The Hellboy comics – about a demon who tries to resist his predestined role to destroy our world – provide a powerful vantage point from which to view the extraordinary and unique powers of the comic book medium, a Stanford scholar suggests.

That is the viewpoint of Scott Bukatman, a Stanford professor of film and media studies. He researched the Hellboy series by creator Mike Mignola and found that the pleasures of reading a comic book can reveal something about contemporary visual culture and even the act of reading itself.

Go to the web site to view the video.

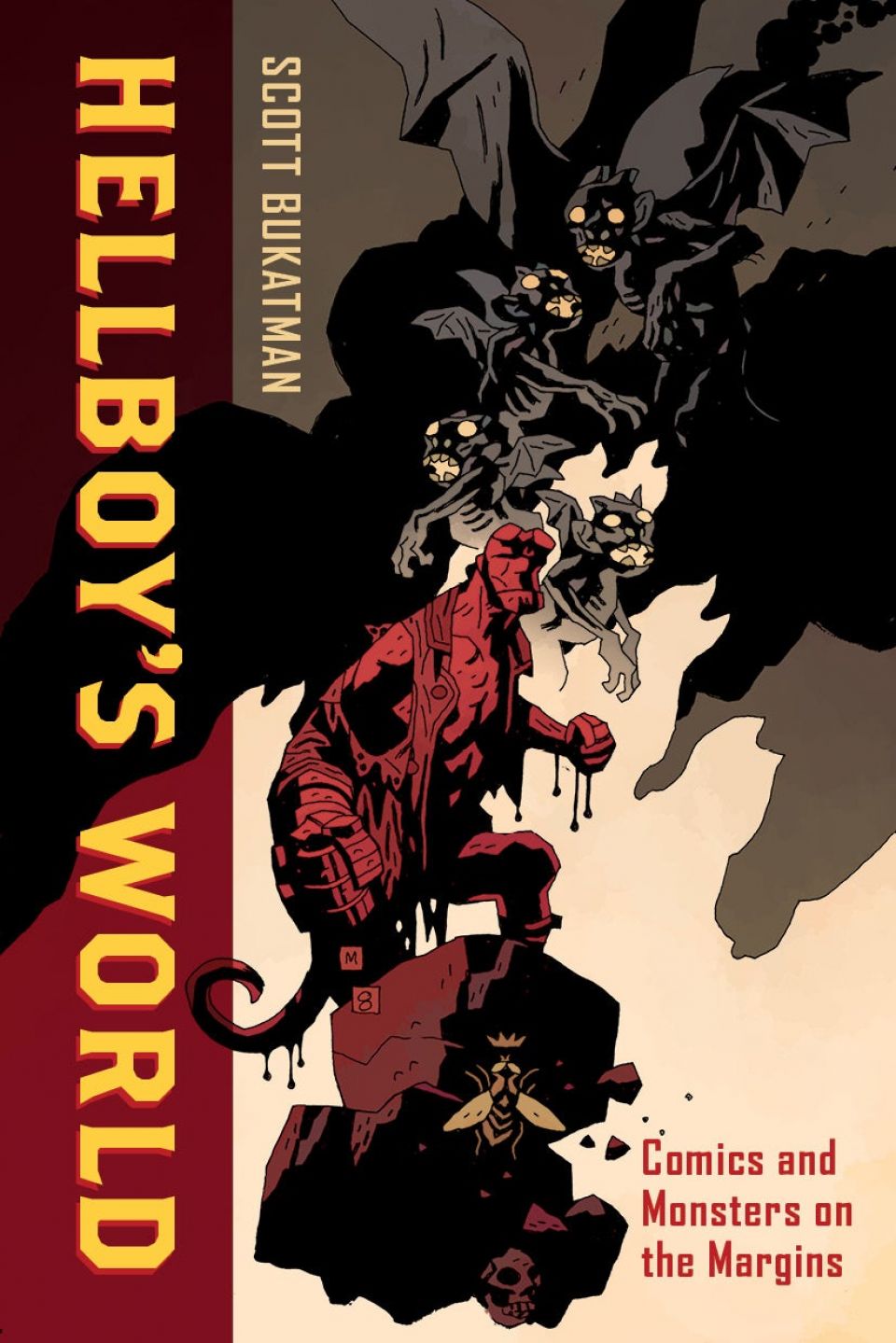

“Trying to understand what comics are in and of themselves is really important because we are in a moment where comics are very, very popular, whether in the new popularity of superheroes, which are now ubiquitous in our culture, or in the graphic novels, memoirs and journalism that have been appearing over the past few decades,” said Bukatman, who details his findings in a new book, Hellboy’s World: Comics and Monsters on the Margins.

Many different genres are juggled in the Hellboy comics and, as a result, the stories themselves have different tonalities, Bukatman said.

“Some are really funny, some are melancholy. Some are cosmic in scope, others are local and small. There’s a lot of variety within this strange story world that Mignola has come up with,” he said.

Mignola also overtly draws upon genre fiction, art history and other comics traditions to build his world; Hellboy‘s world intersects with other aesthetic and literary worlds, according to the Stanford scholar.

Bukatman’s research homes in on the aesthetic space that Mignola creates where he emphasizes the page over the linear sequence of panels, always thinking about the impact of two pages side-by-side.

“The experience of Hellboy is the experience of holding the book open and having two pages in front of you … so that when you’re holding it, you’re immersed in a hugely aestheticized world. In my reading, Hellboy‘s world is the world of the book,” Bukatman said.

Bukatman also emphasizes the color palette that comic colorist Dave Stewart has given Hellboy. Color is an understudied aspect of comics, he points out, even though it has such a visceral impact on readers. He wonders whether American culture’s suspicion of comics has something to do with the lurid colors that marked them in newspapers and comic books.

The color palette in Hellboy illustrates an understudied aspect of comics, says Scott Bukatman, who points out color’s visceral impact on readers. (Image credit: Courtesy Scott Bukatman)

Stillness in comics

As a film studies scholar, Bukatman has explored the similarities between comics and films as types of moving image media. But in Hellboy’s World, he is more concerned with the deep differences between these media.

Though Bukatman acknowledges that a Hellboy comic and a Hellboy film (directed by Guillermo de Toro) are both action-adventure stories, he notes distinct differences between them.

“The movies are highly kinetic, even frenetic, especially the second one [Hellboy II: The Golden Army]: lots of special effects, lots of bustle and noise. The comics, by contrast, are really still and quiet,” he said.

Mignola creates an experience of stillness by avoiding the traditional motion lines (and other cues to motion) that many comic artists use. He does not emphasize deep space, as other comic artists tend to do in an attempt to imitate film. Instead, Mignola renders panels that are “strikingly quiet, flat and still,” Bukatman said.

“The more I thought about the [Hellboy] comics, the more I realized how different they were from the films, different in ways that helped me to think more broadly about the ways these media diverge,” he said.

Bukatman suggests that comic books provide something that film does not: silence – and the freedom of the reader to peruse the world created by the comic, each in his or her own way. Within this silence, the reader’s imagination uniquely animates each panel and page.

Ultimately, Bukatman concludes that the nature of Hellboy‘s aesthetic sophistication is uniquely suited to the printed medium of comics.

Comics in the classroom

Bukatman treats comics as serious objects of inquiry. He emphasizes the acts of watching and reading over the demand to find “meaning” in these kinetic and colorful experiences. How are we animated by films and comics, and how do they animate us?

Hellboy’s World by Scott Bukatman (University of California Press, 2016)

His students have been highly receptive to his approach to culture and film studies. He thinks that they are “appreciative because I do open up ways of approaching culture that are different from the ways they’ve often been taught to do it.”

In addition, he co-founded a student workshop, The Stanford Graphic Narrative Project, that facilitates collaboration among scholars, writers, artists and teachers on topics such as comics, manga, animation and graphic novels.

Bukatman brings a child-like spirit to contemplating serious issues; perhaps not all things require “gravity” to be taken seriously.

He points to the “tendency of scholars to overemphasize seriousness.” By contrast, he respects the lightness of his objects of study.

He wants “to engage with their lightness, and explicate it in a way that never weighs them down, but which continues to respect what they are, be it a Fred Astaire dance sequence or a page of a Hellboy comic or a Bugs Bunny cartoon.

Media Contacts

Scott Bukatman, Department of Art and Art History: xbody@stanford.edu

Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu