A rare, orchestral score of Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida has become a valuable source of instruction and inspiration for Stanford scholars.

Mimi Tashiro, music bibliographer in the Stanford Libraries, with the manuscript that she secured for Stanford’s collection at a Sotheby’s auction in 2015. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

The handwritten manuscript, used in Aida’s Paris premiere in 1876, appears to be the earliest surviving copy of the famous opera’s full score – and the only surviving score from a performance conducted by Verdi – said Heather Hadlock, associate professor of music. The 1876 Paris performance featured the same singers whom Verdi had personally chosen and coached for the lead roles of Aida and her rival, Amneris, in the 1872 Milan premiere.

“This is a very special artifact,” said Hadlock, who specializes in French and Italian opera. “It’s an essential link to the opera’s original form as presented in Cairo and Milan.”

The score used during the opera’s 1871 premiere in Cairo was destroyed in a fire. No other copies of the full score used in performances across Europe and America before 1876 are yet known to researchers, Hadlock said.

Mimi Tashiro, music bibliographer in the Stanford Libraries, secured the 1876 score for Stanford’s collection at a Sotheby’s auction in 2015. Funds from the Lucie King Harris Books for Music Fund were used for the purchase.

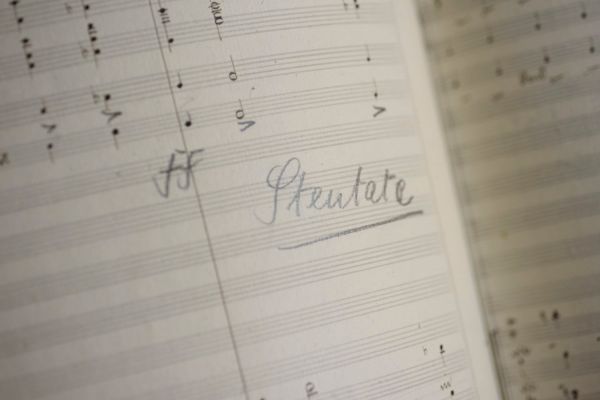

A conductor’s note on the handwritten manuscript used in the Paris premiere of Aida in 1876. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

“Full, complete scores like this are hard to find,” Tashiro said. “But we are always on the lookout for significant materials that encourage teaching and research.”

The opera tells a love story of Aida, a princess who was enslaved by the Egyptians, and Egyptian military commander Radamès, who falls in love with her. Verdi wrote the opera at the height of his career and the work was quickly picked up by theaters in Italy, America, Austria and France. To this day, Aida is considered a classic opera and is continually recreated on stages around the world.

The 1876 score, which is made up of four volumes corresponding to each of the opera’s four acts, is now available for view at the Music Library. It will later be housed in the Department of Special Collections at the Green Library.

The score’s aged, yellowish pages include many pencil markings, presumably made by the conductor or assistants preparing the performance. Some markings specify nuances of volume, phrasing and expression that add subtlety to the score. Others include lyrics scribbled along the top edges of the manuscript, possibly to help the conductor follow the stage performance while directing the orchestra, Hadlock said.

“It seems likely that some of the markings are Verdi’s,” said Hadlock, who intensively examined the manuscript with several students during a seminar class she taught in the fall.

The four volumes that make up the handwritten manuscript used in the Paris premiere of Aida in 1876. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

While the manuscript has many unique features and markings, Hadlock said she was surprised to find out that the score has only minor differences from later copies and printed editions. Operas by 19th-century Italian composers in the generations before Verdi, such as Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti, went through significant changes after their initial premieres, Hadlock said. Many of Verdi’s own operas, such as Macbeth, La Forza del Destino and Don Carlos, are notorious for their complex history of rewrites and multiple versions. Composers sometimes revised their own scores, and sometimes directors and singers imposed cuts or made changes over the years, Hadlock said.

But Verdi, who was at the peak of his fame and influence when Aida came out, evidently felt he had gotten Aida right the first time. His letters and contracts show that he exhibited strict control over the musical and theatrical form of the work.

“In the late 19th century, scores start to have this great authority,” Hadlock said. “The maestros become in control over their product,” increasing the likelihood that the Aida score we hear today is not all that different from what audiences heard over a century ago.

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu