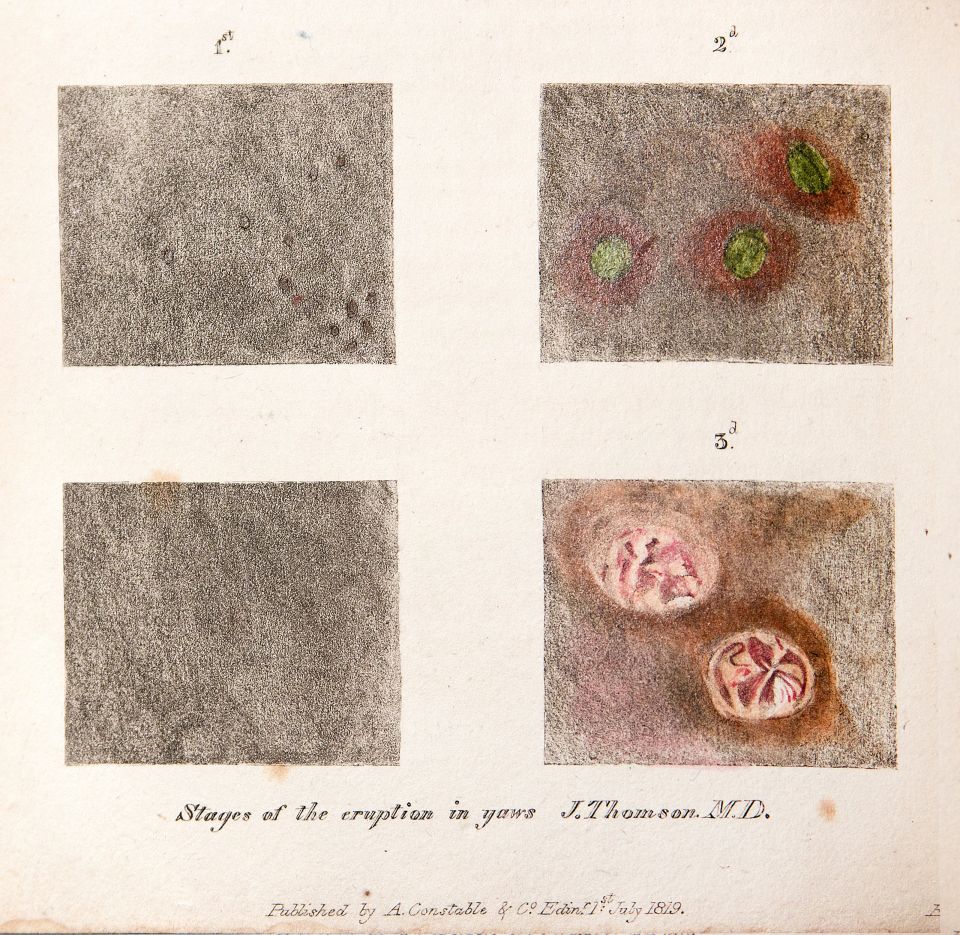

An early drawing by doctor James Thomson shows different stages of yaws, a tropical infection of the skin, bones and joints. (Image credit: Courtesy Stanford Medical History Center)

Interestingly, European physicians knew very little about tropical disease and its cure, but Africans did. During my research, I found an extraordinary experiment that pitted slave cures against European treatments in Grenada in 1773. It was something of a “cure off.” Both cures were designed to treat yaws, a horrid tropical infection of the skin, bones and joints bred in poverty and poor sanitation.

Under the master’s careful eye, two slaves were given to the enslaved doctor for treatment and four to the European-trained surgeon. The outcome? The slave’s patients were cured within a fortnight; the surgeon’s patients were not. The plantation owner, a man of science, consequently put the man of African origins in charge of all yaws patients in his plantation hospital. In the process, the enslaved man — who remained nameless and faceless throughout — was elevated in status to a “Negro doctor.”

What surprised you during the research?

Surprisingly to modern eyes, women were regularly included in medical research in the 1700s. In contrast to today, tests were not unreflectively performed on male bodies and generalized to female bodies. In England, the iconic Newgate Prison trials to test the safety of smallpox inoculation in 1721, for example, selected six condemned criminals, three women and three men, matched as closely as possible for age.

Women were also featured in experiments in the colonies. Quier’s experiments in Jamaica further raised explosive questions about differences among women. Quier’s London colleagues were concerned that experiments done on slave women might not be valid for “women of fashion, and of delicate constitutions.” Treatments appropriate for slave women, they warned, might well destroy ladies of “delicate habits … educated in European luxury.”

Today, medical researchers struggle to include women in clinical trials. It is impossible to say when women were defined out as proper subjects of human research. Exactly how and why will be the next topic historians need to tackle.