Stanford’s East Asia Library recently received a rare collection of diaries kept by a Japanese businessman during the early- and mid-20th century that Stanford professors say can provide a unique perspective on a tumultuous period between the United States and Japan.

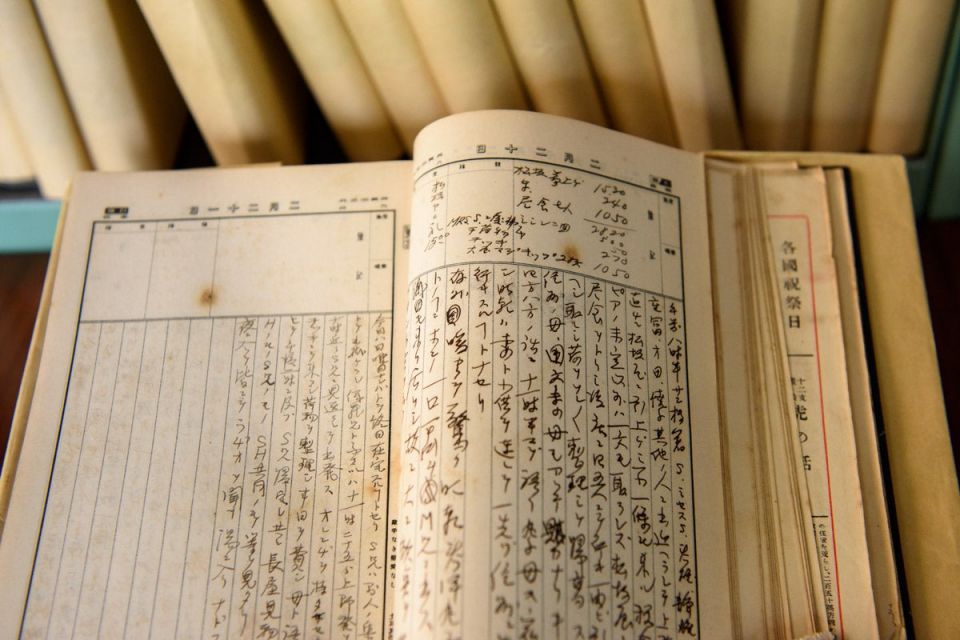

Regan Murphy Kao, curator for the Japanese Collection in the East Asia Library, looks through the Hisao Magario diaries chronicling life in Japan and America. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

“This is marvelous material,” said Gordon Chang, professor of American history. “It illuminates life here in America, but also the sentiments between the U.S. and Japan during that time.”

Chang said more scholars are examining the trans-Pacific relationship and its history; materials like the diaries of Hisao Magario can give an important perspective to that research.

“The Magario diaries are rare and valuable on so many levels,” said Jun Uchida, an associate professor of history, who is currently researching a community of merchants in Japan. “Rarely do scholars encounter diaries kept by an ordinary man who recorded virtually every day of his extraordinary life that spanned the periods before, during and after World War II.”

Magario lived in Oakland and San Francisco between 1920 and 1926, then went back to Japan where he stayed until his death in 1960. According to his relatives, Magario was a dish washer when he came to the U.S., but later established his own business, selling Japanese souvenirs and other goods.

Diaries kept by Hisao Magario, second from right, and his wife, Fusai Magario, right, are now in the collection of Stanford’s East Asia Library. (Image credit: Courtesy of Tsuneo Nakajima)

From 1920 to 1960, Magario meticulously documented his daily routine, including noting the state of the weather and his purchases, in 40 journal volumes.

Uchida, who also serves as director of Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies, said she was particularly struck by Magario’s vivid descriptions of the impact historical events of the time had on his life. When the U.S. passed the Immigration Act of 1924, Magario described the increasing anti-Japanese sentiment that surrounded him. One entry described his landlord increasing the rent price for his store, which Magario later wrote was set on fire. After the passage of the act, he began seriously to think about returning to Japan with his family.

“Diaries offer us historians access to the daily lives of ordinary people that usually go undocumented,” Uchida said. “These unedited sentiments and intimate details can offer us new and surprising insights into the past.”

The diaries, as well as Magario’s family photos, were donated to Stanford with the help of Magario’s grandnephew Steven Yoda, a Stanford alumnus; great-granddaughter, Miki Nakajima; and grandson, Tsuneo Nakajima. The collection also includes diaries from Magario’s wife, Fusai, from 1972.

Yoda’s grandfather, who was the brother of Magario’s wife, stayed in San Francisco and assisted with Magario’s business until Yoda’s family was relocated to an internment camp in the 1940s in Utah.

Yoda, who was born and raised in California, said the two families lost touch over time, and he said the little he knew about Magario was from old family photos.

“He was always this mysterious uncle with a mustache to me,” Yoda said. “I’ve seen his pictures growing up, but I didn’t know much about him. I just knew that everyone in my family was thankful for him.”

But, after almost a century of separation, the two halves of the family reunited. In 2013, Miki Nakajima came to California to pursue her doctoral degree at the California Institute of Technology. Nakajima, who grew up in Tokyo, reached out to Yoda.

“We had a lot of pictures and stories to share,” Nakajima said. “But it was also very interesting to see our different cultural backgrounds – for example, when I first met Steve, I was not sure if I should bow or shake hands.”

In 2015, Nakajima told Yoda about Magario’s diaries and that the family was trying to find a way to preserve them.

Yoda, who studied Japanese and Asian American history at Stanford and wrote his undergraduate honors thesis about the Japanese internment, said he realized the importance of his great-uncle’s journals instantly.

“I thought we were sitting on a treasure of interesting information,” said Yoda, who suggested the family donate the materials to Stanford for research.

Yoda said his family’s story isn’t unique. World War II and the strained U.S.-Japanese relations led to many families separating from each other.

“For many of us, the history of how we got to the United States was lost,” Yoda said. “I thought it was lost for me. And I feel really lucky that one of my ancestors left a written record like this that we can now read.”

The donated diaries are available for review at the East Asia Library and can be viewed online through Stanford Libraries’ catalog SearchWorks.

Media Contacts

Gabrielle Karampelas, Stanford University Libraries: gkaram@stanford.edu, (650) 492-9885

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: ashashkevich@stanford.edu, (650) 497-4419