For more than 600 years, the Ottomans ruled over a multilingual and multicultural empire.

Mahmud II was sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 to 1839, a period overlapping the Age of Revolution. (Image credit: John Young, "A Series of Portraits of the Emperors of Turkey.")

With its dominant center in Istanbul and stretching over parts of North Africa, southeastern Europe and western Asia, the empire peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Then, between 1760 and 1820 – as revolutions were erupting around the world – the Ottomans attempted reform. According to a new study by Ali Yaycioglu, assistant professor of history at Stanford, this complex transitional period uncovers the origins of modern political culture in the region.

“The late 18th and early 19th centuries are very important to understand democratic culture in the region that includes the Balkans, Turkey and the Arab world,” Yaycioglu said. “Studying this period in Ottoman history is vital to understand the region in the present day.”

This particular moment in Ottoman history drew the attention of Yaycioglu because the Age of Revolution is generally associated with Europe and the Americas, and particularly with the French and American revolutions.

“In the Ottoman Empire there was not a revolution that toppled the central government, but rather a significant number of reforms and transitions related to the globalized context of revolutions and modernization across the world,” Yaycioglu said.

In his recent book, Partners of the Empire: The Crisis of the Ottoman Order in the Age of Revolutions, Yaycioglu traces the complex social and political changes of the period.

To do so, he rummaged through archives, uncovering records that document the many, ultimately abortive, attempts to decentralize the imperial government. Of particular interest to Yaycioglu was the failed Deed of Alliance (Sened-i Ittifak) of 1808, which he compares to better-known documents of the time, such as the French Constitution of 1791.

A failed partnership

The Deed sought to resolve a constitutional crisis and uprisings brought on by attempts to reform and modernize the empire between 1806 and 1808.

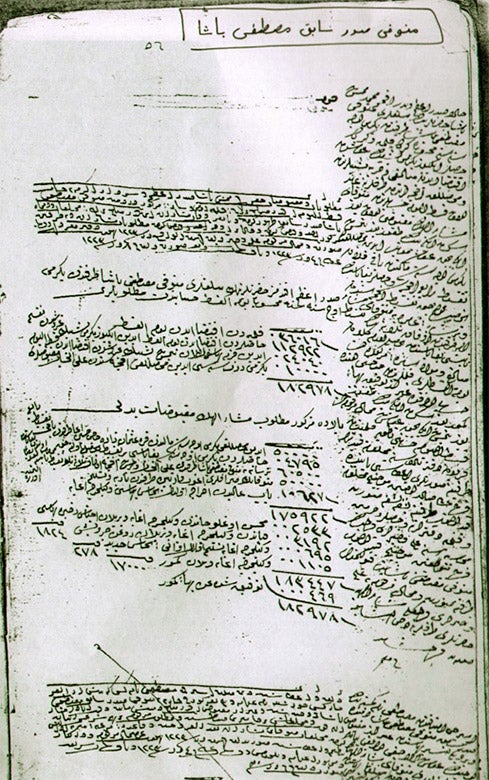

Mustafa Pasha Bayraktar, architect of the Deed of Alliance, wrote this Inheritance Register. (Image credit: Prime-Ministry Ottoman Archives, Istanbul)

In theory, the Deed aimed to stabilize the empire by shaping an alliance between imperial reformists, who held power, and provincial power holders, who had regional control but lacked influence in the central government. This new alliance would be based on shared resources, collective responsibility, security and mutual trust.

“The provincial nobles claimed that they were partners of the empire, shareholders in the larger picture. The state, however, continued to think of them as servants,” Yaycioglu said. “The Deed shows the dynamic between various parties in the empire and the relationships of power. If this moment had prevailed, there might have been a new form of imperial unity, perhaps a federal solution, across this changing and increasingly divided empire.”

Rather than bringing the empire closer together through partnership and cooperation, the Deed was not universally accepted and its failure led to further divisions, leading to the empire’s eventual dissolution after World War I.

For Yaycioglu, the Deed was a short-lived attempt to make the empire more inclusive by involving regional leaders, themselves engaged in a “struggle for rights and recognition.”

As with the earlier reform attempts, the Deed sparked a revolt among the empire’s elite infantry units, known as Janissaries. By 1809, the Sultan Mahmud II had scrapped the Deed, pacifying or otherwise eliminating provincial “partners.”

There was neither revolution nor unification, but rather an exposure of complex power relations in the empire. Some provincial leaders willingly abandoned their autonomy. Others retained power, but aligned themselves with the imperial authorities. Still others vigorously resisted pacification and fought for their regional autonomy and identity, sometimes violently.

Whatever the case, said Yaycioglu, the proposed Deed failed to impose a republican model on the empire that would be resurrected, a century later, in the Turkish republic.

“This moment helps us understand social and political culture in the region until today. It was not as straightforward as ‘failed Westernization,’ as is often claimed,” Yaycioglu observed. “There was more at play. The battle was not between old and new, state and people, elites and the crowd, center and periphery, Muslims and non-Muslims as monolithic blocks.”

“It was not a binary relationship but rather a multifaceted transformation, where the old was mixed with the new, the East with the West,” he added.

Into the archives

To study the Ottoman transition to modernity, Yaycioglu sleuthed through multiple archives.

“I worked with documents reflecting the crises and studied their impact right down to the personal, intimate level. The art of history is to make those connections between different layers and levels of analysis,” Yaycioglu said.

And connect he did, by leafing through documents written in Ottoman-Turkish, Arabic and Greek—the languages that threaded the Ottoman Empire together—all found in archives across Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, Bosnia, Austria, France, Russia and England.

“In the Ottoman context, the Age of Revolution saw the opportunity to acquire power and wealth at the expense of others. The archival records show the winners and losers in such volatile moments,” Yaycioglu said.

Yaycioglu said that much of the historical research on this period lapses into Western categories, such as nation-state versus failed empire or reforms against the status quo, obscuring major achievements the Ottomans made in their final centuries. Although integration stalled, hindered by uprisings and crises of every sort, the empire remained intact but riddled with divisions.

“I found more value in connecting these fields in a holistic fashion rather than separating them,” Yaycioglu said. “The reality of the moment was much more complex than a series of isolated events or institutions.”

Media Contacts

Chris Kark, director of humanities communication: (650) 724-8156, ckark@stanford.edu