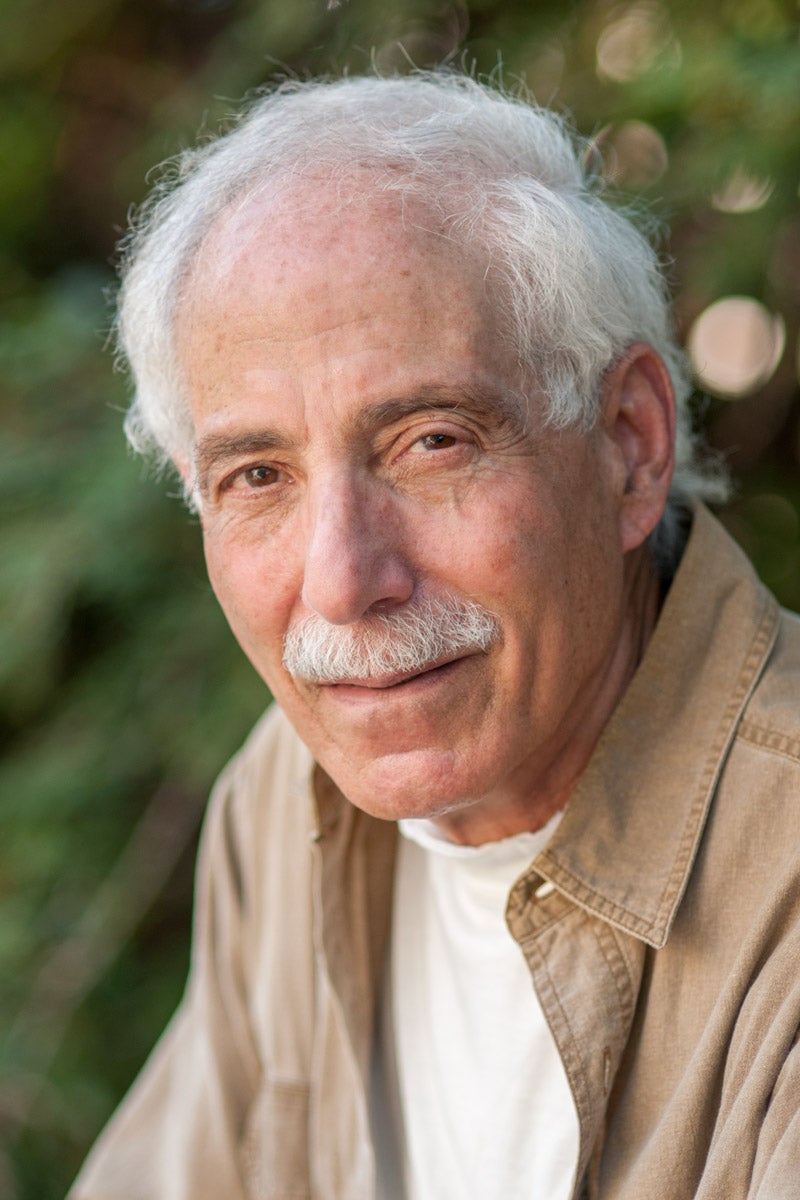

John Felstiner, 1936-2017 (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Award-winning poetry scholar and translator John Felstiner refused to stop writing until his brain failed him.

Felstiner, professor emeritus of English who taught at Stanford for almost half a century, died Feb. 24 in hospice care near Stanford from complications of aphasia, a condition that leads to a loss of ability to understand and express language. He was 80.

“Language was his life,” his wife, Mary Felstiner, said. “The meaning of words and how they sound was indispensable to him.”

Felstiner is best known for his translations and analysis of the work of German-speaking Jewish poet Paul Celan. His 1995 book, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew, was awarded the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism.

He was also recognized for his translations of famous Chilean poet Pablo Neruda in Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu, which he wrote after spending a year in Chile teaching North American poetry in the late 1960s.

Felstiner’s latest work focused on the intersection of environmental issues with poetry in his 2009 book Can Poetry Save the Earth?: A Field Guide to Nature Poems. He founded the Save the Earth Poetry Contest for high school students as part of that work, his wife said.

“The way John always came at poetry was through fascination and close attention to language, the way language moves and the way words fit together and sound,” said Albert Gelpi, professor emeritus of American literature. “He was a very distinguished translator and immensely passionate about poetry.” Among many awards, Felstiner was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Originally from Mount Vernon, New York, Felstiner graduated from Harvard College in 1958. After college, he served in the U.S. Navy for three years and then earned his doctorate at Harvard University in 1965. The same year, he came to Stanford, where he worked and lived for decades. He became an emeritus professor in 2009.

Family and colleagues described Felstiner as a passionate, hardworking man who was constantly writing and researching multiple projects.

John Felstiner’s photo from the jacket of his first book, The Lies of Art – Max Beerbohm’s Parody and Caricature, 1972. (Image credit: Martha Lowenthal)

“He was so driven and passionate about his work,” his son, Alek Felstiner, said. “He was always working on something, constantly writing and translating.”

Alek said his father’s appetite for reading books carried over to him and his sister. He said his father also loved the outdoors. The family frequently went on trips to Point Reyes, hiking trails around the San Francisco Bay Area and the lakes region in Maine.

Felstiner enjoyed teaching undergraduate students and spent some class meetings and discussions in the living room of his home at Stanford.

“He was devoted to his students and gave them as much time as he could,” Alek said.

Felstiner was also outspoken on political and international issues. He opposed the Vietnam War and tried to call attention to the oppression faced by writers in other countries, such as Chile and Russia.

“He was such a fighter,” Mary Felstiner said. “He stood up for anything that he thought should be defended. He never worried about who the opponent was.”

He also loved being involved in the community at Stanford. He helped found Stanford’s Jewish Studies program, served on the board of Hillel at Stanford and spoke up about different hot-button issues on campus.

One of the issues Felstiner took up was saving the Mayfield Playfield. When the Stanford administration proposed to build new housing on the field on Mayfield Avenue in the late 1990s, Felstiner was among residents opposing construction.

“John took hundreds of photos of students playing Frisbee, relaxing and exercising on the field,” Mary said. “He kept bugging Stanford about not destroying that beautiful place.”

In his spare time, Felstiner sang a cappella songs. He and Mary frequented music concerts and became patrons of Stanford Live performances.

While teaching a poetry class in 2012, Felstiner struggled to remember the name of Emily Dickinson, one of his favorite poets, his wife said. The primary progressive aphasia diagnosis came as a shock.

“For him, this news fell somewhere between irony and tragedy,” Mary said. “Losing words was really terrible for him. He would’ve happily lost anything but words.”

But Felstiner didn’t dwell in despair. Instead, he continued to lead an athletic life, swimming every day and running every other day on the Stanford campus. His favorite spot to jog was the Dish, his family said.

And he immediately started working on his last book, documenting his experiences as a translator of poems and literary works, his wife said.

As words began to escape him, Felstiner stacked his desk with thesauruses and dictionaries and wrote despite his condition until he finished. The book, titled Memoirs of a Maverick Translator, has not yet been published.

Felstiner is survived by his wife, Mary; his two children, Sarah Felstiner of Seattle and Alek Felstiner of New York City; and two grandchildren, Asa Felstiner and Brayden Puchtler.

Donations in Felstiner’s memory can be made to the Sempervirens Fund or the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment.