René Girard was one of the leading thinkers of our era – a provocative sage who bypassed prevailing orthodoxies and “isms” to offer a bold, sweeping vision of human nature, human history and human destiny.

The renowned Stanford French professor, one of the 40 immortels of the prestigious Académie Française, died at his Stanford home on Nov. 4 at the age of 91, after long illness.

Fellow immortel and Stanford Professor Michel Serres once dubbed him “the new Darwin of the human sciences.” The author who began as a literary theorist was fascinated by everything. History, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, religion, psychology and theology all figured in his oeuvre.

International leaders read him, the French media quoted him. Girard influenced such writers as Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee and Czech writer Milan Kundera – yet he never had the fashionable (and often fleeting) cachet enjoyed by his peers among the structuralists, poststructuralists, deconstructionists and other camps. His concerns were not trendy, but they were always timeless.

In particular, Girard was interested in the causes of conflict and violence and the role of imitation in human behavior. Our desires, he wrote, are not our own; we want what others want. These duplicated desires lead to rivalry and violence. He argued that human conflict was not caused by our differences, but rather by our sameness. Individuals and societies offload blame and culpability onto an outsider, a scapegoat, whose elimination reconciles antagonists and restores unity.

According to author Robert Pogue Harrison, the Rosina Pierotti Professor in Italian Literature at Stanford, Girard’s legacy was “not just to his own autonomous field – but to a continuing human truth.”

“I’ve said this for years: The best analogy for what René represents in anthropology and sociology is Heinrich Schliemann, who took Homer under his arm and discovered Troy,” said Harrison, recalling that Girard formed many of his controversial conclusions by a close reading of literary, historical and other texts. “René had the same blind faith that the literary text held the literal truth. Like Schliemann, his major discovery was excoriated for using the wrong methods. Academic disciplines are more committed to methodology than truth.”

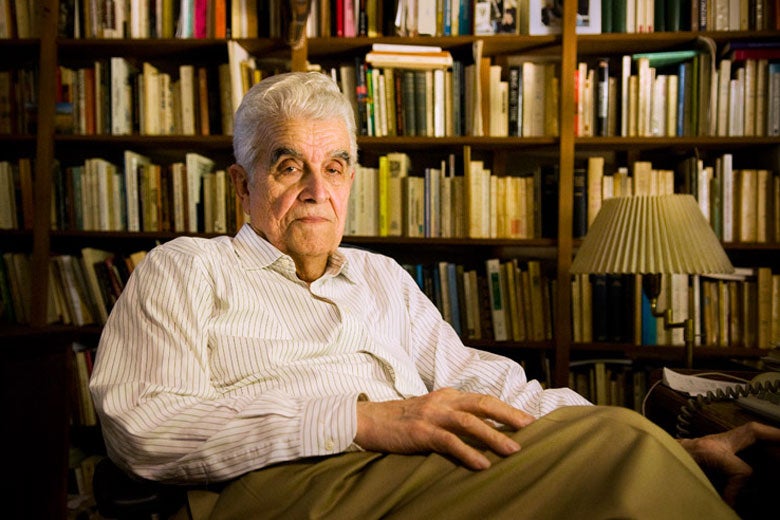

Girard was always a striking and immediately recognizable presence on the Stanford campus, with his deep-set eyes, leonine head and shock of silver hair. His effect on others could be galvanizing. William Johnsen, editor of a series of books by and about Girard from Michigan State University Press, once described his first encounter with Girard as “a 110-volt appliance being plugged into a 220-volt outlet.”

Girard’s first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel (1961 in French; 1965 in English), used Cervantes, Stendhal, Proust and Dostoevsky as case studies to develop his theory of mimesis. The Guardian recently compared the book to “putting on a pair of glasses and seeing the world come into focus. At its heart is an idea so simple, and yet so fundamental, that it seems incredible that no one had articulated it before.”

The work had an even bigger impact on Girard himself: He underwent a conversion, akin to the protagonists in the books he had cited. “People are against my theory, because it is at the same time an avant-garde and a Christian theory,” he said in 2009. “The avant-garde people are anti-Christian, and many of the Christians are anti-avant-garde. Even the Christians have been very distrustful of me.”

Girard took the criticism in stride: “Theories are expendable,” he said in 1981. “They should be criticized. When people tell me my work is too systematic, I say, ‘I make it as systematic as possible for you to be able to prove it wrong.'”

In 1972, he spurred international controversy with Violence and the Sacred (1977 in English), which explored the role of archaic religions in suppressing social violence through scapegoating and sacrifice.

Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978 in French; 1987 in English), according to its publisher, Stanford University Press, was “the single fullest summation of Girard’s ideas to date, the book by which they will stand or fall.” He offered Christianity as a solution to mimetic rivalry, and challenged Freud’s Totem and Taboo.

He was the author of nearly 30 books, which have been widely translated, including The Scapegoat, I Saw Satan Fall Like Lightning, To Double Business Bound, Oedipus Unbound and A Theater of Envy: William Shakespeare.

His last major work was 2007’s Achever Clausewitz (published in English as Battling to the End: Politics, War, and Apocalypse), which created the kind of firestorm only a public intellectual in France can ignite. French President Nicolas Sarkozy cited his words, and reporters trekked to Girard’s Paris doorstep daily. The book, which takes as its point of departure the Prussian military historian and theorist Carl von Clausewitz, had implications that placed Girard firmly in the 21st century.

A French public intellectual in America

René Noël Théophile Girard was born in Avignon on Christmas Day, 1923.

His father was curator of Avignon’s Musée Calvet and later the city’s Palais des Papes, France’s biggest medieval fortress and the pontifical residence during the Avignon papacy. Girard followed in his footsteps at l’École des Chartes, a training ground for archivists and librarians, with a dissertation on marriage and private life in 15th-century Avignon. He graduated as an archiviste-paléographe in 1947.

In the summer of 1947, he and a friend organized an exhibition of paintings at the Palais des Papes, under the guidance of Paris art impresario Christian Zervos. Girard rubbed elbows with Picasso, Matisse, Braque and other luminaries. French actor and director Jean Vilar founded the theater component of the festival, which became the celebrated annual Avignon Festival.

Girard left a few weeks later for Indiana University in Bloomington, perhaps the single most important decision of his life, to launch his academic career. He received his PhD in 1950 with a dissertation on “American Opinion on France, 1940-43.”

“René would never have experienced such a career in France,” said Benoît Chantre, president of Paris’ Association Recherches Mimétiques, one of the organizations that have formed around Girard’s work. “Such a free work could indeed only appear in America. That is why René is, like Tocqueville, a great French thinker and a great French moralist who could yet nowhere exist but in the United States. René ‘discovered America’ in every sense of the word: He made the United States his second country, he made there fundamental discoveries, he is a pure ‘product’ of the Franco-American relationship, he finally revealed the face of an universal – and not an imperial – America.”

At Johns Hopkins University, Girard was one of the organizers for the 1966 conference that introduced French theory and structuralism to America. Lucien Goldmann, Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan and Jacques Derrida also participated in the standing-room-only event. Girard quipped that he was “bringing la peste to the United States.”

Girard had also been on the faculties at Bryn Mawr, Duke and the State University of New York at Buffalo before he came to Stanford as the inaugural Andrew B. Hammond Professor in French Language, Literature and Civilization in 1981.

Girard was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and twice a Guggenheim Fellow. He was elected to the Académie Française in 2005, an honor previously given to Voltaire, Jean Racine and Victor Hugo. He also received a lifetime achievement award from the Modern Language Association in 2009. In 2013, King Juan Carlos of Spain awarded him the Order of Isabella the Catholic, a Spanish civil order bestowed for his “profound attachment” to “Spanish culture as a whole.” He was also a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur and Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres.

Others were impressed, but Girard was never greatly impressed with himself, though his biting wit sometimes rankled critics. Stanford’s Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, the Albert Guérard Professor in Literature, called him “a great, towering figure – no ostentatiousness.” He added, “It’s not that he’s living his theory – yet there is something of his personality, intellectual behavior and style that goes with his work. I find that very beautiful.

“Despite the intellectual structures built around him, he’s a solitaire. His work has a steel-like quality – strong, contoured, clear. It’s like a rock. It will be there and it will last.”

Girard is survived by his wife of 64 years, Martha, of Stanford; two sons, Daniel, of Hillsborough, California, and Martin, of Seattle; a daughter, Mary Girard Brown, of Newark, California; and nine grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held Tuesday, Jan. 19, 2016, at 2 p.m. in Stanford Memorial Church.

Media Contacts

Cynthia Haven, Division of Literatures, Cultures & Languages: (650) 815-9839, cynthia.haven@stanford.edu

Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu