Stanford Professor Emeritus Carl Djerassi, a rare powerhouse in chemistry and art, died peacefully, surrounded by family and loved ones, in his home in San Francisco on Friday. He was 91.

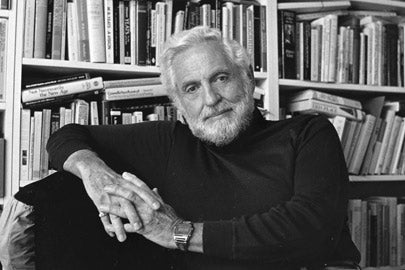

In his long and storied career, Carl Djerassi published more than 1,200 scientific papers, and in doing so transformed the way chemists do their work. (Image credit: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service)

Starting in the 1940s, he was a primary player in synthesizing the first commercial antihistamines, and the hormones cortisone and norethindrone, the latter being the chemical basis of oral contraceptives, earning him the nickname “The Father of the Pill.”

Always seeking a new challenge, he spent the final decades of his life writing many successful novels, poems and plays, which have been performed around the world and translated into several languages.

“Carl Djerassi was first and foremost a great scientist. Together with his colleagues, he transformed the world by making oral contraception effective,” said Stanford President John Hennessy. “Later in life, he became a great supporter of artists and a playwright whose plays entertained while they also educated.”

Friends and colleagues described him as a brilliant and elegant man, always with a twinkle in his eye and a comment to take the listener off-guard.

“Carl Djerassi is probably the greatest chemist our department ever had,” said Richard N. Zare, the Marguerite Blake Wilbur Professor in Natural Science at Stanford. “I know of no person in the world who combined the mastery of science with literary talent as Carl Djerassi. He also is the only person, to my knowledge, to receive from President Nixon the National Medal of Science and to be named on Nixon’s blacklist in the same year.”

Djerassi’s death resulted from complications due to cancer. He is survived by his son, Dale Djerassi; stepdaughter, Leah Middlebrook; and grandson, Alexander M. Djerassi.

A productive beginning

Djerassi was born in Vienna, Austria, on Oct. 29, 1923, to Samuel Djerassi, a dermatologist and specialist in sexually transmitted diseases, and Alice Friedmann, a Viennese dentist and physician. With the rising threat of the Nazi regime, in 1938 he and his mother moved to Bulgaria and eventually to the United States, arriving nearly penniless in 1939. A taxi driver in New York City cheated him and his mother out of their last few dollars.

Although he was only 16, he attended Newark Junior College and Tarkio College, and subsequently graduated summa cum laude from Kenyon College before his 19th birthday. It was at Kenyon where, in his own words, he “became a chemist.” He then moved to the University of Wisconsin, where he earned a doctorate in chemistry in 1945.

He subsequently worked as a research chemist at CIBA Pharmaceutical in New Jersey, where he developed one of the first commercial antihistamines (Pyribenzamine) and experienced the powerful connection between chemistry and human health. In 1949, at the age of 26, Djerassi became associate director of research at Syntex in Mexico City.

His research there was directed at a synthesis of cortisone from diosgenin, a molecule derived from a Mexican wild yam and a naturally abundant precursor for synthetic steroids. Later, he and his coworkers synthesized norethisterone, a potent orally available progestin analog that figured in the production of the first birth control pill, aka “the pill,” research that has since transformed science and society. Within years, the pill created significant social and economic impacts, for which Djerassi was very proud.

Djerassi reestablished his connection with academia in 1952, accepting a position as professor of chemistry at Wayne State University. In 1957, however, he returned to Syntex in Mexico City, while on leave from Wayne State, to serve as vice president of research.

In the late 1950s, William Johnson, one of Djerassi’s teachers at the University of Wisconsin, moved to Stanford University and began to recruit scientists who would transform the chemistry department into one of the best in the nation. Djerassi was one of his first appointments, joining Stanford in 1959, and became one of the pillars of the department, helping to establish a standard of excellence and enhancing its reputation over time.

Rare by even today’s standards, Djerassi published more than 1,200 scientific papers, and in doing so transformed the way chemists did their work. He made seminal contributions to the use of highly sensitive analytical tools – including mass spectrometry, magnetic circular dichroism and optical rotatory dispersion – that are critical to establishing the structure of complex molecules. In addition to synthesizing steroids, he made pioneering advances in understanding how nature makes molecules, known as biosynthesis, and elucidating the biosynthesis of marine natural products.

He and Edward Feigenbaum, a professor of computer science at Stanford, devised a computer program that predicted the structures of unknown organic compounds. This was done in 1965, at a time when most were not even aware of computers, let alone their transformative potential.

Djerassi’s incredible success, coupled with his strong personality, made him somewhat polarizing in the department, but many of his colleagues have said that he was warmer than he let on.

“He has always had a very obvious presence, and he was always ‘on.’ He enjoyed being a provocateur, and asking questions other people didn’t dare to ask, which, admittedly, could sometimes ruffle feathers,” said Paul Wender, the Francis W. Bergstrom Professor of Chemistry and professor, by courtesy, of chemical and systems biology at Stanford. “But there was another wonderful side of Carl that many people don’t appreciate, and that was his incredible generosity.”

Djerassi was instrumental in recruiting, often encouraging hires to improve the department’s diversity. Many colleagues gave examples of how this chemistry giant would show deep personal interest in their lives and their work, and made himself available to consult in both. He had a way of making people feel uniquely special. Only later would they discover that he had somehow made time in his own very busy schedule – in the last decades of his life, he was traveling 100,000 miles a year for theatrical or speaking engagements – to bestow that type of affection and interest on others as well.

“Carl offered both tremendous support and friendship to his young colleagues,” said Matthew Kanan, an assistant professor of chemistry at Stanford who knew Djerassi in his later years. “He loved to share stories – always told with an impeccable memory for detail – but he also absorbed everything you said to him and surprised you with his insights.”

A new chapter

Taking inspiration from his third wife, fellow Stanford professor and poet Diane Middlebrook, Djerassi followed his affinity for literary writing in the final 25 years of his life. As with science, this effort was far from recreational for Djerassi, and he pursued writing with a passion and discipline. In particular, he focused on integrating science with the arts, chiefly through a technique he called “science-in-fiction.”

“We have been trained to think of science and art as somehow almost irreconcilable, two antagonistic cultures,” said Arnold Rampersad, a professor emeritus of English at Stanford, at a celebration of Djerassi’s 90th birthday. “But many scientists love art of one kind or another and often know a lot about it. So for me, it isn’t altogether surprising that Professor Djerassi should have taken an interest in literature. What’s truly amazing is what he’s been able to accomplish in the field.”

Through dozens of short stories, novels and plays, Djerassi told fictional tales that describe realistic details and struggles of the day-to-day life of a scientist. In his first novel, Cantor’s Dilemma, he explored pressures that can drive a researcher to commit scientific fraud and how academia handles such a scandal.

In The Bourbaki Gambit, his second novel, he touched on the real conflicts that can arise when a group of scientists must divide credit for a major discovery. In NO, he pulled from his own experiences of commercializing a drug to illustrate the intersection of science and capitalism.

Later, he wrote plays surrounding similar topics as a way to showcase scientific dialogue. An Immaculate Misconception dealt with the science behind intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection, a type of artificial insemination, and the societal and ethical dilemmas surrounding the procedure.

“You can become an intellectual smuggler by packaging the truth in a fictional context,” Djerassi said. “If it’s exciting enough, they’ll learn something.”

He was an avid collector of paintings by modernist Paul Klee, many of which are now on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He also established the Djerassi Resident Artists Program on his ranch in Woodside, California, in 1979 as a memorial to his daughter Pamela, who was a poet and painter. The program has supported and enhanced the creativity of more than 2,000 artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty.

Plans for a memorial are being determined.

Media Contacts

Bjorn Carey, Stanford News Service: (207) 749-8698 (cell), bccarey@stanford.edu